Net Zero and the games industry: Unpacking the United States 2050 strategy

By now, most will be familiar with the idea of net-zero targets. These are goals set by governments around the world for countries to achieve zero annual emissions, usually around 2050. Some are binding through legislation, some are aspirational, and some are simply attempts to neutralise domestic political issues (looking at you Australia). I wanted to take a look at some of the details of these targets, and the plans that different countries have released describing how they aim to achieve these targets. As the framing documents for grand policy for the coming decades, I suspect there are insights for the long term outlook on the digital games industry, perhaps even suggesting strategies for alignment that can make the task quicker and easier for everyone. Where better to start this sort of exercise than with the world’s largest economy, and the country where most of the world’s game development happens.

The Net Zero Tracker website is an invaluable resource, keeping tabs on the commitments of 136 countries, 116 different regions, and over 700 companies. They categorise Net Zero commitments against four areas: the status of the targets themselves (is there a target, and how are they expressed: i.e. in policy, or legislation) what kinds of emissions it covers, how detailed the plan and reporting mechanisms are, and lastly whether they include carbon removals (as well as rules around removals). These are useful for comparisons (which I’ll try to do as we look at different countries) and they also give a snapshot of a country’s progress so far.

Net Zero Tracker’s snapshot of the US’ plans state they are currently: in policy documents (i.e. not yet legislated – though the ‘Inflation Reduction Act of 2022’ has elements that support it), include 2030 interim targets, measures both CO2 and other greenhouse gases (like methane), but does not include not consumption, historical, or international aviation and shipping emissions. The plan is also “incomplete” meaning it doesn’t yet “outline expected emission reductions from proposed actions and measures, the extent to which each measure will be applied by when, and the binding review and updating process”. It does, however, have an annual reporting mechanism and refers to equity issues throughout – but there is no formal accountability mechanism if targets are not achieved. Finally, the US Net Zero Plan does not include the planned use of offsets or traded carbon credits (good) and plans for carbon removal from the atmosphere to help balance out the last remaining hard-to-abate emissions include both nature-based (reasonably good) and carbon capture and storage (arguably, less good).

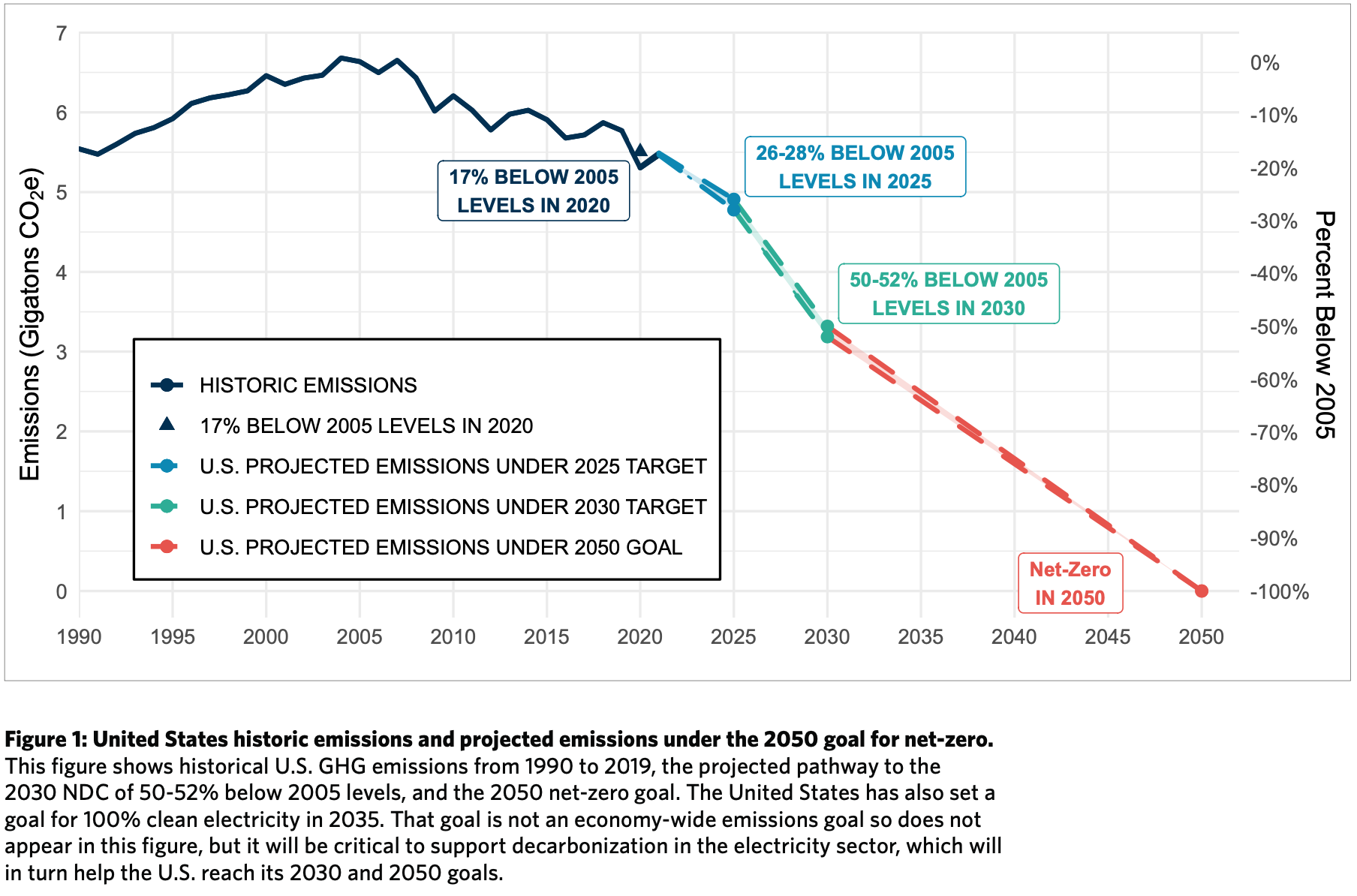

So the main Net Zero 2050 target for the United States exists as a policy document – and it was released by the White House in November of 2021. This is what I’m going to dive into in this post, as it represents the most detailed plan yet for how the US will decarbonise over the next 28 years. Here’s the key graph of projected annual country wide emissions over that period, demonstrating the steep, continual reductions needed as we approach 2050.

The document treads a fine line between high-level strategy and specific, known details across its 61 pages. How exactly it plans to achieve continual reductions over the next 28 years is critically important, and the level of transformation it describes is perhaps bigger than any in living memory. To my reading of it, the key section, and the critical pillar for the success of the overall strategy, is Chapter 4: Transforming the Energy System Through 2050. It describes the achievement of a net zero electricity sector – to be reached well before 2050 – and the whole of society decarbonization that it begins to unlock. This part of the strategy is also where we find most of our intersections with the digital games industry: emissions from power, emissions from buildings and the built environment all show up in the annual carbon inventories of game companies, large and small.

The plan opens by noting the present emissions context: “The U.S. currently emits 11% of annual global GHGs (second to China, which emits 27% of the global total).” China is the world’s largest emitter, at least in part because it has become the centre of the entire world’s manufacturing. The West (especially the United States) has over the past several decades outsourced the majority of the dirty, messy work of actually producing things to China and other parts of Asia. There are competing views as to who is responsible for those emissions – if they are ‘onshored’ and accounted for by the country of final consumption, then the current US figures would blow out substantially. There may even be an argument that Chinese emissions are subsidising the US net zero target – though we should be careful not to encourage competition as part of this already existential exercise.

The opening summary of the US’ Net Zero strategy lays out the stakes while leavening the challenging path ahead with a reminder of the many benefits a decarbonized future brings:

This decade will be decisive—and the benefits of achieving our 2030 goal will be significant. Transitioning to a clean energy economy will create between 500,000 and one million net new jobs across the country this decade. Moreover, reducing air pollution through these efforts will avoid 85,000–300,000 premature deaths. (13)

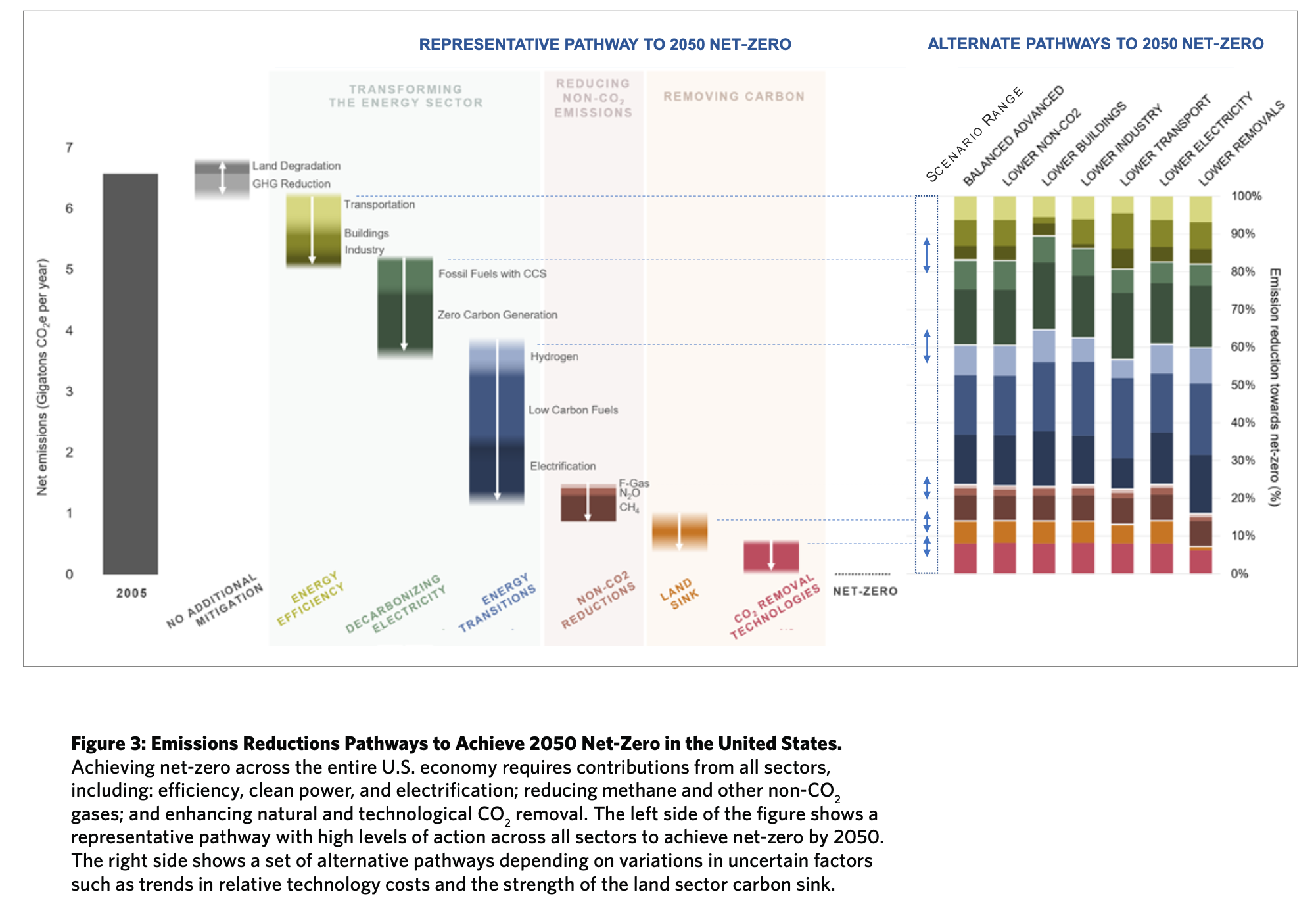

The report presents several pathways to achieving net zero, with different areas shifting their contribution up or down depending on the scenario. The big reductions in all scenarios, however are from two trends that go hand-in-glove: decarbonizing electricity production, and what the report calls ‘energy transitions’, or converting fossil energy inputs (gas heating, internal combustion engines) to electric ones.

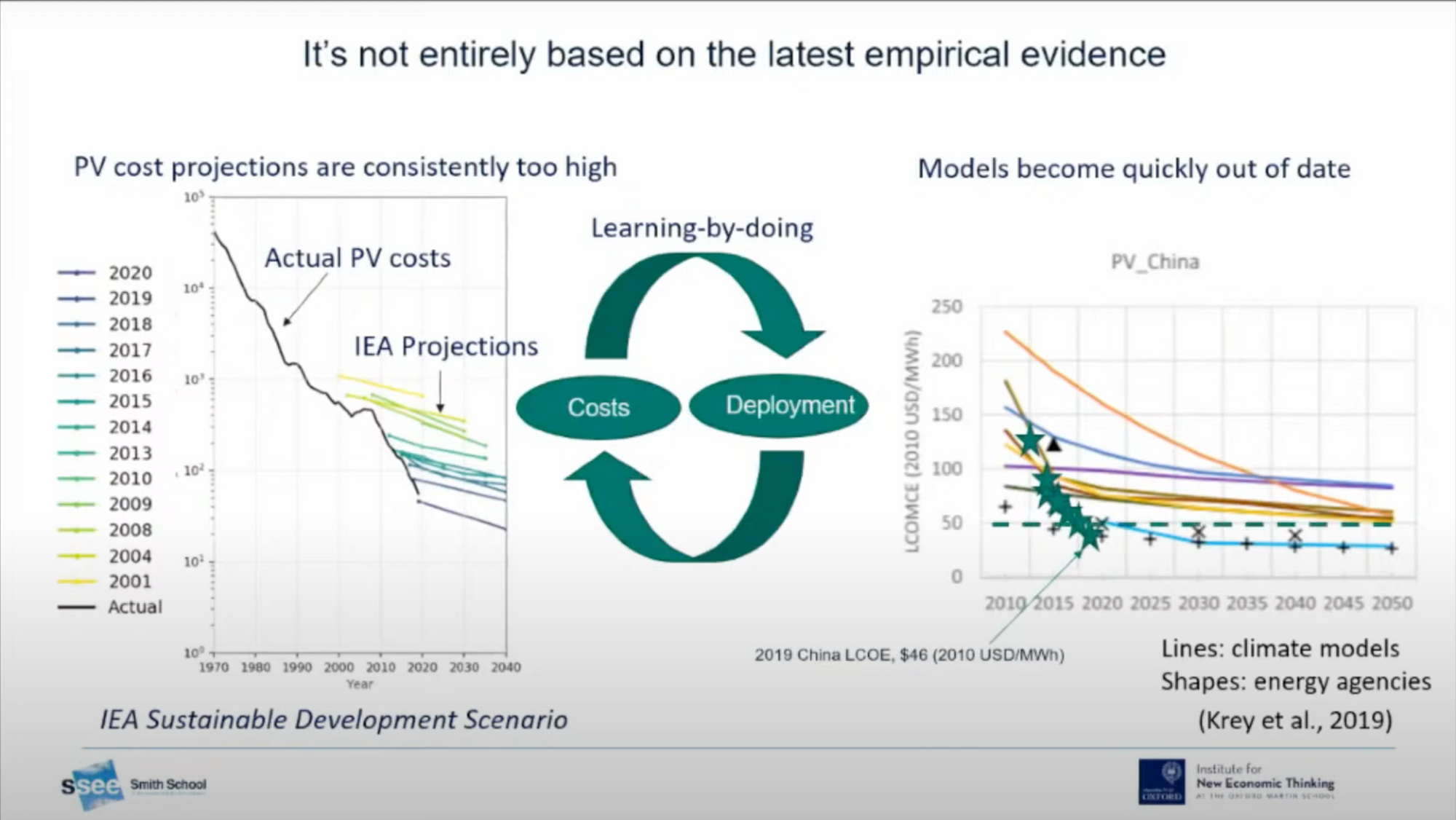

The graph above illustrates the huge reductions enabled by the shift from fossil based energy to renewables. Electricity generation in the United States “is currently the second-largest producer of emissions“ (14) (transport is the largest “representing 29% of all U.S. emissions” (30)) and achieving a low emissions power sector is absolutely critical. A fully renewable power sector is also within reach much earlier than 2050, with a feasible target of 2035 – just 13 years from now. This 2035 target is within the realms of possibility as “continued cost reductions in generation and storage are expected to enable even more rapid reductions of emissions from this sector.” (26) Other research supports this optimism. The following slide from researchers from the Oxford University Institute for New Economic Thinking illustrates just how cheap solar panels have gotten, and how conservative past projections of price decreases have been.

It’s a hugely encouraging picture and I encourage anyone with an interest in the economics of renewables to check it out (it’s the 2nd of three talks, starts about 21mins in).

A fully renewable power system, according to the Net Zero plan, unlocks reductions in other areas: “achieving 100% clean power generation by 2035 will also eliminate upstream emissions from electricity and facilitate carbon-free and efficient electrification of appliances and equipment in buildings.” (15) This gives the games industry a solid long-term outlook, in which Scope 1 (on-site fossil fuel emissions) and Scope 2 (fossil fuel power generation) emissions get easier and easier to avoid – to the point where they almost solve themselves over the next 10-15 years. Current hold-outs, with little to no current interest or active planning for decarbonisation are going to end up achieving close to zero emissions across this timeframe almost by default. This is the sort of outcome I argued for in Digital Games After Climate Change: rather than trying to convince climate deniers and other blockers, we need route around them and make their objections irrelevant.

There is also good news about the price of electricity along this decarbonisation pathway:

Recent analyses suggest that wholesale electricity prices, on average, are unlikely to change significantly as we shift to a cleaner grid by 2030, with price impact estimates ranging from a 4% decrease to a 3% increase. Additionally, the transition to clean electricity is expected to reduce exposure of U.S. consumers to fuel supply shocks. (27)

Saving money on electricity is just one of the many upsides of renewables. Echoing this sentiment, the head of the international energy agency this year Fatih Birol, in an op-ed in the Financial Times wrote about the fallacy of the current high-energy prices being driven by renewables:

I talk to energy policymakers all the time and none of them complains of relying too much on clean energy. On the contrary, they wish they had more. They regret not moving faster to build solar and wind plants, to improve the energy efficiency of buildings and vehicles or to extend the lifetime of nuclear plants. More low-carbon energy would have helped ease the crisis — and a faster transition from fossil fuels towards clean energy represents the best way out of it.

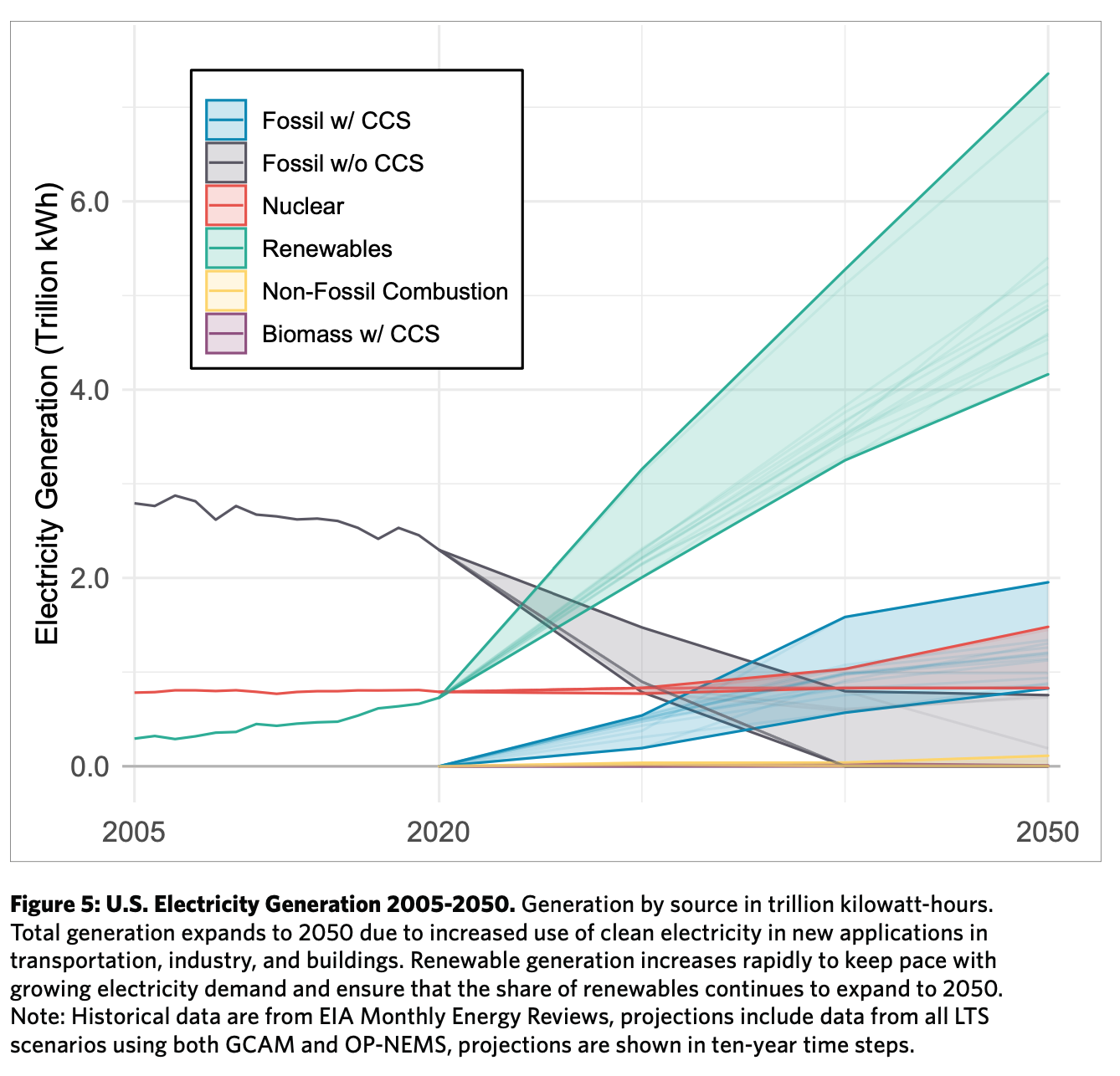

Moving into the heart of the details of the electricity chapter in the Net Zero 2050 plan, we are provided with a graph, projecting the long-term transition as renewable generation rises and fossil fuel generation capacity in the United States leaves the grid. The amount of renewables installed grows sharply, soaring from the current level of around 1 trillion kWh up to as high as 7 trillion in 2050:

These are some staggering numbers, but scaling up current generation levels by only around seven times the current existing capacity seems… feasible, at least, given the trajectory of solar and wind prices. The open question now seems to be less regarding cost and financing, than it is where these new installations will be located, and the process of approvals. Still, one way or another fossil electricity is leaving the grid, which will add a certain inexorability: “between 2010 and 2019, more than 546 coal-fired power units retired, totalling 102 GW of capacity, with another 17 GW of capacity planned for retirement by 2025 41.” (28)

So that’s the big ticket stuff – renewables and electrification, but what else can be done? Other intersections with the plan that the games industry can feed into and accelerate are in the area of energy efficiency, both in devices (hardware, AC, heating and cooling) and the built environment itself (better designed buildings, better use of insulation, smarter use of heating and lighting, etc.). This has been a major focus of communications by the International Energy Agency this year, and I have previously written on the benefits of greater energy efficiency here on GTG. These are all things that medium and large games companies will have an easier time with, and many actions that save energy also pay off by saving money. The effect of greater energy efficiency is to make a carbon free electricity grid even more achievable:

Significant deployment of energy efficiency can also help reduce the scale of investment required by lowering the total energy demand that must be met. (27)

The Net Zero strategy further raises the prospect of “grid-interactive demand to lower energy bills for households and businesses.” (15) There may be ways that games can take advantage of these demand-responsive systems as well, such as through deferring downloads at times of high grid demand – the prospect of which was raised as being ‘under development’ already when I spoke to Joshua Aslan from Sony earlier this year. Are more ambitious, bigger or better demand lowering strategies possible? Perhaps, though they do come with substantial tradeoffs, and some serious technical barriers to implementation. Scaling back resolutions, capping frame-rates, and the like all produce noticeable impacts, ones that players may dislike or object to. There is also the technical – and political – challenge of initially setting up these demand-responsive systems. An article for Canary Media this week described the state’s existing system and a recent demand-reduction event driven by asking customers via text message to shed loads:

At around 5:45 p.m. on September 6, as state grid operator CAISO was preparing to initiate rolling blackouts to stave off grid collapse, the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services issued a statewide text message alert asking people to “conserve energy now to protect public health and safety.” Over the next half an hour or so, demand dropped more than 2,000 megawatts below its record-setting peak of just over 52,000 megawatts.

The article goes on to argue, I think quite reasonably, that while this process demonstrates the power of demand side responses, a more equitable implementation would involve compensation to consumers who reduce their demand, and be more effective for it. Without it, “the state risks seeing a valuable set of demand-side resources fail to show up when the grid could use it.” More sophisticated demand-response systems are likely to come eventually, but in what form, and whether they make sense for the games industry to opt-into remain to be seen. There may be better suited, more responsive candidates before we get to games, for instance.

The Net Zero strategy recognises these new challenges facing electricity supply, and that existing configurations of power grid remain rooted in the paradigm of the 20th Century, which we are rapidly leaving behind us. Greater variability in both supply and demand will become the new normal, and it notes that “new policies, incentives, market reforms, and other actions will be needed.” (26)

Beyond electricity, the plan is full of details on how to address difficult industrial emissions, and reduce transport emissions (the largest source of emissions, as mentioned earlier). Among these areas, the report notes that

a few processes or activities that lead to emissions are currently difficult or costly to eliminate or have no viable existing substitutes, and despite many available cost-effective mitigation opportunities, non-CO2 GHG emissions cannot be fully reduced to zero. (24)

One of these areas with difficult to eliminate emissions includes “transportation segments, such as aviation, [which are] difficult to electrify and some legacy vehicles will continue to be necessary in the near term.” (31) I argued in Digital Games After Climate Change that the future of the games industry lies with digital distribution, and this shift contributes to reducing demand for freight transport emissions which are looking, still, frustratingly recalcitrant, which the Net Zero strategy acknowledges. Alignment with this aspect of the strategy appears a bit of a no-brainer, despite some of the other barriers that it poses.

The last major section of the strategy is emissions resulting from the design and operation of the built environment. It summarizes the current situation in the United States as

creat[ing]…high dependency on owner-occupied vehicles and presents numerous obstacles to alternate mobility options and shifting between modes such as transit, biking, or walking. (31)

The downside of suburban sprawl, under-investment in public transport, walkable cities, and efficient, dense buildings not only facilitates the US’ high transport emissions, but also high energy demand:

Homes and commercial buildings are responsible for over one-third of CO2 emissions from the U.S. energy system. Of this, roughly two-thirds of buildings sector emissions currently come from electricity. (31)

These are harder areas for the games industry to make useful contributions, itself, however it seem plausible to me that it may stand to gain from some of these shifts in attitude and expectation around cities and mobility. Just like how the games industry has seen a huge growth in remote working following the pandemic, giving greater access to wider talent pools and workers more flexibility, it may benefit from cities changing in sustainable ways. Cities that are more walkable, with better public transportation and more green cover, are often more desirable, and companies that locate themselves in these places may have an easier time attracting (and retaining) talent. These trends taking root outside the large capital cities could also help push against some of the centralising of game development in the traditional cities they cluster in: San Francisco, Seattle, Austin, etc. These are big, deep, and slow moving trends however.

The latter chapters of the Net Zero strategy frequently raises issues of equity, and the challenges remaining to be solved:

All buildings need to be decarbonized with an emphasis on strategies that deliver for overburdened and underserved communities. For example, in the residential sector, households with an annual income below $60,000 account for nearly 50% of all household energy consumption, making it essential that efforts to decarbonize buildings are accessible to all households. (31-2)

In many of these sections, what’s good for consumers is also good for many businesses:

Efficient and electrified buildings provide substantial consumer benefits. The most important benefit is reduced utility bills for households and businesses which are both direct (through lower energy usage) and indirect (through lower energy prices). More efficient buildings significantly reduces electricity demand and lessen winter peaking loads as the sector electrifies, reducing the cost of new generation, transmission, and distribution, which in turn reduces energy prices for American families and businesses. (33)

The many benefits the Net Zero strategy stands to bring become more frequent as the document goes on, with the final chapter devoted solely to it. Before we get there, however, it notes that: “more efficient buildings also retain indoor temperature for longer during power outages under extreme weather conditions, improving health and safety.” (33)

Chapter 6 discusses technologies for the removal of carbon dioxide, considered for the size of their potential contributions. Some – like planting trees – are well understood, while others like direct air capture (DAC) remain unproven at scale. Unknowns abound in this area, and yet the Net Zero strategy relies on them quite substantially. It notes that “some technical obstacles remain”, which is perhaps putting things mildly:

Research to date indicates that DAC requires high energy use for each metric ton of CO2 removed. Other technologies, such as enhanced mineralization, are still in nascent stages of research and development, so the potential magnitude of reductions and the timeframes over which these technologies might deliver reductions is unknown. (49)

This processes of ‘enhanced mineralization’ is interesting, but unproven. It involves is a carbon removal technique “that accelerates natural geologic processes around mineral reactions with CO2 from the ambient air, leading to permanent carbon storage through carbonate rock.” (49) A good friend of mine has long been an advocate for Project Vesta seeking to do just this, which “adds a carbon-removing sand made of the natural mineral olivine to eroding coastal systems. It reduces ocean acidity and removes carbon dioxide permanently.” Maybe this stuff pans out – maybe not. Worth a shot.

Finally, we come to the final chapter before the conclusion – all about the benefits of action, which are surprisingly substantial, with reductions in fossil fuel combustion translating into improved “air quality and [reduced] …dangerous risks of climate change.” (50) If these are too broad to have mass appeal, there are also more direct, measurable impacts, touching again on equity implications:

Reducing GHGs to net-zero by 2050 will simultaneously reduce other pollutants, including particulate matter (PM), ozone and PM precursors, nitrous oxides (NOx), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and other air toxics. These benefits will be more significant in communities overburdened by air pollution. (51)

It also highlights “emerging evidence that minor health impacts from air pollutants can also adversely affect educational attainment and reduce labor productivity” (51) though, again, these sort of nebulous public health benefits are harder to sell. Everyone stands to gain from these changes, however, and to me at least couching them in the language of productivity and benefits blunts their impact. There’s not really any upside for individual businesses, either, if everyone gets better labour productivity from cleaner air.

This sort of approach doesn’t really make sense to me, though I understand why the policy apparatus may land on this kind of language. What I suspect is needed is the sort of emotional pull that produces real emotional investment in a better vision of the world. As an example of what I mean, here’s an episode of Not Just Bikes which challenges conventional thinking that cities are loud. Instead, it's really cars that are loud. (Skip to 4mins 50seconds for the key bit)

I live in an outer-suburb with aspirations of being a city. It's on the edge of Sydney, and I live on a fairly busy road. For almost all the time I’ve lived in Sydney, I’ve lived on busy roads. I would kill to live in a city as peaceful and quiet at Delft.

As Jason of Not Just Bikes says in the video: “It’s really enjoyable to be here. There’s a sense of calm and peacefulness that you get when going somewhere quiet.” Fossil-fuel free cities are often quiet cities as well. They are pleasurable cities. We can talk about health benefits till the cows come home but until we show people how enjoyable a Net Zero world is, I think we are missing out on an incredibly powerful tool. Is this an area where games can help illustrate to players what a better future might look like? Maybe. I have explained my reservations with a certain type of didactic game, however, both in DGACC and this earlier piece. If it’s done it has to be done in just the right sort of illustrative, seductive manner.

The final comment I want to highlight from the Net Zero strategy is this, which perhaps bells the cat a little bit:

Although the overall economy will benefit from the transition to carbon neutrality, certain fossil fuel-dependent sectors and regions will have a more difficult transition. (54)

It’s impossible to stress just how much the fossil fuel industry stands to lose – and just how hard they are fighting, and will continue to fight, against this plan and the urgent transition. Delay and distraction are their current tactics, and are likely to continue. It’s also worth stressing just how big and bold this plan is, in spite of some of the shortcomings (like relying on unproven carbon dioxide removal technologies). It will also take effort – from everyone involved, which is all of us really – to ensure the benefits do not accrue solely to the already well-off:

It will require ambitious action and investment grounded in intensive engagement with communities, workers, and businesses to ensure that the benefits of the transition are equitably distributed—with a focus on those communities that remain overburdened and underserved. (17)

It is still hard to say, precisely, what sort of actions this sort of commitment will involve for individual businesses and entire sectors. What can the games industry do to ensure greater equity through the transition? Where can it (re)distribute gains and uplift underserved communities? These are important questions to ask ourselves in the years ahead.

Renewables, as I keep saying to anyone that will listen, are the closest thing we have to a silver bullet, and they will help keep electricity prices down – this is an equity win, surely. If the United States can fully decarbonise its power system in just 13 short years then the whole world will be in a substantially better position, and the carbon footprint of the games industry will look substantially different. It should look substantially better than it does from here.

Thanks for reading Greening the Games Industry – this one took a lot longer than I expected, but I hope it’s been worth the wait.

If it’s been useful to you in some way – whether it's clarified an aspect of the challenge, or just sparked some ideas for you – whether you’re an indie dev, or the leader of a huge global company: would you let me know? I love hearing from readers.

Feel free to share it with a friend or colleague who you think might enjoy a deep dive into the long term emissions trajectory of the US. Word of mouth is a huge part of how GTG reaches new readers and achieve the mission to build a movement for swift decisive action in the games industry.