Big-picture trends from 2023 in games, and unsustainable emissions trajectories

Every year Newzoo puts out a report on the major trends happening in the global games market. If there was one central finding of this year’s report, which covers what happened to games in 2023 (which I first saw summarised in Simon Carless’ newsletter), it’s that the games that are finding the most sustained success are getting older and older (same). This means new games are not taking the place of many existing ones, presumably because something about them is fundamentally providing the experience that these players want.

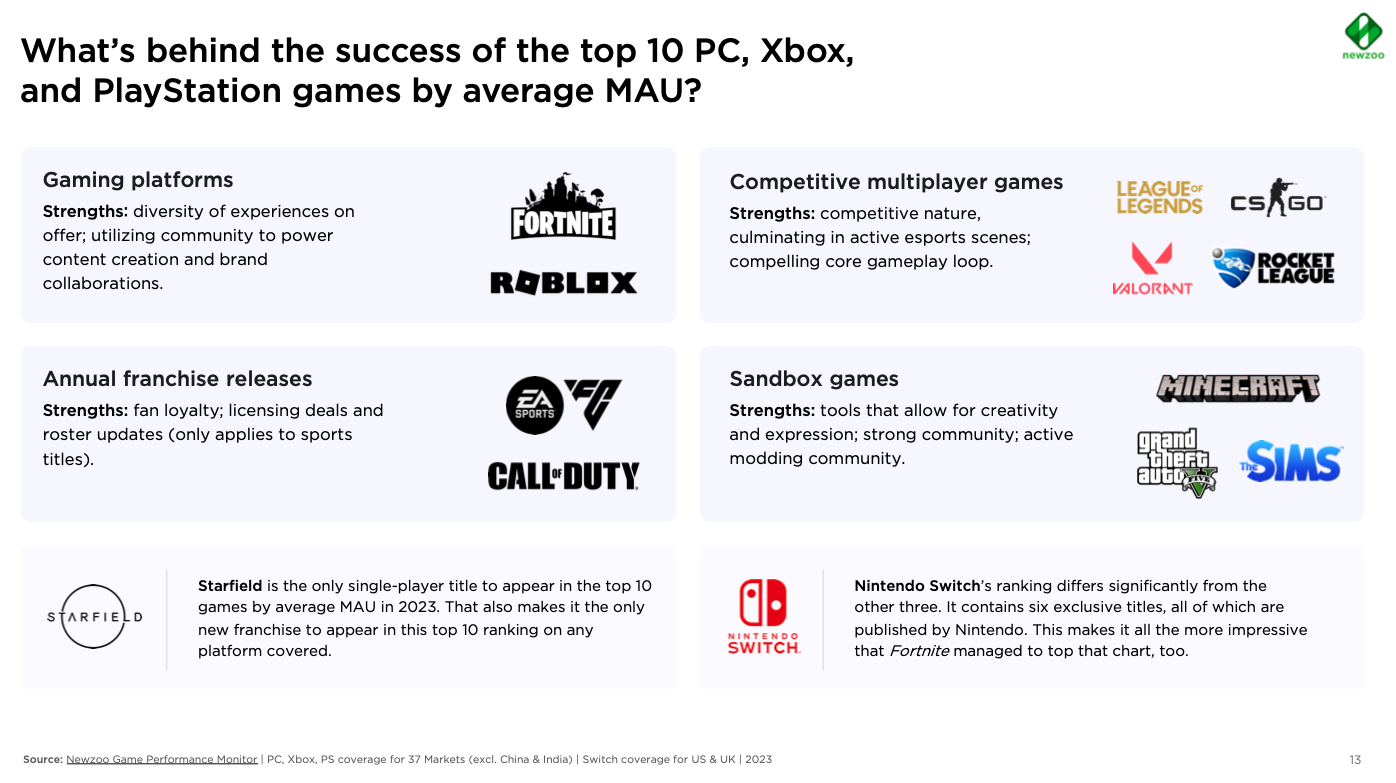

Here’s how Newzoo describes the characteristics of the top 10 games for monthly active users. These are the games capturing the majority of player attention and engagement, and they are increasingly Gaming Platforms (Fortnite, Roblox), Competitive Multiplayer (League of Legends, CS:GO, Valorant, Rocket League), Sandbox Games (Minecraft, GTAV, The Sims), and Annual Franchises (Call of Duty, EA Sports). In other words, barring one or two exceptions, these are complex, largely online games which require vast infrastructure beyond the players own hardware. As the report notes, the only (!!) single-player game to appear in the top 10 in 2023 was Bethesda’s Starfield.

Without directly measuring and modelling the impacts of these trends, an almost impossible task given the patchwork, haphazard, and dare I say non-standarised way that game companies report their emissions, it’s risky to draw conclusions about the impact of these trends on greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s worth trying.

While there are all sorts of difficult implications from the dominance of these “older games” (especially for those in the business of actually making and selling new ones!), as Carless points out, a new report from the French Think Tank The Shift Project gives us an approach to thinking about this with. The report provides some hugely applicable guide-rails about what these huge macro-trends might mean for the future of the games industry and its global carbon impact.

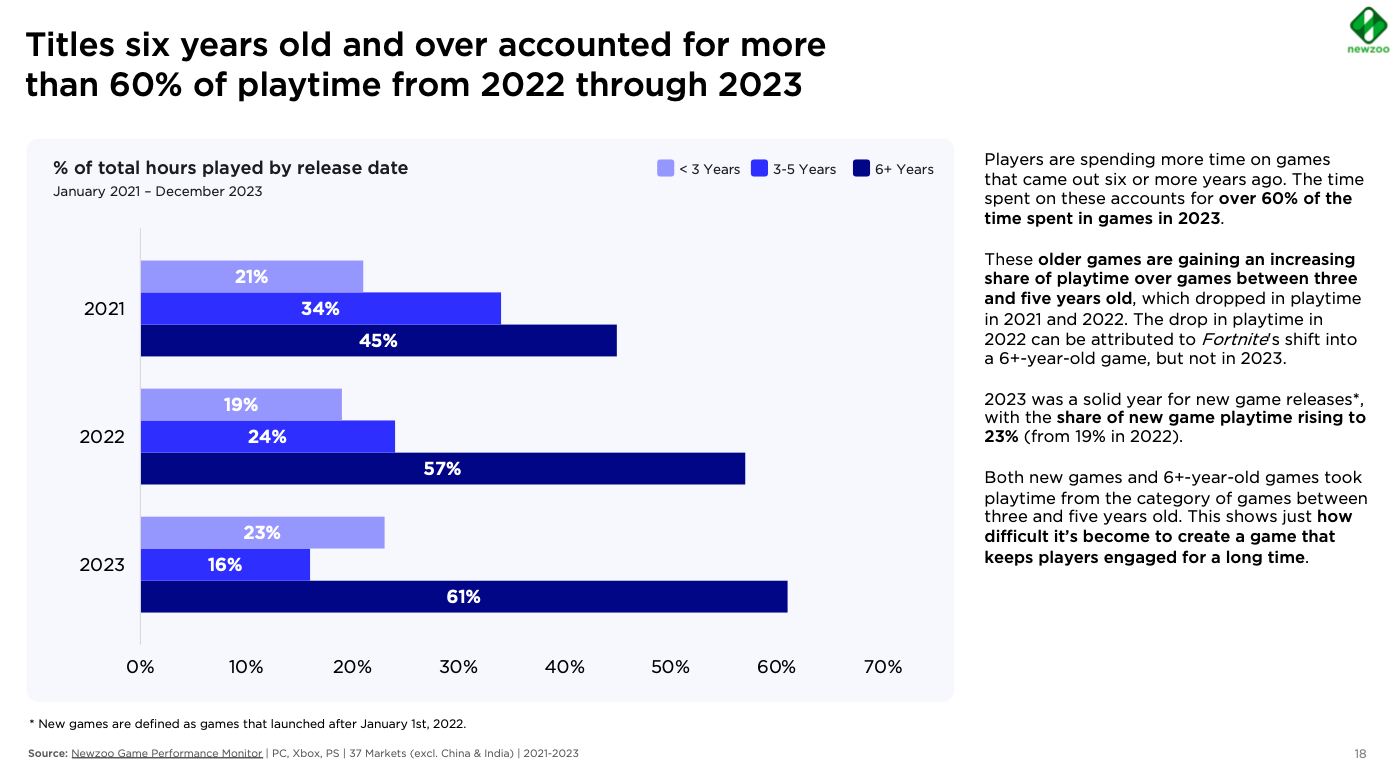

Let’s start by seeing in more detail what exactly the Newzoo report is saying. Here’s their breakdown of the % of total hours played by release date – the distribution of playtime across new (<3 year old), middle-age (3-5 year old), and mature (6+ year old) games. The audience for new release games seems pretty stable, not changing much for the past three years. The major change, however, is in the increase in playtime for games 6+ years or older, coming at the expense of games in that “middle age” bracket of 3-5 years old. New games are not “sticking around” or holding onto audiences for as long as they used to.

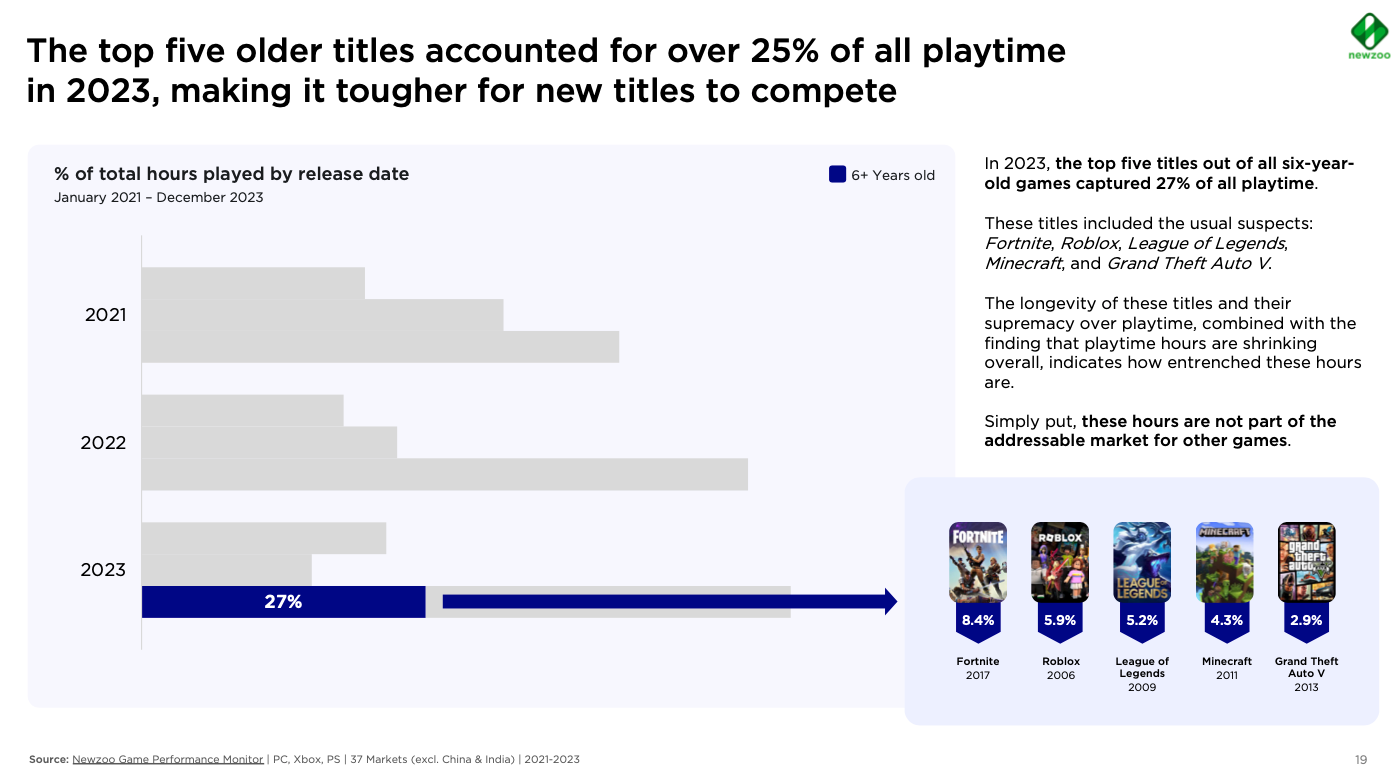

Newzoo drills down into the mature games bracket and shows us that it’s dominated by a number of older games – Fortnite, Roblox, League, Minecraft and GTAV make up 27% of the total playtime for 6+ year old games. That’s five mega-popular games accounting for a whopping 16% of the entire games market’s playtime!

Each of these games is primarily played online, requiring extensive infrastructure to support, and their scale might give us some pause. The amount of back-end server and communications infrastructure involved in online gaming is a huge question mark hanging over the industry, with many of the companies that make these games themselves having only partial or limited visibility over this huge (and probably growing?) aspect of gaming.

So the platformization of games is increasing, with a large chunk of players choosing to play one or other of these very mature game ecosystems. Without knowing what the alternative games are that players are eschewing, it’s difficult to say if this shift is necessarily a net negative from an emissions standpoint – if they’re all moving away from graphics intense new-release blockbusters at 4K with Raytracing there’s a world in which that could produce less emissions. But the reverse is just as likely, as the drift from single-player offline games to online platforms and games-as-a-service enrols entire new technical systems, servers, data centres, metrics and data collection, with these having serious effects on energy required per hour of gameplay.

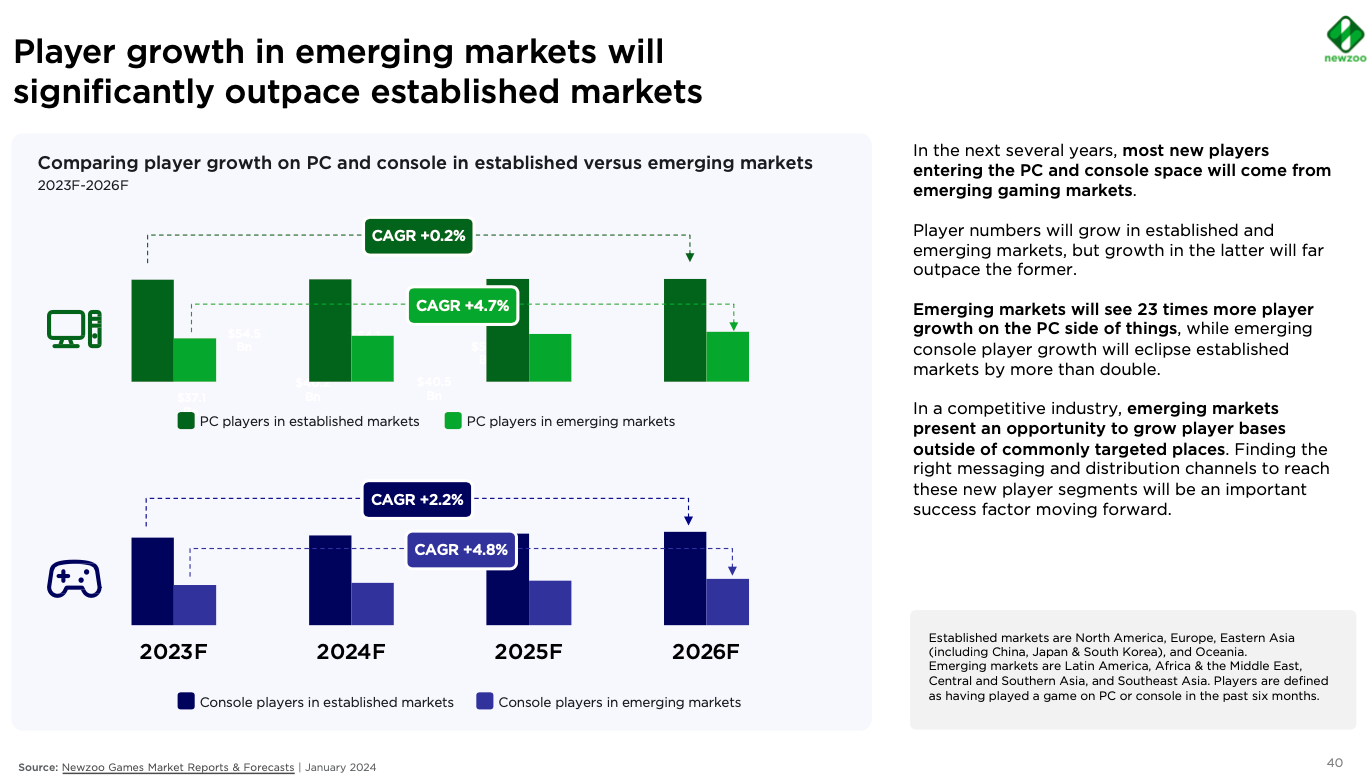

There’s another potential shift that comes out in the report, which is also going to be key to the long term sustainability of the industry, and this is where players are in the world. The report points towards the increasing growth in gamers in so-called “emerging” market countries. The one area that Newzoo see opportunities for substantial growth is in these so-called emerging markets. To back up the potential of this strategy and the importance of players in these countries, they point to a potential for “23 times more players growth” on PC. (I have no window on their methodology for forecasting that prediction so I’m just going to take it at face value)

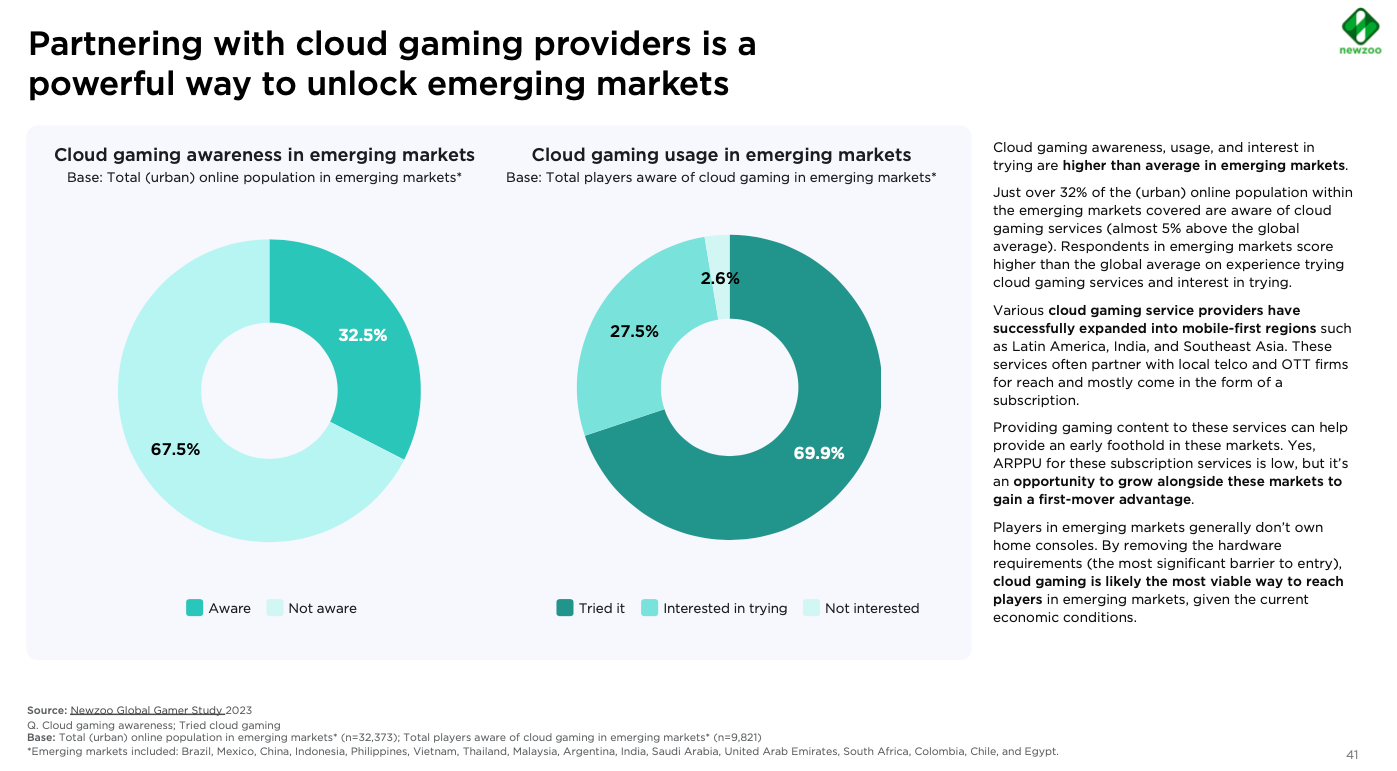

In particular they call out cloud gaming as a potential growth area for these regions, where the price of hardware like consoles, PCs, etc is often prohibitive, but where mobile phone penetration is already quite high. They suggest that “cloud gaming is likely the most viable way to reach players in emerging markets”. Both of these observations seem quite reasonable.

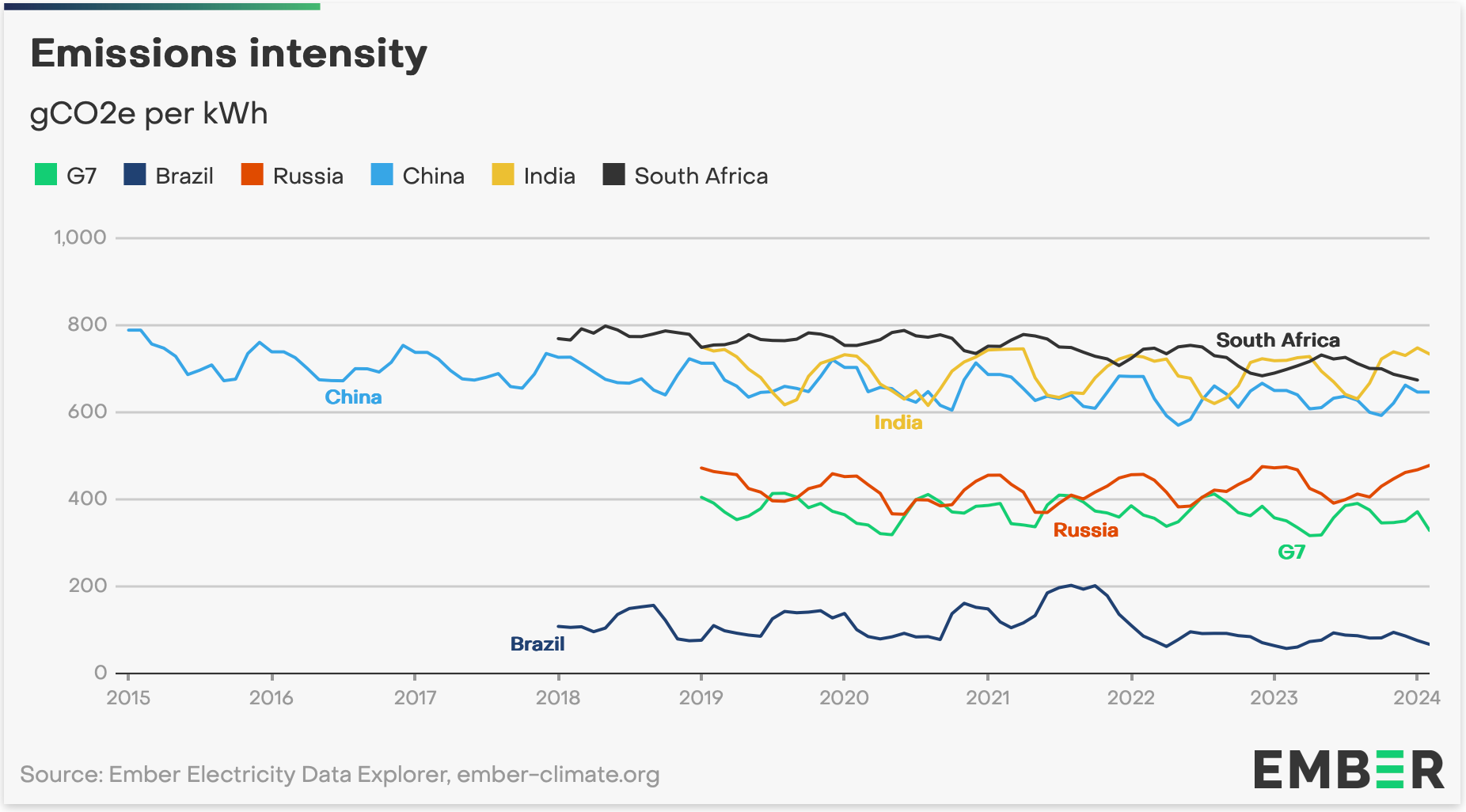

The obvious consequence of this growth, however, would be higher emissions within the boundaries of these emerging market countries as energy demand for edge-computing, mobile network infrastructure and client devices increase. This is a problem because of the on-average higher emissions intensity of power systems in emerging market countries.

Here’s a comparison of the recent power intensity of G7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States) vs the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa).

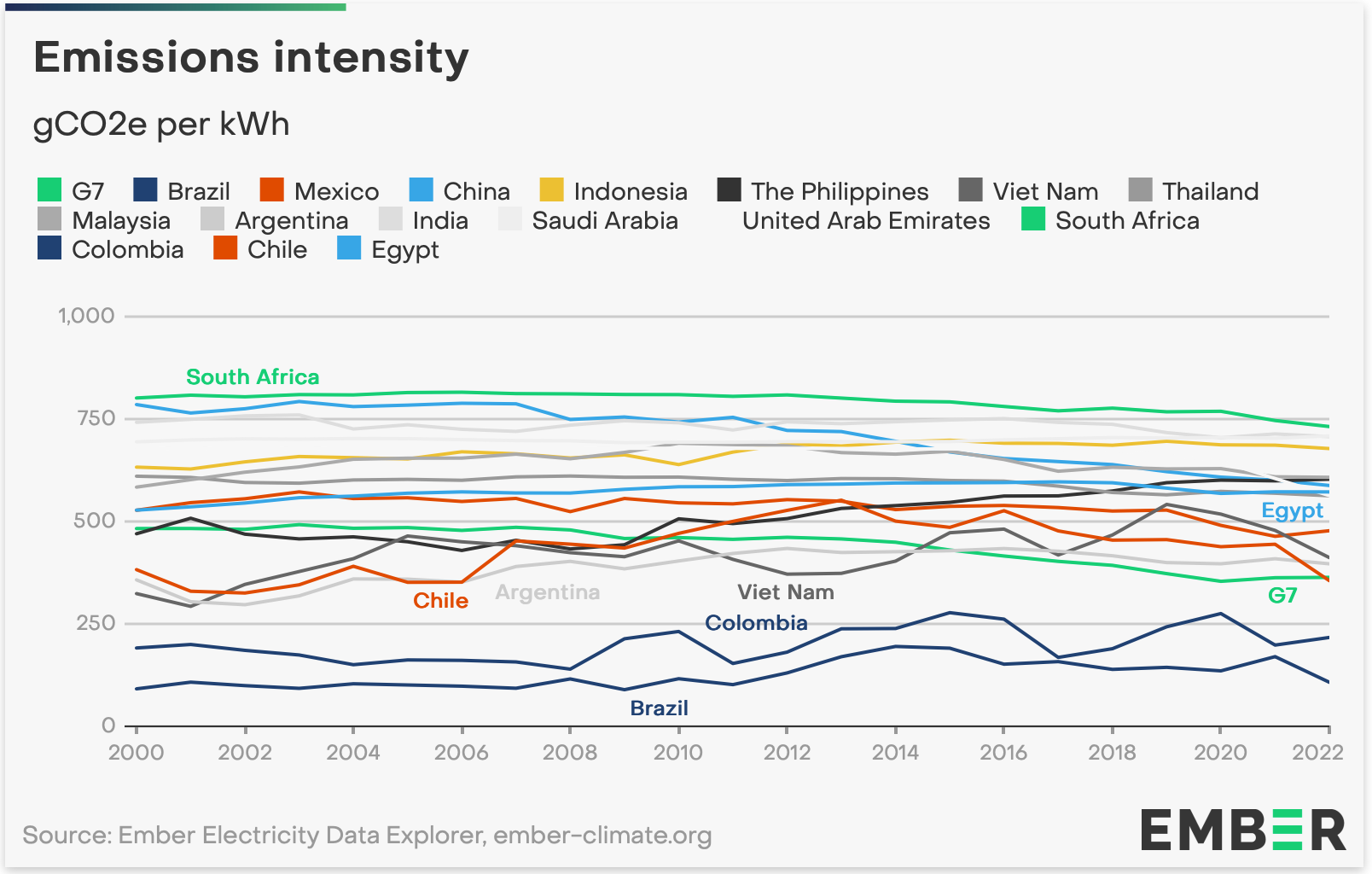

And to be even more accurate in matching the Newzoo predictions, when we look at the CO2 intensity of power in each of the countries specifically considered as "emerging" – only Brazil and Colombia, with access to plenty of hydroelectricity, are typically lower than the G7 average. All the rest of the other countries have the same or higher emissions intensity power systems.

Would growth of players in the above countries result in higher emissions? If much of the growth in players comes from cloud gaming, requiring more data centre infrastructure, perhaps yes? If matters a great deal how these users play – mobile and Switch gaming is far more efficient than PC. But data centres are often built where access to cheap renewable power is most available, so it’s difficult to say. Howeverany growth where power grid emissions are high is going to increase the average end-user (or gamer) intensity on an hourly basis.

The obvious element missing entirely from this analysis, of course, is the crucial question of equity and climate justice. So-called emerging market countries have historically done the least to contribute to the current concentration of CO2 emissions in the atmosphere. Players in these countries by all rights deserve higher standards of living which, I would argue, includes improved access to the sorts of complex and fulfilling gaming experiences we have come to take for granted in the West.

The conclusion we should probably draw, then, is that we have an obligation in the rest of the industry to “make room” within games’ global carbon budget for these other countries and their players, redoubling our focus on energy efficiency and emissions reductions in the “core” of the games industry.

But so far this is all just minimally-informed speculation based on some very crude assumptions of what might be arising from these big-picture trends. What would be really informative would be if someone had actually modelled these changes. That’s pretty much what The Shift project have done in their latest reports, published both in French (as Mondes virtuels & réseaux face à la double contrainte carbone) and English (Virtual worlds and networks facing the dual carbon constraints).

There’s actually two reports and a couple of summaries, but I think the full report is worth your time engaging with. The two reports are about mobile network development on the one hand, and the attendant power consumption as 5G+ networks roll-out (which is the one I have not read), and the other is about the increasing deployment of "metaverse" style virtual worlds, VR & AR tech across existing and emerging sectors could mean for emissions. The latter is the one I have dug into, and I suspect a few readers might be interested in it too.

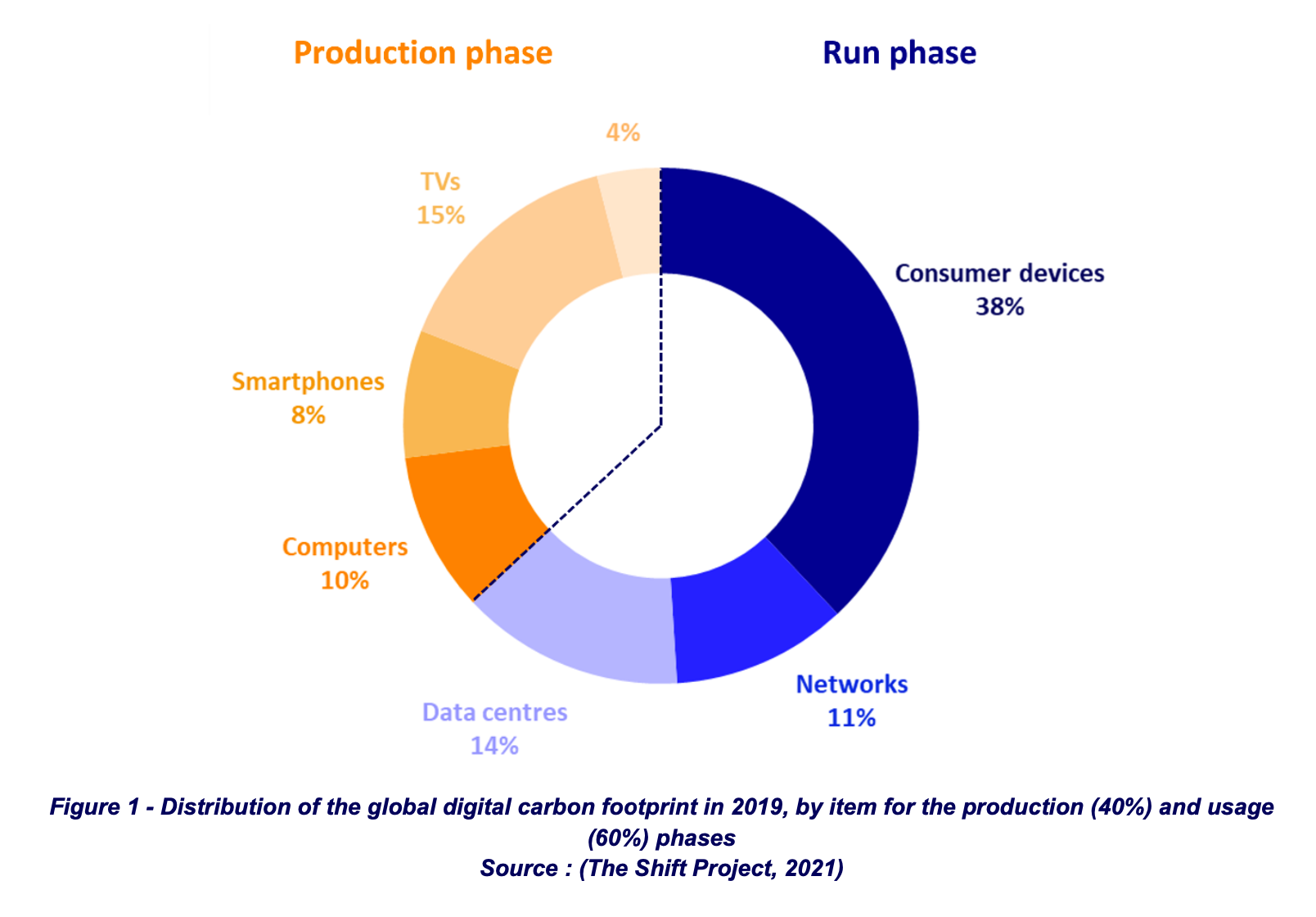

The report builds on The Shift Project’s previous work estimating the global carbon footprint of the entire digital sector, broken down into the segments shown below – the left hand side (in yellow/orange) are embedded emissions from producing new devices, the right hand side is energy consumed by devices, as well as by the infrastructure they rely on. I’m not intimately familiar with the methodology behind these figures, but I know that the International Energy Agency (IEA) has used the Shift Project’s previous studies in its own modelling, so there’s good chance they’re legit.

The report begins with a preamble about the scale of the digital/IT sector’s global emissions and the observation that “Technical and operational optimisations are unable to offset the sustained growth in infrastructures, [stocks and flows]".

This sober approach is already far bolder than much of what you will find in mainstream Anglo-sphere discourses around IT sector emissions. There, sustainability strategy tends to continue to rest upon the assumption of ability to access enough renewable electricity to continue to meet the growing demands for power in this sector. Already we are starting to see that assumption stretched if not break down, as Ketan Joshi pointed out on LinkedIn recently, noting the issue in Google’s annual disclosures: “even though Google is genuinely a leader in procuring high-quality power purchase agreements for clean energy, that isn't sufficient to keep up with their very significant increase in power demand over the years.”

The Shift Report starts out by challenging the current trajectory of IT energy system growth, a critical intervention in these debates:

Making the digital sector compatible with the dual carbon constraint therefore involves not accelerating the optimisation levers already deployed, but putting it on a fundamentally different trajectory to the one it is currently following. In the same way as other sectors of the economy, it must achieve its decarbonisation target, which industry players (GSMA, GeSI) have set themselves through the SBTi initiative and on the basis of an ITU recommendation (SBTi et al., 2020, p. 9) of -45% by 2030 compared with 2020 at global.

With that as the stated goal, why the interest in virtual worlds? Well, because major tech sector actors like Meta and others have committed to them, under the umbrella of the “Metaverse” and related ideas for expanding their markets:

The announcement of massive investments in the metaverse in 2021 (Facebook, 2021; L’Usine Digitale, 2021) and the enthusiasm at national and European levels for immersive technologies (Basdevant A., François C., Ronfard R., 2022; Direction Générale des Entreprises, 2022; European Commission, 2023) raise questions. Virtual worlds offer new uses for a digital system already undergoing the test of energy and climate constraints as a whole. The simple case of immersive technologies suggests that the energy footprints of the three components of the digital system (devices, data centre, network infrastructure) are destined to move together in unsustainable directions.

The rest of the report is expressly devoted to figuring out how, where, why, and in what direction we should expect the energy footprints of devices, data centres, and network infrastructure to travel.

The report does this by taking a hugely innovative approach to the problem. Firstly, it acknowledges that the metaverse vision is already not a coherent one, involving multiple actors, products, competing technologies and platforms, and so on:

The resulting blurred, multiple, and heterogeneous vision not only makes environmental assessment complex but also complicates the refutability (in the epistemological sense) of statements such as "the metaverse is compatible with the Paris Agreement". In the absence of a clear definition of the concrete object "metaverse" or "virtual worlds", consideration of its implications may lead only to relativistic debates on the potential services that the metaverse could provide, or on the types of metaverse that would be less emissive than others. Such an approach would eliminate the questioning of the role of virtual worlds in a sustainable digital environment that aligns with the dual carbon constraint.

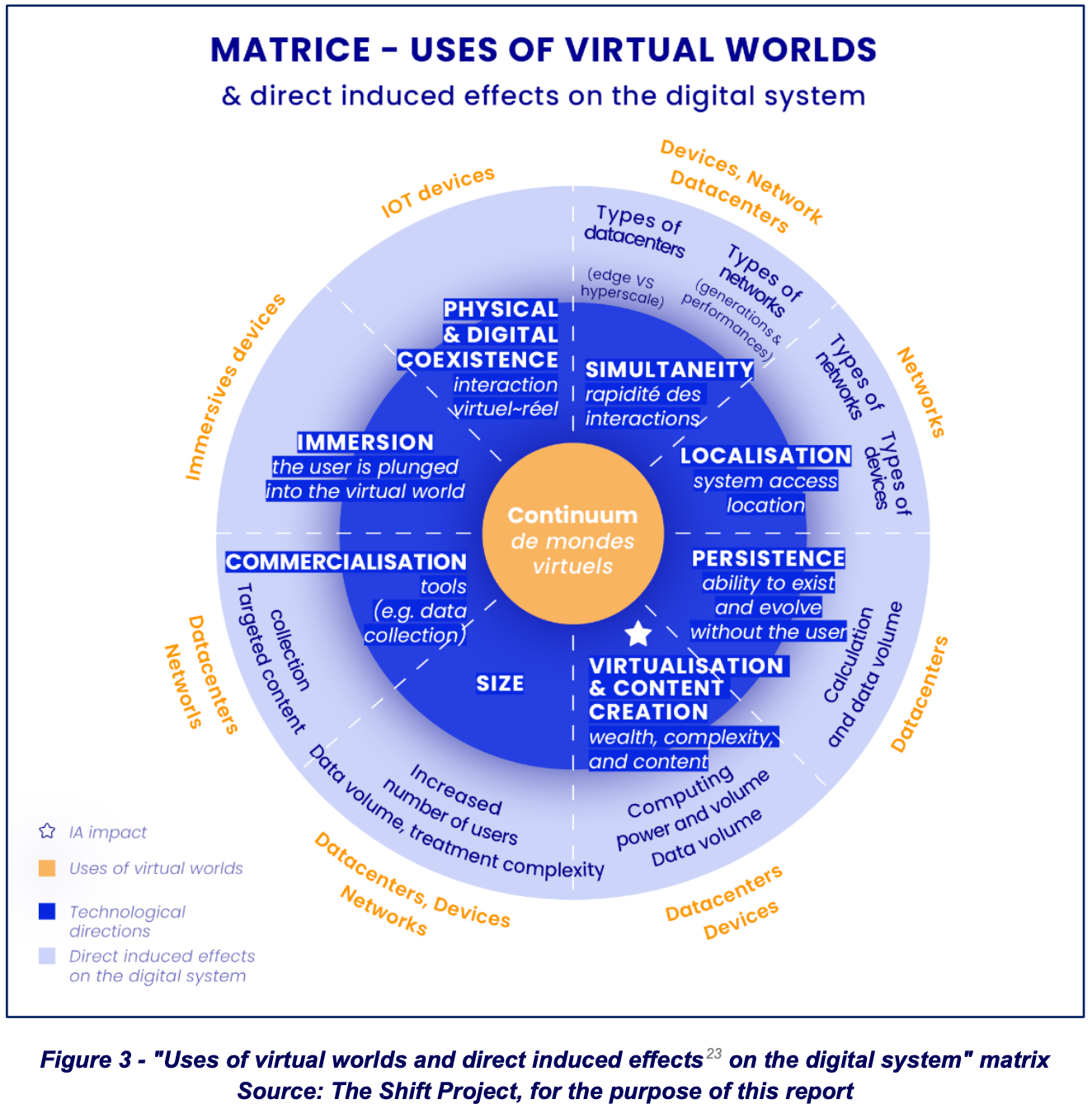

It is precisely to avoid this pitfall that The Shift Project is proposing a double definition, both based on technological characteristics and on use cases. The aim is to provide the best possible overview of the continuum of virtual worlds and describe their energy and climate implications. It also aims to, based on the specific technological directions chosen, identify the relevance conditions of virtual world modalities by considering them within their deployment and usage context.

So the Shift Project is interested in the “technological direction” (i.e. more/less/different) “metaverse” type solutions might head in, helpfully referring to these technologies as a “continuum of virtual worlds”. Combining these general tendencies or trajectories with analyses of specific (proposed and extant) “use cases” builds up a picture of the deployment of this nebulous mix of technologies and ideas which, (as I think will become clear) are in near lock-step with the observed trend towards “Games as platform” seen in the Newzoo 2023 report.

The Shift Report identifies six use cases, not intended to be exhaustive but rather which “aims to reflect a diversity of virtual world uses from a technological and material perspective”. The uses cases are:

- Immersive online conferences and meetings

- Video games and social worlds

- Online shopping

- Cultural experiences

- Digital twins

- Pornography

Remember the goal here it to understand the direction of technological travel, rather than to necessarily map out all possibilities for so-called “metaverse”, or virtual worlds. To the use cases above they add the following characteristics of virtual world technologies which any individual technology, platform, or product might instantiate, or aspire to:

- Physical and digital coexistence

- Immersion

- Simultaneity

- Localism

- Persistence

- Virtualisation and content creation

- Commercialisation

- Size

The purpose is to “link these characteristics to material content (devices and infrastructures)” considered alongside whether or not that particular characteristic or feature is essential, useful, or optional “to the functioning of the virtual world.” Conveniently, a major focus is Fortnite, about which they observe the following:

- The vectors of physical and digital coexistence and immersion are relatively standard (a smartphone, a console, a computer, a screen);

- Gaming requires fast operations and therefore simultaneity;

- The smartphone gaming option offers a new type of localisation, making it suitable for mobile use (not without impact for mobile access networks with the video streams that need to be transmitted);

- Depending on the gaming options, the environment is not persistent, but the avatar (the player's profile) is persistent in the sense that the statistics collected will be used to improve the gaming experience;

- In terms of virtualisation, rendering the universe as a whole and the avatars' interactions with it calls for a set of calculations;

- The gaming experience and commercialisation involve data collection of around 5 PB per month in order to improve the player experience (Amazon Web Services, 2018);

- Fortnite keeps its size in check with gaming options that are tailored to its size (sandbox in several sectors, battle royale with a finite number of players), particularly for its large number of users (8 million at the same time). Fortnite also organises events designed to bring together all its users (125 million). What's more, it is widely adopted (over 200 million users and 350 million subscribers), making it all the more popular (Amazon Web Services, 2018).

Once they’ve been through this process with each of the use cases and characteristics, they end up with a matrix that “integrate technological development choices into a systemic, infrastructural, and long-term dimension, in order to link them to the resulting energy dynamics.” In other words, we see who is going to want to use more power, more devices, for which sorts of end products and services, and why. Here’s their diagram of that matrix.

Working from the centre out, we move from the entire continuum of virtual worlds, to the characteristics that lead to a certain technological direction (e.g. immersion), and their associated “induced effects” (“increased number of users, data volume, treatment complexity”), with the uses these get put to and the practical actors involved (“Datacenters”, “Networks”, etc) on the outer layer.

The conclusions from this exercise, at least the ones most relevant to games, are the following:

- The immersion axis influences the volume of immersive devices as well as their carbon footprint and unit consumption;

- The virtualisation and content creation axis could lead to the installation of new servers or the establishment of new data centres to enable richer content, just as the persistence axis ensures the continuity of the virtual world's service even without the user's device power consumption;

- The combination of the two axes, virtualisation & content creation and immersion, impacts the embedded carbon footprint and power consumption of immersive devices, which then become increasingly powerful to enable more realistic rendering (with perhaps more moderate impacts on data centres and networks) or by leading to the installation of more powerful and numerous servers (with more significant network impacts but lighter devices);

- Combining the commercialisation axis with the immersion axis could result in the collection of new types of data (geolocation marketing, emotional marketing, optimisation of the gaming experience), which would result in higher data rates and therefore effects on the networks: instantaneous, with an increase in the variable energy consumption of the networks, but also longer-term, leading to capacity deployment or even new generations dedicated to meeting this specification.

- The simultaneity axis can lead specifically to an increase in edge computing, to bring computing, storage, and data processing capacities as close as possible to the user;

But all these are only possibilities: “The effects induced on the digital system depend on the intensity with which the technological directions are pursued.” The analytic approach The Shift Project lays out is broader than existing product-based analyses that might compare the demand impact of, say, a new game or feature, and is also “broader than the eco-design perimeter of a virtual world”. It’s a truly systemic view, and the truly visionary among the industry will find the tools here to grapple with the pressing sustainability questions we are all facing. If we are going to keep the energy and emissions consumption of games in check, we are going to need to think carefully about the designs of our products and services.

So should game leadership, and ESG team leads, be taking up this report and the tools it provides? I would say so. As the authors note, “by describing the collective and infrastructural energy and climate consequences of digital offerings, this matrix serves as a valuable tool for engaging in collective discussions among players and stakeholders regarding the specifications of future offerings.” But how do we do this work collectively? How do we make sure it happens in a way that is not just siloed inside individual companies? Perhaps we need, some sort of external organisation, a network, something that can facilitate these discussions… some sort of… sustainable games alliance?

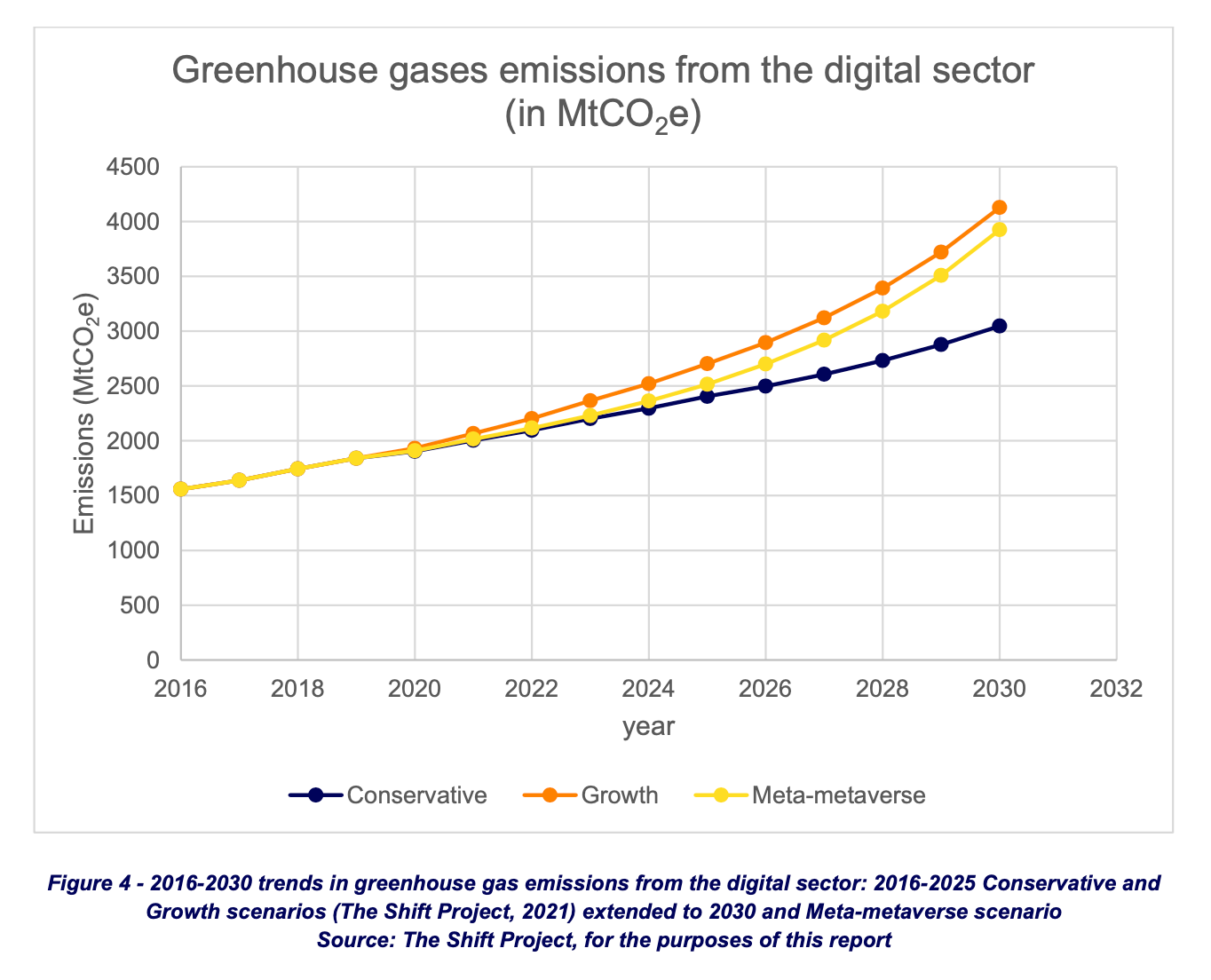

What are the most likely pathways for IT sector emissions then, given the potential expansion into metaverse/virtual world type solutions – the continued expansion of the Robloxes and Fortnites, perhaps even their integration into other platforms? The Shift Project has three reference scenarios that could result from the interplay of all these tendencies and technologies, with some pretty spooky numbers for overall emissions.

Both Conservative and Growth scenarios extend existing Shift Project report trajectories, and the new Meta-metaverse scenario sees the rapid expansion of virtual worlds, falling somewhere between the two. On the simple metric of raw emissions numbers, if the IT sector adopts metaverse style technologies, the impacts may be less than some worst-case scenarios (the growth trajectory) but far more than conservative ideal:

In this projection, the carbon footprint of the world's digital economy moves away from the "Conservative" scenario towards the dynamics of the "Growth" scenario, and the carbon footprint of the digital economy reaches 3.9 GtCO2e in 2030, or 7% of global emissions.

The conclusion is that,

an undifferentiated deployment and widespread adoption of virtual worlds has the effect of putting the digital realm on an unsustainable trajectory, incompatible with the Paris Agreement.

The key element here being the undifferentiated deployment of virtual worlds. With smart analysis and considered work, taking the time to understand the big systemic implications of the design and implementation of our virtual worlds from Fortnite to FarmVille perhaps we can avoid locking in this sort of growth. But left to its own devices, this seems unlikely – a shift in thinking and working is needed.

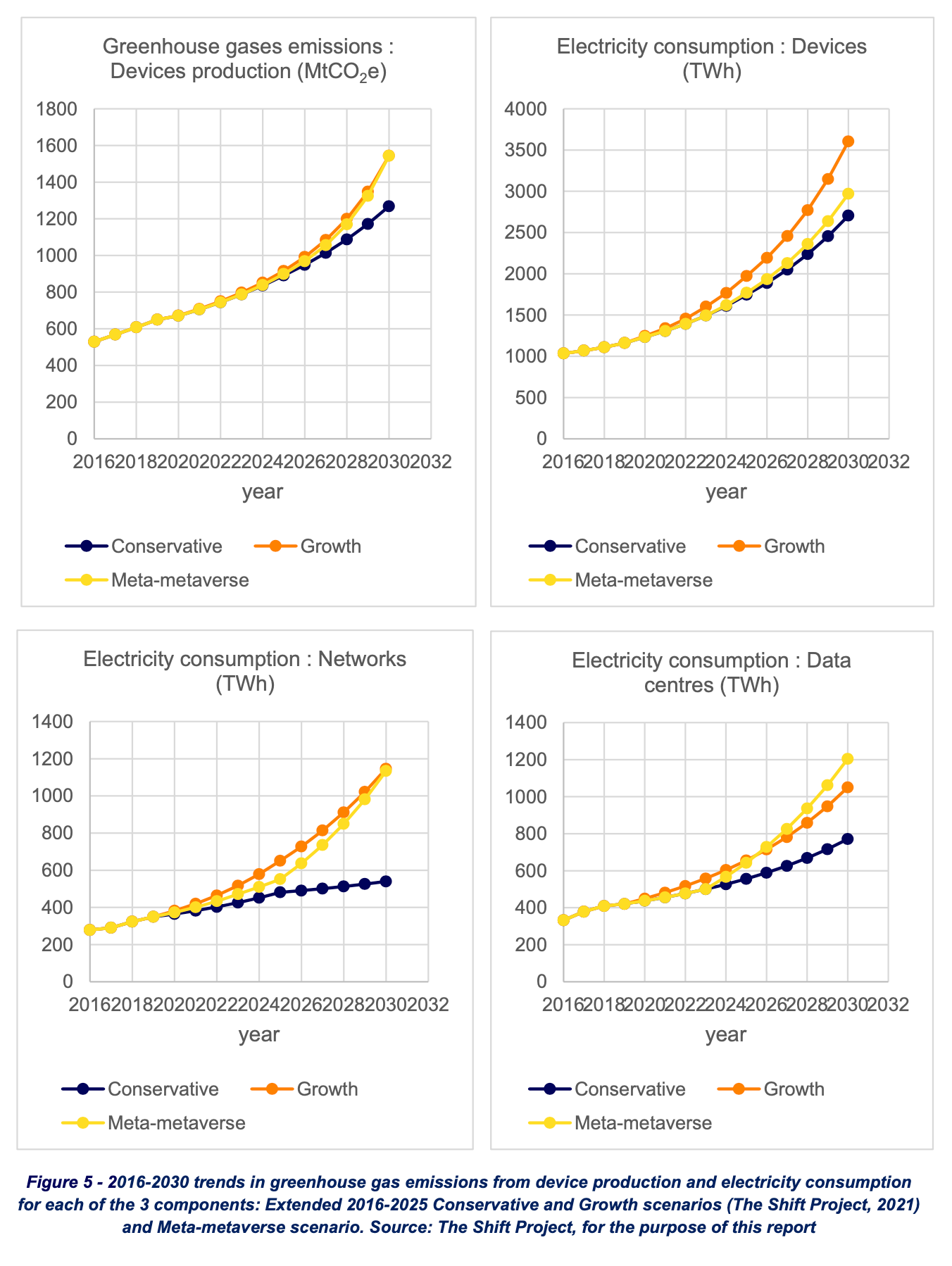

There’s more interesting graphs in the report about the expected demand/growth in energy from devices, networks, data centres as well as in device manufacturing across these three scenarios. Interestingly, the production phase emissions (i.e. from making VR headsets, consoles and GPUs) in a metaverse style scenario end up being higher than in current growth scenarios (or perhaps the same? its hard to read).

The report goes on to apply the framework for thinking through when and how metaconferencing (i.e. virtual reality meetings or conferencing) could be considered “sustainable in terms of energy and climate impacts, and under what conditions it should be encouraged or discouraged from this point of view.” I won’t go into the details here, because it’s several pages long, but they find through their analysis a demonstration “that substituting metaconferencing for videoconferencing in the workplace increases energy consumption and direct and induced (first order) emissions on the digital system.” However the analysis doesn’t address indirect effects, like avoiding flights so “from an energy-climate perspective, it is [still] necessary to identify if there are conditions under which the substitution of metaconferencing usage for carbon-intensive mobility usage, for example, would result in a net reduction in indirect emissions.” They instead suggest that individual companies are well placed to consider how it might work to shift “in-person meetings or interactions to remote ones, even though video conferencing is already an option.” Maybe VR meetings are more fun than Zoom? Would GDC being held in VR be enough to convince people not to fly?

So what can we say then? What types of virtual worlds or metaverses might be sustainable, and in which conditions? Here are the reports authors final conclusions which are unable to be categorical, but which nevertheless I find deeply relevant and a very welcome call for attention to detail and difference:

Since endorsing the undifferentiated deployment of virtual worlds leads to a climatic impasse, it needs to be differentiated.

To achieve this, we need to study the net energy and climate contributions of possible uses for virtual worlds. This depends both on the technological choices made at the design stage, and on the context in which they are deployed.

For each virtual world modality, we therefore need a systematic and exhaustive methodological and quantified assessment of energy and environmental costs (including adoption and usage assumptions).

Coming back to the Newzoo big-picture shifts identified in the report on 2023, it’s still not precisely possible to say what effect the domination of older games-as-a-platform is having. But now, at least, we have a method laid out for finding some of those answers. The Shift Project report gives those in charge of developing and directing these products new ways to generate insight into the climatic effects of their decision-making.

But before we see that, we still would need to see leadership at Epic Games and Roblox (in particular!) and others besides. These mega-platform games still have yuet to take on board the challenge of adapting their business strategy and growth to the demands of a 1.5ºC warming scenario. By doing this they would join a growing number of corporate leaders from Microsoft and many other that have seen which way the wind is blowing, and can see for themseles how dangerous and detrimental a true global climate breakdown would be for digital businesses.

Thanks for sticking around and reading a very long piece. I hope it gave you some food for thought.

If you enjoyed it please consider sharing it with someone else who you think might need to hear this message of (what the French would call) digital sobriety.