Climate is economics is political economy is climate

I’m back, at last. I had a thing planned to write here over the last few weeks, but the main findings were “non-conclusive”, so I haven’t written them up.

Instead, I wanted to express some slightly vague ideas and gesture at some big challenges that are constantly on my mind at the moment. This was prompted by a really interesting conversation I had this week with CNET journalist David Lumb (excerpts of which may or may not make it into the chapter he’s writing for an edited collection).

Maybe about ten years ago now (give or take) I decided I had to take more of an interest in economics – I think this was around when Yanis Varoufakis started talking about the political-economic situation he faced as the new Greek Finance minister in the Syriza government in 2015, but it had been growing for a while. I had read the late, great David Graebers Debt: The First 5,000 Years and had the same experience as many others during the Occupy Wall Street moment, where the scales fell from my eyes and I understood that there is nothing apolitical about money and debt. I also had, of course, bought a copy of Marx’s Capital Vol.1 as a PhD student around the same time – though I never made much headway until later – and gleaned from it and other secondary texts a basic understanding of the labour theory of value and some other key ideas. Unlike Graeber’s approachable prose, I found others’ summaries and syntheses of Marx’s Capital more graspable (including a really fantastic graphic novel-style illustrated version which I lent to someone, now sadly forgotten who). Capital is not the sort of book you get the most out of by reading alone, either, by all accounts it’s best read in community and conversation with others, but it still remains an exceptional book, and utterly vital.

But it was Varoufakis anyway, who loudly and clearly expressed (to anyone willing to listen!) the politically murderous consequences of the refusal of the European Central Bank to refinance Greek government debt. The so-called “troika” – the German Chancellor (then Angela Merkel), the German Finance minister (Wolfgang Schäuble), and the ECB – stubbornly refused to engage in any sort of negotiations over debt restructuring that would actually help the Greek government service its debts – instead deploying the moral position of debt absolutism: that “one must repay one’s debts”, a position which Graeber so comprehensively dismantled in his book. Debts are written off and written down all the time as part of normal negotiations – being a creditor carries a certain amount of risk, after all, and if it didn’t what possible reason would there be for the creditor to receive any sort of return? All they are providing is money. The fact that Greek debt would not be reduced or restructured was transparently a flexing of the power of northern European creditors, the signing of a writ of execution for any sort of prosperous future for the people of Greece who were not to blame for their government’s mismanagement or the poor performance of its economy.

So it was witnessing from afar the very obviously spelled-out injustice that the unelected troika was imposing, via the internecine economic mechanisms of modern monetary warfare, a crushing austerity for the Greek population that made me acknowledge that if I want to understand the world, and why things are the way they are, and what the possibilities are for the future, then I had to better understand economics. It is just too important to remain ignorant of. It was Varoufakis, whom I first encountered through his work with Valve on the Team Fortress 2 hat economy, that helped make incredibly clear, via his trademark moral clarity, the importance of this idea of political economy – the broad term that roughly describes the nexus of economic decisions and their political and practical consequences.

It’s not a coincidence that so much of our present can also be traced back to that moment too: the rise of the fascist Golden Dawn under Greek austerity was enabled and turbo-charged by the ability to blame the crisis on a huge and visible wave of migrants from the Syrian civil war, becoming the blueprint for a general fascist strategy around the world. The same imposition of antidemocratic and antisocial austerity has been repeated time and time again this past decade. Most recently the still-young Starmer govt in UK is repeating the same stupid mistakes. The same suppression of democratic interest in favour of the narrow, sectional demands of monied interest has played out over and over, with examples almost too numerous to count.

In our conversation this week, David asked me specifically about sustainability reporting done by games journalists, how important I thought it was, and whether I had any hope for it improving – particularly in the context of the near collapse of games media more broadly. I do think it’s important, but I think journalism is facing a double crisis. Yes, there is the economic crisis of the collapse of profitability and the shrinking of newsrooms all over – with the concentration of ad-selling power in the hands of Google/Meta etc. – but there’s also a narrative crisis in the West as well.

In his acceptance speech for the 2024 Weston International Award, journalist Pankaj Mishra looked back even earlier than 2015, to point to the origins of the crisis in journalism. Describing the effects of the post-9/11 “War on Terror” liberal consensus and its warping effect on the public.

Today, the war on terror is widely accepted as a military and geopolitical failure. But it is still not fully understood as a massive intellectual and moral fiasco: an attempt by the Western media as well as the political class to forge reality itself, which failed catastrophically, but not without embedding cruelty and mendacity deep and enduringly in public life.

Even before that catastrophic failure, though, the seeds were present waiting to germinate. The failure of Western narratives to reckon with the defining political movements of the 20th Century – decolonisation and the liberation of racially oppressed peoples around the world – was once a key ideological blind-spot, a pre-requisite to being considered a legitimate part of the media. But now it presents a massive liability:

One could read millions of words on the merits of Western democracy and liberalism and the evils of Eastern totalitarianism by such intellectual luminaries of Anglo-America as Michael Ignatieff, Timothy Garton Ash, Martin Amis, Thomas Friedman, and Anne Applebaum without encountering a paragraph on the consequences of slavery, imperialism, and decolonization. They seemed fixated with the crimes of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, but these so-called liberal internationalists barely manifested any awareness of the modern Western history of mass bondage, colonial dispossession, and genocidal wars against indigenous peoples.

Such ignorance, an affordable luxury once, would be fatal today for a younger generation of journalists and commentators: they confront a global order where democracy and liberalism, or even ordinary political stability, are no longer a given. They are required to see the world as it is, without the cold war imperative to prettify one’s own side. They are in one sense forced to accurately chart our fragmented geopolitical and cultural landscape, and to recognize its multiple histories and geographies and newly emerging constellation of forces.

This assessment rings deeply true to me, and it’s one I’ve bene struggling to express. I really encourage you to go read his full remarks, they are historically informed, and illuminating.

So these two dimensions then – the exercise of economic power, and the exercise of an overriding narrative power – are not separate, but united symptoms of modern global capitalism. And I think it’s critical for those of us who want to understand our global climate future that we have a grasp on, and can name the problem, the blockers, the barriers quite precisely.

Jason Hickel, one of the world’s foremost researchers of degrowth and the political economics of climate change, gave a talk recently, that touches on many of the same things. The key part is from about 1:50, but I recommend watching the whole thing.

Hickel's description of the paradox is spot on. The paradox is that the world has never been more rich, society has never been more technologically capable, and never been more specialised and organised in our entire history… and yet when we look at whether or not that capacity has been harnessed for the most essential task of preserving the safety of life and the planet itself what do we see? Clearly we are failing at this task.

We're in this incredible Paradox where the world economy we know is just massively productive like our productive capacities are incredible. Think of the scale of the labor that humanity has as at its disposal, the resources, the technology, the factories, the energy, the materials. Incredible amounts of production to the point of breaking past ecological limits and yet the vast majority of the human population lives in conditions of massive deprivation. 80% of the population can't meet basic needs.

So what explains this incredible Paradox? It's ultimately our system of production. The social and ecological crisis that we face, which appears unresolvable, is ultimately a symptom of our system of production – capitalism. Where our productive capacities, our incredible productive capacities are organized overwhelmingly around what is most profitable to Capital, and what can most facilitate accumulation in the core – rather than what is obviously necessary to meet human needs and achieve our ecological objectives. So we're in this wild place we're just like oh solving poverty is just going to take Generations. …The climate crisis: who can figure out how to solve this? It seems intractable. None of this is true, it's lies. These are problems that can be very easily solved and very quickly. The problem is that we don't have control over our own productive capacities, because we don't have an economic democracy.

I find this an extremely compelling analysis, deeply motivating and encouraging, but also sobering. We live at the richest point in history – the wealth and technology across the world have never been more substantial, and yet neither have we ever been closer to the complete annihilation of the ecological basis for our entire way of life. Why? Because of capitalist power.

This same systemic analysis, once you understand the fundamental drive of capitalist accumulation (capital goes in search of labour to purchase and extract a surplus from by owning the productive processes, and in turn increasing into more capital – or as Marx puts it much more evocatively: “Capital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”) and add on top of that a tiny sprinkling of further specific understanding around things like the nature of private equity, asset price inflation, etc etc. I think we get a very clear understanding of where things are headed, and a bit more of a sense of what we need to do to change it.

It’s no wonder that the games industry is struggling to turn a profit and so costs through massive layoffs. The source of its entire business model is the disposable income of consumers, which has been crushed by a growing class of billionaires, thanks to massive inequality and the concentration of wealth at the top. Since Western countries pursued neoliberal tax cuts that benefit the rich, pursued policies that encourage asset price inflation, and stopped redistribution of the most wealthy through taxation well of course there is less money to go around.

Another idea that I’ve come across recently, and which I desperately want to make more time to read about, is the idea of “foundational economy”. This seems to be that different parts of the economy operate according to different logics, and some server more “foundational” roles in enabling life:

It argues against the idea of a unitary economy where all activity is or should be subject to one logic and set of principles, Instead, “the economy” is divided into zones, each one with different principles, ways of working and objectives. Politicians obsess with the tradeable sector and focus “industrial policy” on this relatively small sector, aiming to improve competitivity especially in glamorous, high tech new industries. But, for ordinary citizens, what matters more is the foundational economy. This is the large, neglected and sheltered zone of the economy which employs around 40% of the workforce and provides households with basic goods and services like healthcare, education, utilities and food.

I quite like the way they describe how the analysis resists simple categorisation onto the left/right political spectrum:

Those who are concerned to pigeonhole new ideas often ask where foundational economy stands on the left/right continuum which they understand as a preference for state or market. This framing of the choice is not sensible when financialised capitalism brings us not the market but monopoly with platform capitalism and outsourcing conglomerates feeding off the state. … As Amartya Sen argued, development should enable citizens to live the lives they have reason to value (not to meet a set of needs we define for them or to expand market output and improve competitiveness).

The idea that monopoly markets and sclerotic states are both failures to deliver on conditions for a good life is deeply appealing to me – maybe it is to you too? I strongly suspect that a central challenge for anyone wishing to create a world of genuine sustainability is going to be achieving this realignment of the vast breadth of human potential we call “the economy” towards something that delivers the lives most people actually want to live. Slower lives, with less work, less stress, and – yes – less consumption.

It’s also going to mean grappling with the incompatibility of endless wars and a global military complex that is extremely profitable, extremely adept at dishing out violence, and extremely influential on largely captive political leaders. Earlier this year I watched a video on the greenhouse gas emissions of the world’s militaries, which remains shrouded in secrecy.

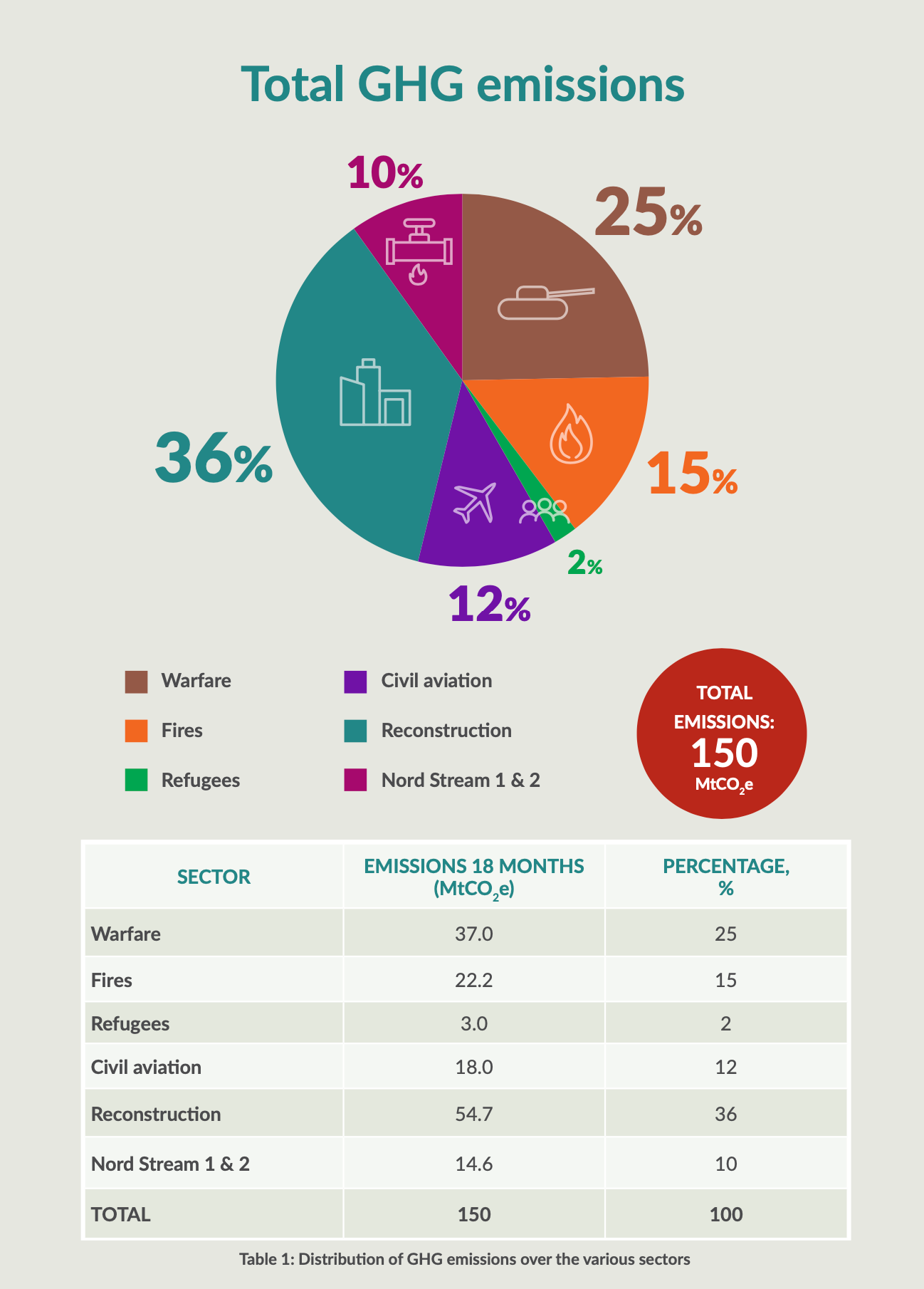

One of the reports referenced in the video estimated the climate cost of the Russian invasion of Ukraine – finding that the largest climate impact was not even from military operations, but rather from the future cost of rebuilding so much of Ukraine. 36% of a total 150 million tonnes of CO2! For comparison, that’s about equivalent to about 3x the annual games industry emissions.

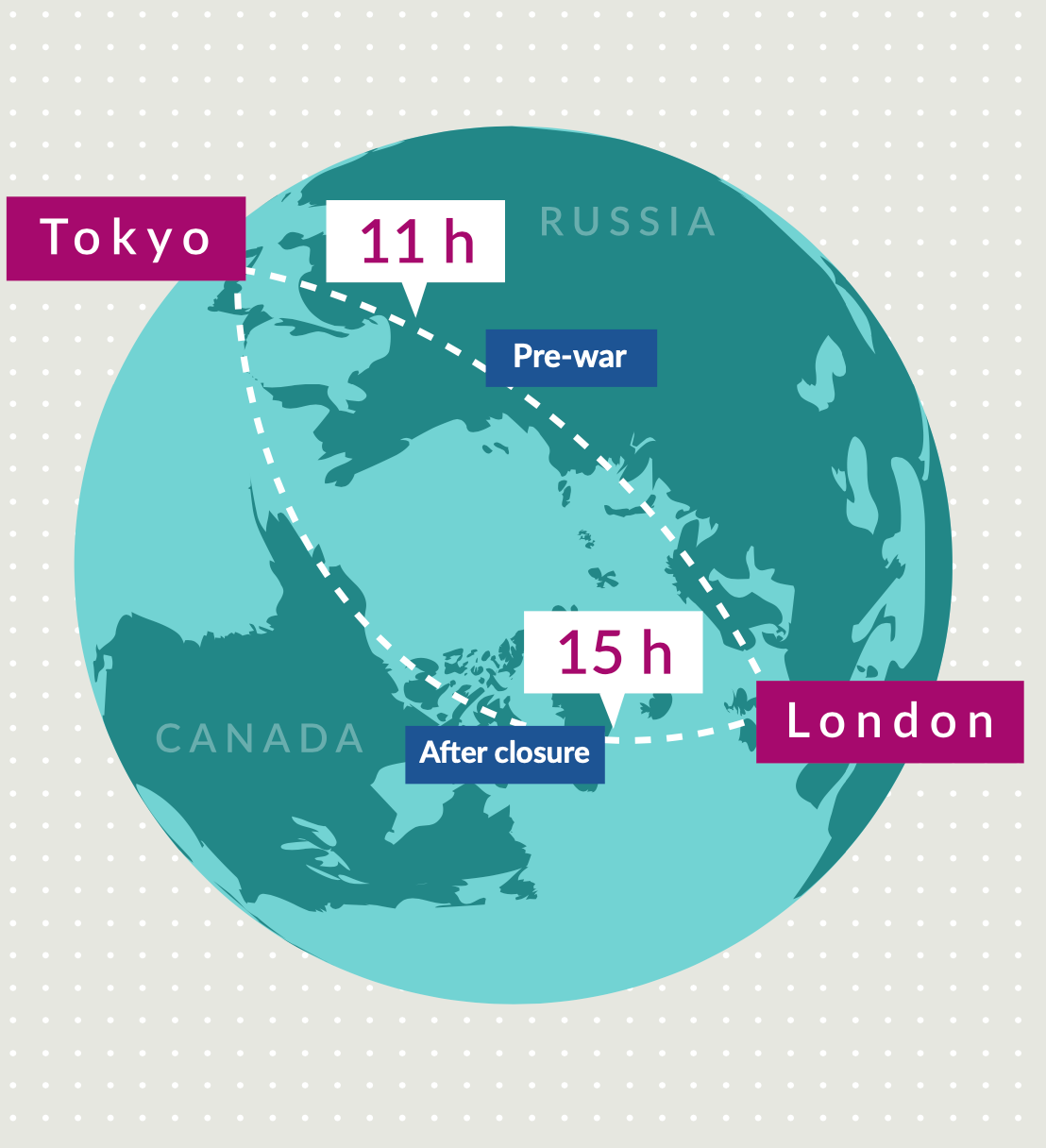

12% of that total comes from a completely unexpected source as well – the redirecting of commercial flights around Russian airspace, extending travel time in the air. Weird unexpected risks and consequences abound.

The other report estimates global military footprints, putting figures on their day-to-day “operational” emissions. Extrapolating from the headcount of the largest militaries, and applying multipliers for supply-chain emissions based on various piecemeal disclosures and estimates, it concludes that:

our best estimate for the military’s operational GHG emissions is 500 MtCO2e – 1.0% of global GHGs – and for the global carbon footprint, it is 2,750 MtCO2e – 5.5% of the global total.

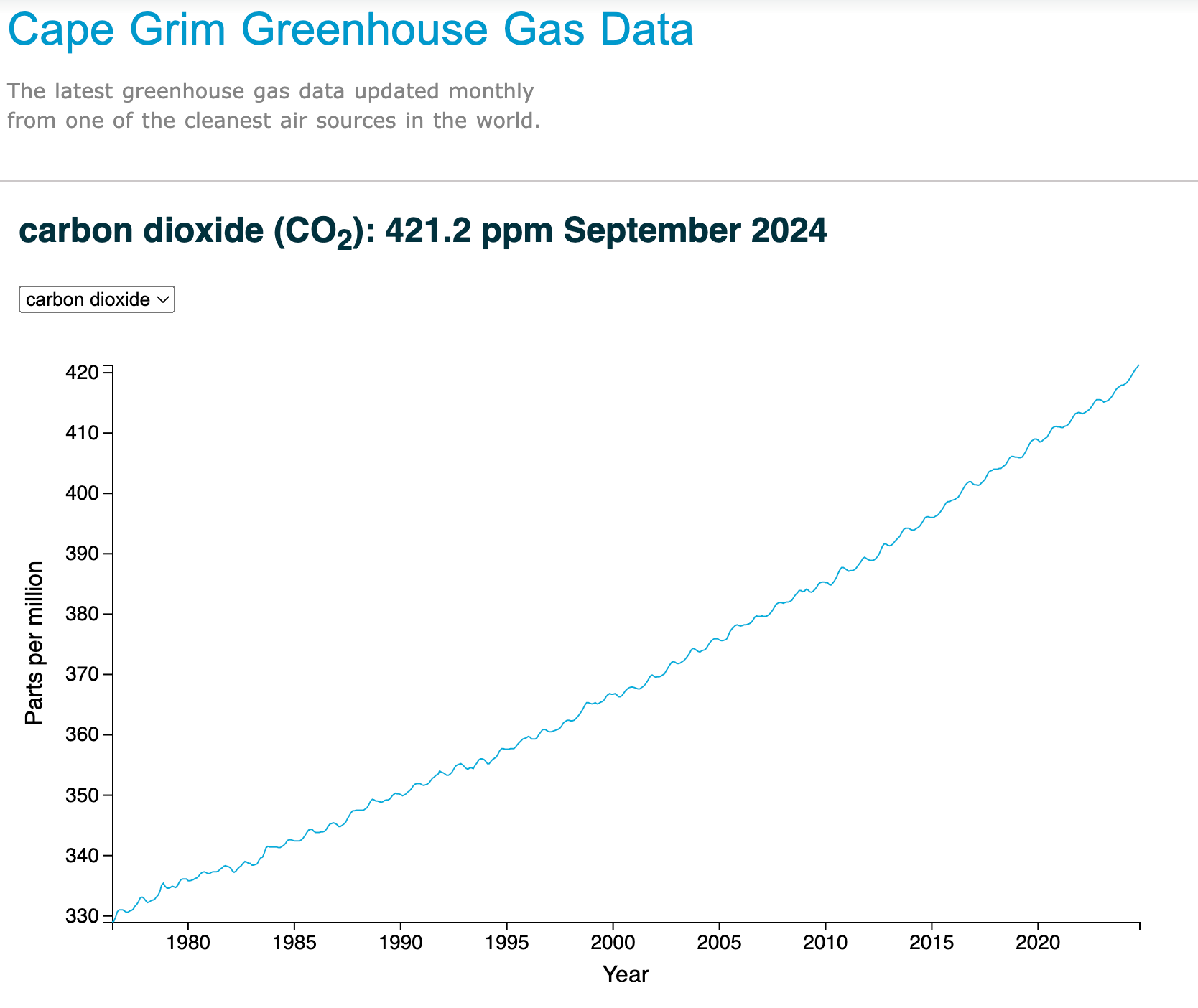

If the climate crisis has taught us anything it’s that we share this planet, the same atmosphere. There is nowhere to go to entirely escape the effects of climate change, and CO2 concentrations at the most remote places on Earth follow the same global trajectory as everywhere else. Our fates are entwined. Everything we do happens on the same planet. Both the global climate struggle and the highly globalised games industry are subject to the same (massive) forces. It’s important to know about, and to figure out how to use that knowledge to guide our actions.

I don’t really have a conclusion for this one – just to say that is the stuff I’ve been thinking about lately, struggling with while trying not to get too buried in the (important) details and minutia of working on the SGA GHG emissions standard. The principles and ideals we want to see in the world really matter, and should be a guide for us.

I’ve had a lot less free time to write for GTG lately, so I might need to scale back my ambition a bit. The weekly cadence isn’t quite working anymore, and I would be a bit of a hypocrite if I sacrificed personal sustainability for it. Please adjust expectations accordingly. Thanks, as always, for reading Greening the Games Industry.