Markets vs mayhem ...or How we choose to govern the climate crisis really, really matters: on the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)

I think it’s safe to say that the Western world is experiencing a crisis of public governance. Electoral democracy is no longer representing the ‘demos’, captured instead by lobbyists, a widespread disillusionment at the lack of responsiveness of major parties with their traditional social bases hollowed out, and a pervading “antipolitics” mood afflicting many of the advanced economies. Not unrelated, the dominant neoliberal political-economic mode of governance which has held sway since before I was born was finally killed by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and yet somehow lurches on zombie-like without a real alternative or replacement. Bidenomics in the US and the turn to Green industrial policy in Europe don’t count. As Daniella Gabor has argued, the modern green state is obsessed with ‘derisking’: “achieving public policy priorities by tinkering with risk/returns on private investments in sovereign bonds, currency, social infrastructure.”

These questions of governance and legitimacy don’t exist in a sphere separate from the climate crisis either. Narrowing in on climate governance, two top-level frameworks govern (most of, though not all) the world’s approach to emissions reductions. The Paris Agreement aims to keep warming “well below” 2ºC and ideally below 1.5ºC, with countries setting their targets and timelines, the Agreement is largely agnostic about the political-economic methods countries should employ to get there, and how long it takes to reach zero emissions. This has been the cause of some criticism, as it matters a great deal whether we get there in a just way or an inequitable way, and whether we turn the emissions tap down more towards the start of the end. This is a weakness of a “net zero” goal without plans for immediate reductions in the here and now. A quick reduction is essential, and that’s why the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) – the other top-level framework and increasingly the de facto standard for corporate governance of the transition – requires not just a net zero target date, but interim targets as well. Progress can’t be deferred to a decade from now, it’s urgent.

All of this context is necessary to understand my feelings about the EU’s flagship sustainability disclosure rules – the European Sustainability Reporting Standards – the governance system that now sets the benchmarks for sustainability disclosure across the EU for the foreseeable future. Having spent weeks deep in the bowels of the ESRS, having now expended a non-trivial portion of my life trying to wrap my head around this bit of delegated legislation, I can only really describe my feelings as “extremely mixed”. They run the gamut from frustration and bewilderment to resignation and disappointment with regular contact. What on earth were they thinking?

The ESRS is like a labyrinth. If your materiality assessment process determines you may have impacts in every possible category (5 different environmental ones, 4 different social ones, and 1 for corporate governance) and you decide to provide all the information any investor or ESG-minded stakeholder could ask for, including all the optional recommended disclosures, then you have got yourself over one thousand data points you are having to collect sustainability data for, understand, and narrate in a meaningful way.

Just like all good labyrinths, a beast sleeps at the heart of it. The beast that’s ready to catch us out I’ve started to think of as “prerequisites”. This is not an official part of the ESRS, but it’s the implied missing piece between what’s asked of disclosure preparers, and the raw list of what data points are required. Let me illustrate, with a couple of examples.

To help businesses meet their regulatory obligations, the Union funds the “European Financial Reporting Advisory Group” or EFRAG. EFRAG has been producing a series of documents with non-legally binding “implementation guidance” that aim to convey both the spirit and the essence of what is required by the ESRS. Just like the rest of us, however, even the technical sages at EFRAG, however, cannot avoid their best bit of guidance simply coming in the form of a big old spreadsheet. The third of these implementation guidance documents (IG 3) is a list of all the “data points” in the different ESRS sections.

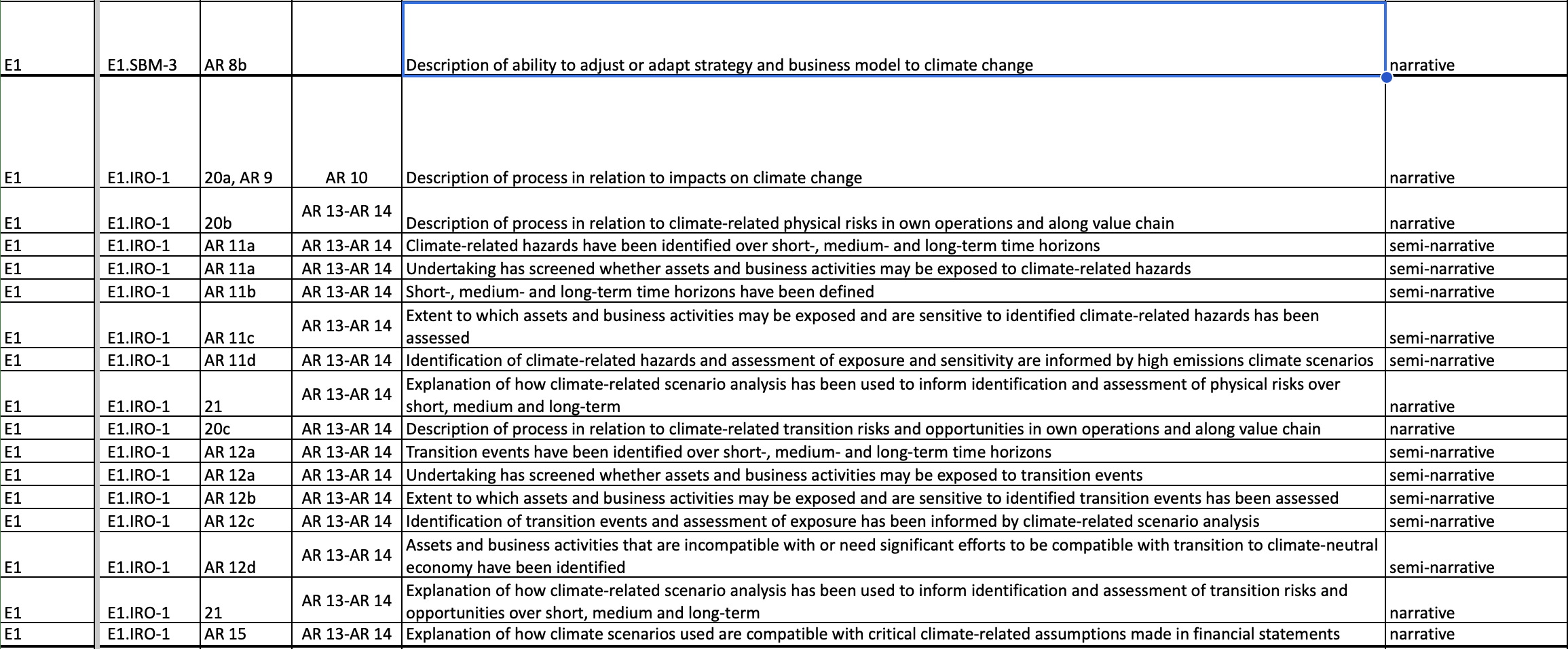

Here is a screenshot of just seventeen of the 200+ data points required in the first of the five Environmental sections: “ESRS E1 Climate Change”.

Let’s talk through how to read it and what it’s asking for. The leftmost column confirms that, yes, we are in the E1 “Climate Change” part of disclosures. The next column shows that we are moving on from the section E1.SBM “Strategy and Business Model” section of disclosures, which for this data point (in column 5) asks disclosers to narrate the ability of their organisation to “adjust or adapt strategy and business model to climate change”. So far so good.

But how does one describe a game business’ ability to adjust or adapt to climate change? This is not asking for a generic statement about any games business and its ability to adapt, it’s about your games business and its sustainability context and perspective, so surely before you could write that, you’d need to know about the nature of your own business, your exposure to climate risks, and have some sense of what a shifting climate means both physically (more floods, fires, storms, droughts, power outages, disruptions, etc) as well as politically and economically (from new taxes to fund green initiatives, greater consumer scrutiny of corporate claims, missed opportunities to save money through lowering energy costs, and so on). This is not the sort of thing you can leave till the day before it’s due. Having a list of all the things that are expected in an ESRS-compliant disclosure is no guarantee of being ready and prepared to make them. And there are literally hundreds of them.

Not all of the data points are quite so demanding as that. Some of the examples directly below that first line are closer to “yes/no” answers – “Undertaking has screened whether assets and business activities may be exposed to climate-related hazards”, is one that could be answered affirmatively. But then again, you’d also want to make sure you provided a bit more detail about how you did this process, because when your third-party auditor comes along to perform their assurances that you’ve done your job, they’re going to want to see your working. This is not a system that operates on trust.

This is backed up by returning to the EFRAG spreadsheet. The two other columns on the left that I haven’t mentioned yet add more detail about the expectations in a given disclosure. The third column in the screenshot says which paragraph in the actual text of the ESRS you can look up to find the requirement in its legal form, but the fourth column also notes which “Application Requirements” (AR) must be considered when forming your disclosure for a given data point.

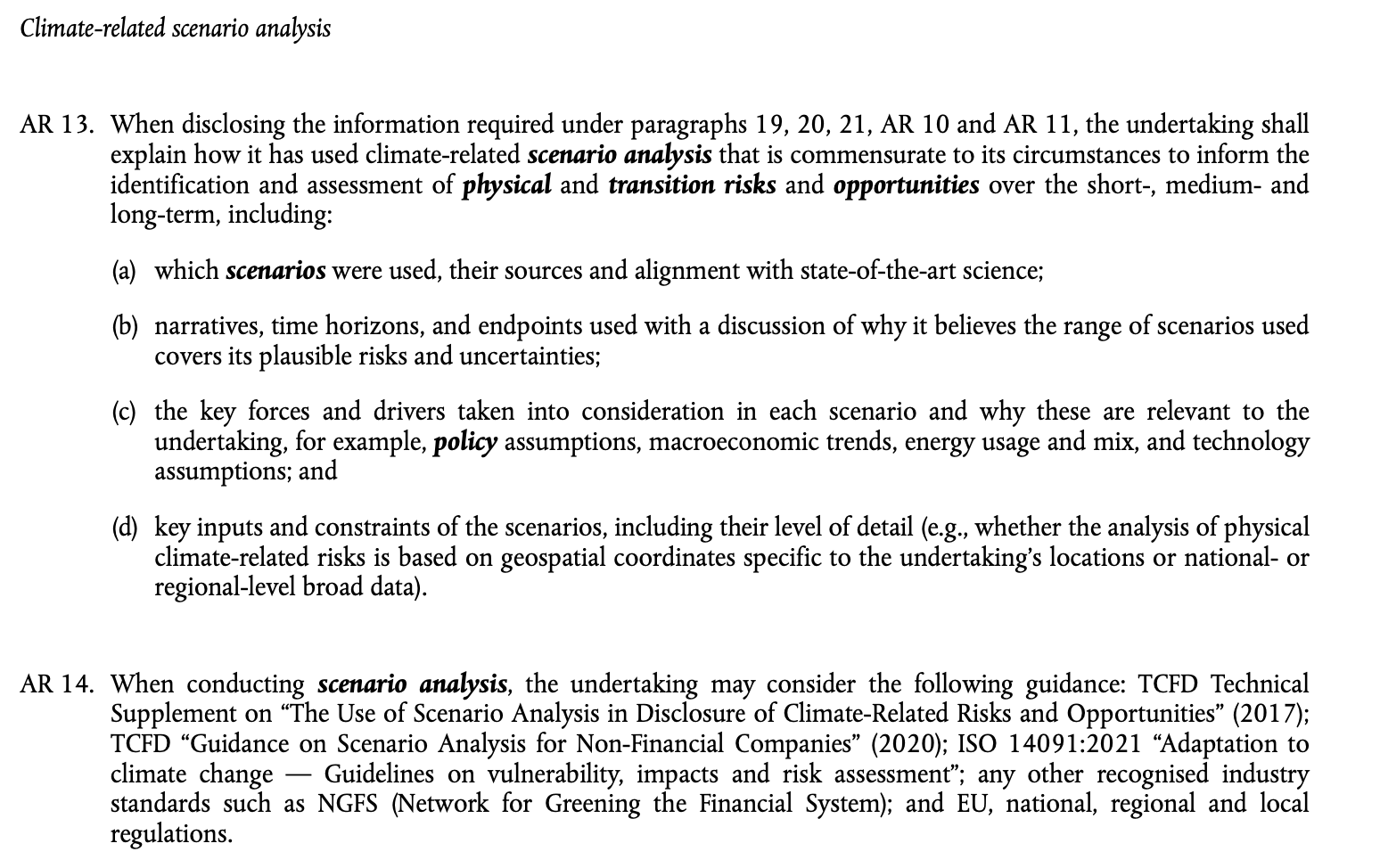

For this disclosure that on the surface seems to be a yes/no – “Undertaking has screened whether assets and business activities may be exposed to climate-related hazards” – we can see that AR 13-14 apply to it. So you need to open up the ESRS document and scroll down through it (it’s 284 pages if you download the English PDF – pro tip: add bookmarks to the major sections) until you get to the ESRS E1 section, and then scroll further within that section until you reach the “Appendix A” attached. Don’t think about searching for just “Appendix A” however, as there are multiple for different sections. (See what I mean about it being a nightmare? Who approved this?) Anyway, within the correct Appendix A we scroll down to AR 13 and 14, which is about climate-related scenario analysis, where we read this:

Ah. So what we might have been tempted to think was a simple yes/no answer now also entails explaining how we did this scenario analysis including which scenarios (i.e. which IPCC Representative Climate Pathways we used – the projections for global temperature growth over the next hundred years or so) and what stories we drew on, the time-frames we applied to our analysis, and even why we think it covers plausible risks and uncertainties. On top of that, we must explain the dynamics that emerge out of these scenarios, such as “policy assumptions, macroeconomic trends, energy usage and mix” and so on. Does that explanation have to appear in the same section as this disclosure, or is it something that can be placed upfront, and linked to? I am genuinely unsure – perhaps the answer is in ESRS 1 which is a list of general rules for preparation and conventions, containing no data points itself. (note, that’s not the ESRS E1 or ESRS S1 just ESRS 1… who approved this naming convention!!)

If your head is spinning or your eyes are glazing over as a wave of impossibility threatens you, then you have my sympathies! This is what it is like, and it is a monstrosity. It is entirely the case that the ESRS is also the most comprehensive disclosure system on the planet that I know of. It is the method that the EU has chosen to govern the corporate climate crisis, and it fills me with real apprehension.

The weaknesses are plain to see to anyone who has actually tried to use it. Why would anyone design a system like this? Who does it benefit? Who is it really for? It sure makes a huge and attractive new market for software providers who will be claiming their systems are Fully ESRS Compliant and maybe they are – at tremendous cost. But for anyone else, if you asked someone to come up with a system of sustainability reporting that was guaranteed to turn the most ardent ESG defenders into a teeth-gnashing hater, you probably couldn’t do much better than this. Actually, if you told me someone had designed this to sap the goodwill and desire to do the right thing in every corporate ESG professional in the world I would believe you. It’s certainly going to do that for the majority who don’t pay for a platform “solution”. One that may largely automate disclosures for them and potentially remove any incentive or requirement to reflect on, understand, or have direct contact with the processes and procedures that are producing these emissions in the first place. Maybe it won’t be that bad. We will have to wait and see.

Granted, there are concessions for SME’s. The full ESRS is only made for “Large” companies – but you might be surprised by what “counts” as large to the EU. Quite a few successful game businesses that are nowhere near the scale of a Ubisoft or a CDProjektRED are still close to or above the “Large” bucket thresholds and will have to report on FY2025. The cut-down ESRS list of datapoints that applies to listed SMEs (called the LSME – because why not throw another acronym at the pot at this point) is still quite extensive.

So how do we assess the ESRS? Is it going to become just a bureaucratic hurdle, or is it going to produce transformative change? Truthfully, it’s still impossible to tell. There are certain disclosure requirements of the ESRS – like having and describing a “transition plan” – which might be good. The details of that are still in development. It will, or should, also produce a ton of new data for analysts and observers like myself to sift through. Lots of dark corners will (hopefully???) finally get a light shone on them.

But where does it fit in the global governance landscape? It's a technocratic nightmare, for one: a Brussels-based broadside of EU bureaucracy pointed at the problem of sustainability. But it is also (deliberately or otherwise) a neoliberal dream, solving with markets, creating an exciting new space for B2B “Solutions” and PureGreen™️ Platforms for One Click ESRS CoMpLiAnt Disclosures – buy now! From one perspective, it's a “level playing field”, but from another, it looks like just another way to entrench competitive advantage via administrative burden – a jungle that only the biggest companies with the biggest teams can cut their way through unscathed. It might also just be part of the broader European malaise when it comes to competitiveness. I don’t know. Some of this is beyond my pay grade.

What I do know is that the more time I spend with it, the less and less full-throated I am in my defence of this important piece of sustainability legislation. The longer I spend with it, the more caveats I have to attach to my descriptions and endorsements.

It certainly doesn’t look like an “alternative” in any meaningful sense – at least, not yet, not from here and now. Maybe it gets there, with refinement, with practice, and with a bunch of help and goodwill it probably doesn’t deserve from the people who have to implement it – I don’t know. It certainly doesn’t count as a radical departure from the prevailing (investor-directed) ESG consensus, and it’s definitely not an alternative songbook to the neoliberal governance hymnal (unless you count devolution to draconian technocracy as an alternative! I guess there’s a case to be made…).

What would count? The ideas are out there, becoming less unthinkable with every passing day. They are, notably, not taking shape in the realm of corporate regulation – but they are being talked about. From public ownership of energy systems to the expansive and diverse field of degrowth research (with some, notable, counter-productive exceptions), to those who dream of a different kind of mode of production altogether. There is a hunger for something else. I don’t know what it is exactly. But it’s more… free. More democratic. More room for climate justice (though that's in there as a few data points ha ha ha!). It’s not the absence of rules or processes, clearly, but it would need a radically different spirit. EFRAG does a bit of public feedback and consultations and whatnot, but it's still a process that constrains rather than liberates. Again, I don't know what that would look like either.

Until I do, I will be at best an ambivalent, frustrated “champion” of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards – a necessary, flawed, and aggravating system. But it’s maybe the best we have. For now.