The Big Scary Number

Last year I spent a couple of months’ worth of newsletter entries trying to figure out the greenhouse gas emissions associated with different parts of the games industry, trying out different assumptions and methods. I never managed to arrive at a single “big scary number” that reflected the true global climate impact of the games industry. But I think we’re closer than ever before.

Since last year, data disclosures have improved slightly, and we’ve seen new research from leading climate organizations like the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) and the Oxford Net Zero Institute (both of which I tried to summarise in the SGA Scope 3 briefing paper). I’ve also added even more games companies and their climate disclosures to my database for this year’s net zero snapshot – but even with a couple of the biggest companies’ disclosures outstanding we are already nearly equal to the total disclosures from games biz I added up last year.

But I’ve also come up with another, slightly different way of triangulating the total footprint of the games industry, drawing from a new-ish (April 2023) release from the US EPA which updates supply chain emissions factors (EF) we can use to calculate emissions based on dollars spent on goods and services. The EPA arrives at these emissions factors via input-output tables that take the entire economic production of a country (in this case, the USA) and the total GHG emissions output of the same, and slice that carbon pie into buckets based on different sector codes. In this case, they use the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) to produce an emissions factor for categories like “511210 Software Publishers”. This is a broad category, but it’s the best fit for game development, and it gives us a rough emissions factor – in units of kg CO2e per 2021 USD. The particular EF they provide, for those playing along at home, is 0.097 kg of CO2e per 2021 USD spent.

Why is this helpful to know? Because we now also have new projections on the size of the entire games business – i.e. as the sum of the prices paid by purchasers of games that is collected as revenue by game makers and publishers. Newzoo’s annual report-cum-forecast for 2024 just came out and pinned the total dollar value of the global games industry this year at around 187.7 billion dollars.

With that figure, we can multiply our supply chain emissions factor (0.097 kg CO2e per 2021 USD) by 187.7 billion dollars and (once we adjust for inflation) we get a figure of about 16 million tonnes of CO2e.

This is very reassuring (to me, anyway) because my net zero snapshot last year tallied up 7 million tonnes of CO2e emissions just from those companies that (mostly) made games. On top of that disclosure total I also predicted another 7 million tonnes of CO2e from the companies that weren’t disclosing, based off what we might expect them to report if they did (drawing on both revenue intensity and employee head-count emissions averages). So my 2023 figure of 14 million tonnes is starting to look pretty solid. But that’s not the end of the story – two essential things tell me that the true figure is even higher.

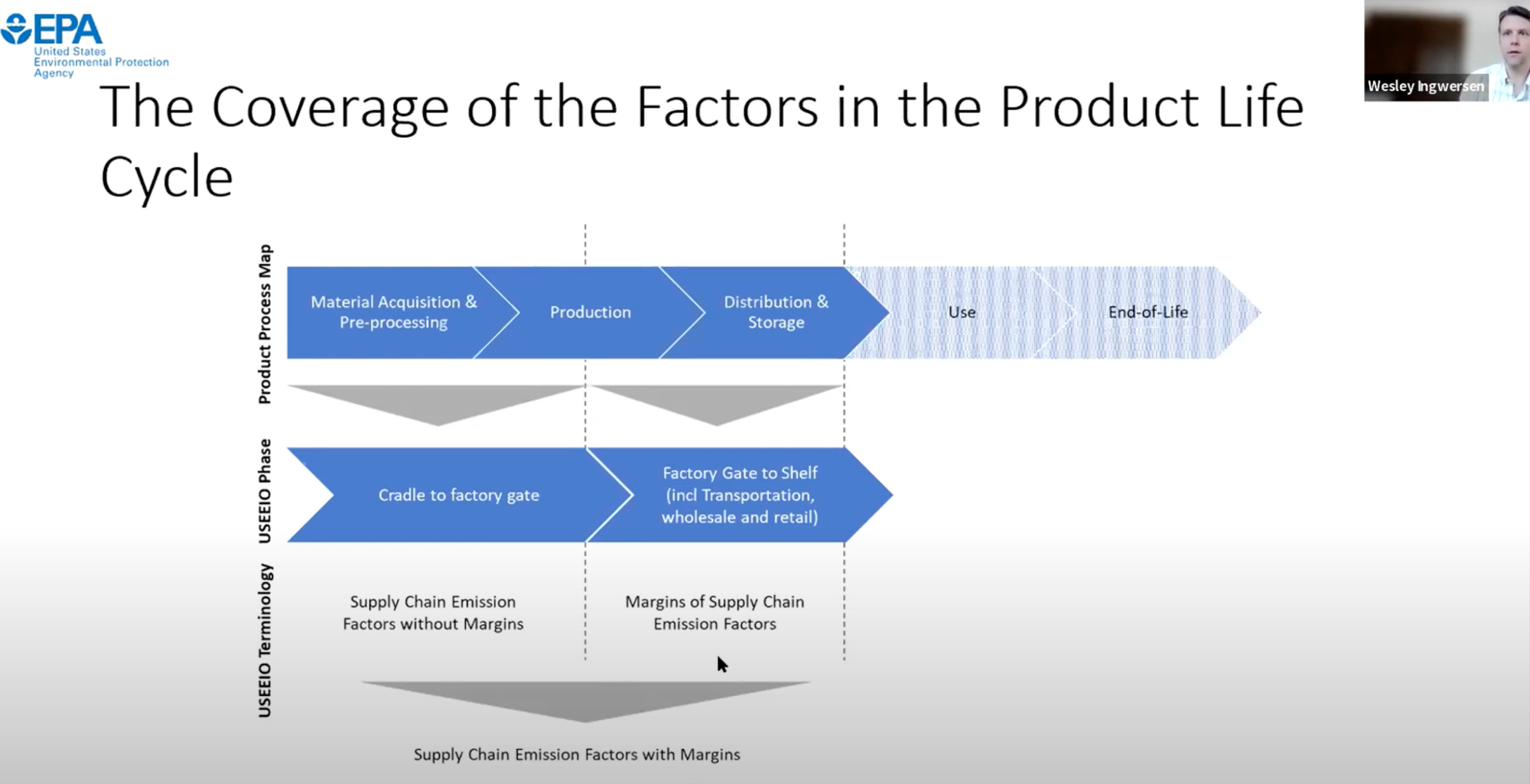

In the US EPA dataset, the supply chain numbers only account for upstream emissions – they are unable to account for the use phase of products or their end-of-life emissions. These supply chain factors reflect only the emissions from the raw resources required, from producing the product, and the transport/distribution to the point of sale to the customer. There’s no accounting for the use of products in here. This is the slide from the webinar that they provide to illustrate this.

This is not a flaw in the dataset or anything like that – it’s just that it’s way harder to measure use-phase emissions. Especially if you’re not the producer of the product, with too many assumptions required and so many different sectors. So the EPA doesn’t have the data needed to estimate the use-phase energy and emissions of every area (and imagine how hard that would be to do just for all software publishers in the US – this is sort of the challenge that we’re facing with the SGA Standard, coming up with accurate methods to measure end-user emissions with real integrity and transparency).

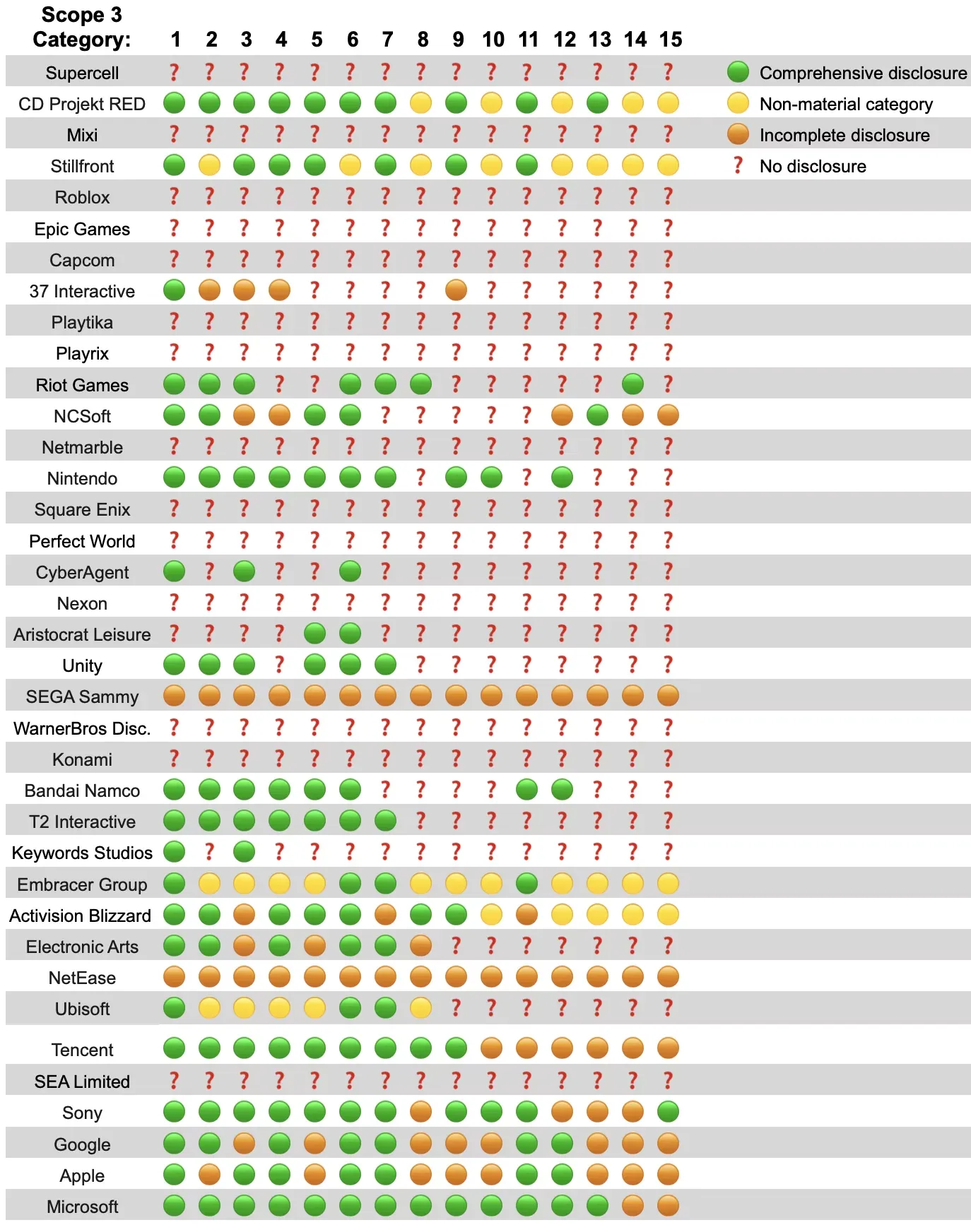

The second element which tells me that the 16 million tonne figure is too low can best be illustrated by a table I produced to show the very, very small number of game companies included in the net zero snapshot that are also measuring (or estimating) end-user emissions. In this table below, we’re interested in the column that is Scope 3, Category 11:

Besides the big tech companies, in 2023 only 4 out of 20+ game developers attempted to disclose the emissions attributable to gamers playing games. That number has increased slightly in 2024 to 7 out of 20+, but that’s mainly from the addition of additional companies I’ve started tracking.

One of the surprising conclusions I am coming to from this year’s data (though in hindsight I think it makes perfect sense) is that the smaller a game developer is, the more likely it is to be willing (or able?) to disclose end-user emissions. Perhaps the complexity of the challenge – which involves collecting huge amounts of aggregate time-of-use data, per-device energy data, global emissions factors for the entire world, and many other factors to boot is simply too big of a task for the already stretched ESG teams working on compliance and emissions reductions inside the more ‘classic’ operational boundaries of corporate emissions. Again, this is where I think an industry standard would be an immense help, by at least making the task simply graspable.

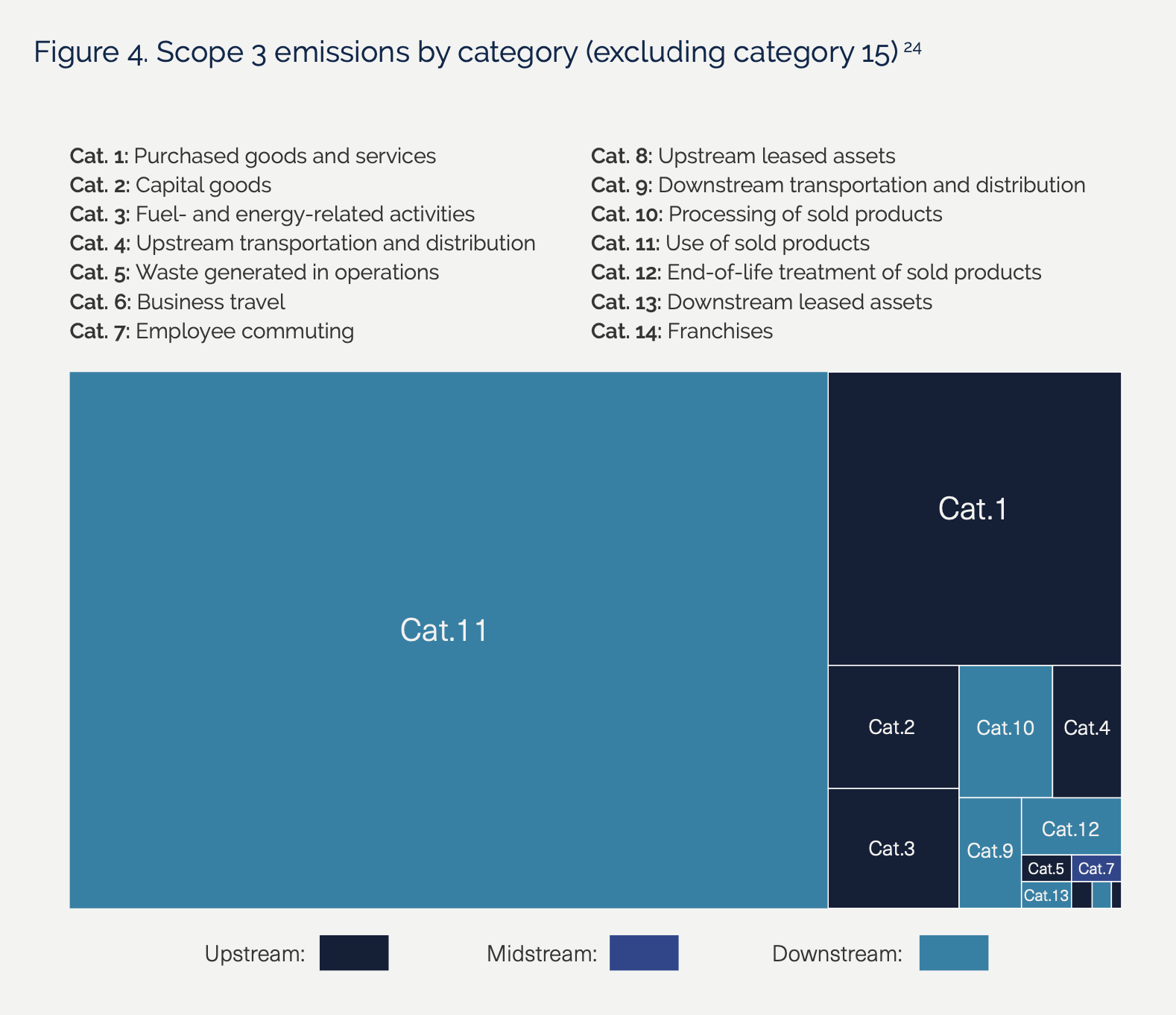

I think the idea that game developers can leave end user emissions up to someone else (who, exactly? the hardware manufacturers? governments? consumers???????) is dangerous. Why? Because the use of sold products is the single biggest category of Scope 3 emissions, if the SBTi’s research is to be believed (and who would know better than them – they literally validate the corporate world’s emissions targets!!!).

So what does this suggest for the total figure for the games industry’s global impact if this single category of emissions currently going mostly unreported is more than all the rest of Scope 3 combined? It suggests that we could double the figure and still be in the right ballpark: going from 16 million tonnes to 32 million tonnes of CO2e.

There’s one more data point that I think supports this doubling. This year, Ubisoft has started to put a number on end-user emissions. Here’s a reminder of what they said (with my emphasis):

In order to assess the impact of Ubisoft's games, we have drawn up an initial estimate of emissions linked to active game session hours over the year 2023. To do this, we have chosen to keep the scope small in order to ensure good quality data from our internal tools, our partners and our LCA. For this reason, our estimate is based on data from the actual use of our games and not on estimates over the life of the products as presented in the GHG Protocol method. The calculation methodology used takes into account the energy impact of our games on consoles with a screen.

We have therefore estimated that emissions from hours of gaming in 2023 was around 114 ktCO2e. This represents the equivalent of 80% of Ubisoft's total carbon footprint.

Yep, you read that right – Ubisoft’s end users alone are another eighty percent on top of the rest of their total footprint (which was 145 ktCO2e). Once you add in even more of the end users not included in this initial (high-quality) measurement I think you can quite comfortably double the total emissions of the entire corporate value chain once we start measuring users. This is obviously a big challenge.

But if it’s right, then Scope 3 Category 11 is the area with the biggest potential for positive impact if game developers can find ways to make reductions. That’s a big “if” but I think it’s worth thinking about since all emissions need to go to zero as fast as possible. There will be challenges to acting in this area, but I don’t think they’re insurmountable. I wrote about some of them in the SGA Scope 3 briefing paper.

A couple of other quick caveats I want to mention before we wrap up. First, is that the US EPA figures are based on typical US production methods. Other countries might make software (including games) in a more or less sustainable way, and using a global spend figure with a national supply chain emissions factor is always going to be a bit of a fudge – so keep that in mind. But as I think I’ve shown, the disclosures from international games companies themselves back up that this is at least not a wild overestimate. If anything, it’s probably still too low.

Secondly, there are still plenty of parts of the picture of the total games industry’s climate impact that remain uncaptured here. Three major sources I can think of that are barely registering in here are: Steam (so digital distribution, but also PC game players, and the entire Steam network layer), the hardware manufacturers and Big Tech companies like Microsoft and Sony (who I exclude because they have so much other business that clouds the picture) as well as the vast network of global data centre infrastructure which remains a really, really hard part of corporate emissions to get accurate data and estimates for.

How much higher does the figure go once you fold in all those other data sources? Your guess is as good as mine, but I think we could easily push the “big scary number” even higher: to 40 or maybe even 50 million tonnes of CO2e.

And remember, those emissions are per annum – every single year the games industry is spewing out emissions into the atmosphere at the rate of mid-sized countries (Sweden in 2022 was 38 million tonnes of CO2e, Norway was 40 million, Singapore 53 million). If you’re hoping (like me) that with all the positive talk about green games and new sustainability awards and initiatives and so on, that perhaps game industry emissions have peaked… well, I think I’m going to have some pretty bad news for you in a couple of weeks.

So something’s gotta shift – we’ve got to find ways to make and play games more sustainably. The Global Carbon Budget for staying under the threshold for dangerous levels of warming (1.5º or less) is set to be exceeded within seven years. A great place to start – the necessary place to start is with a sector-wide standard approach to measuring and disclosing these emissions that allows us once and for all to actually see clearly where the levers are that we can pull to reduce those impacts.

That’s what we’re trying to do at the SGA but we can’t do it alone. Please get in touch and discuss joining with decision-makers if you think our efforts are worth supporting because we can’t do it alone.