What does climate risk look like for the games industry?

The SGA Webinar we held the other week was great fun – we had a good crowd and some great questions at the end, and as promised the recording is now online.

If you missed it, or you just want to hear me talk about my understanding of the main features and impacts on the games industry from the European Sustainability Alphabet Soup – the CSRD, the ESRS, the CSDDD and the Green Claims Directive – the recording of the event is below (or on the SGA YouTube – please like + subscribe and all that).

To briefly recap: the CSRD sets the thresholds for when companies of different sizes report, the ESRS is the labyrinthine system for how companies are expected to report and on what data points and metrics, and the CSDDD is about ensuring the biggest companies in the world take sustainability and human rights seriously across their entire value chain (which means if you’re publishing on a platform owned by a CSDDD affected company, expect some detailed assurance requests!). The Green Claims Directive also makes illegal all sorts of non-specific Green Claims when they are made without comprehensive, clear, and detailed scientific evidence of superior green performance. That means “green games” marketing and communications need to come with the numbers and evidence to back up that claim. “We bought some carbon credits from a project in Timbuktu” won’t cut it anymore, in my opinion. We’ve already seen some prosecutions, and there’s real reputation damage that’s possible. Imagine being the first games company to be prosecuted for claiming sustainability without credible evidence for it. Wouldn’t live that one down quickly.

There are also some things that I had to leave out of the presentation because there’s only so much time and the details in certain parts are absolutely eye-watering. I think it’s a good place to start though, and we’ll be doing more of these as well as things progress.

Speaking of which – our next one in the series is coming up on Thursday the 25th of July, and this time it’ll be a more hands-on, more practical and applied workshop.

One of the new concepts that the EU has introduced is a requirement to take a “double materiality” perspective in ESG reporting. That means disclosing not just what impacts your business or organisation has on the planet itself, but also what types of impacts a rapidly warming planet may have on your business. The way most businesses have approached this issue is through the lens of “climate risk”, with TCFD disclosures (which I’ve shouted out in this newsletter previously) as the main mechanism for this.

So we’ve got some examples of the kinds of climate risks that games might face. Let’s take a look at some of what’s shown up in those TCFD disclosures, and then we can talk about what we’re going to do in the workshop this week that I think adds an extra layer of detail to our analysis.

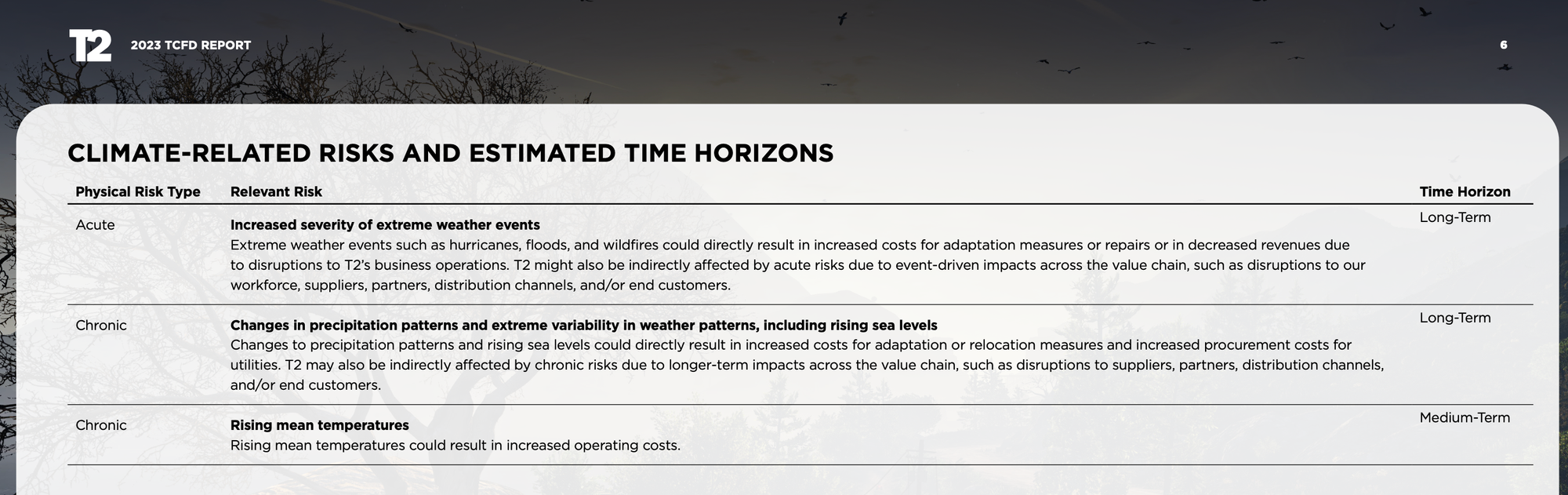

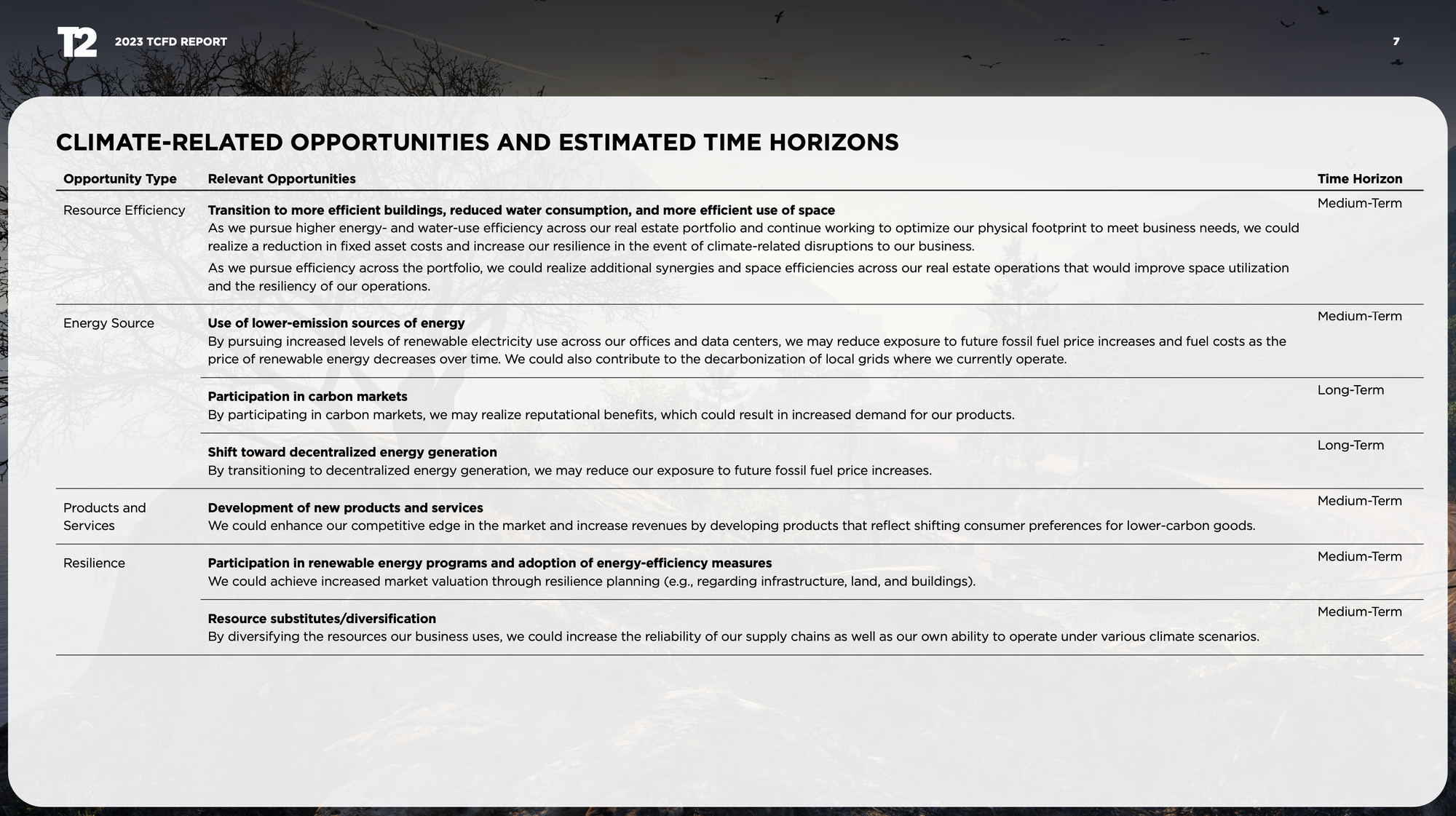

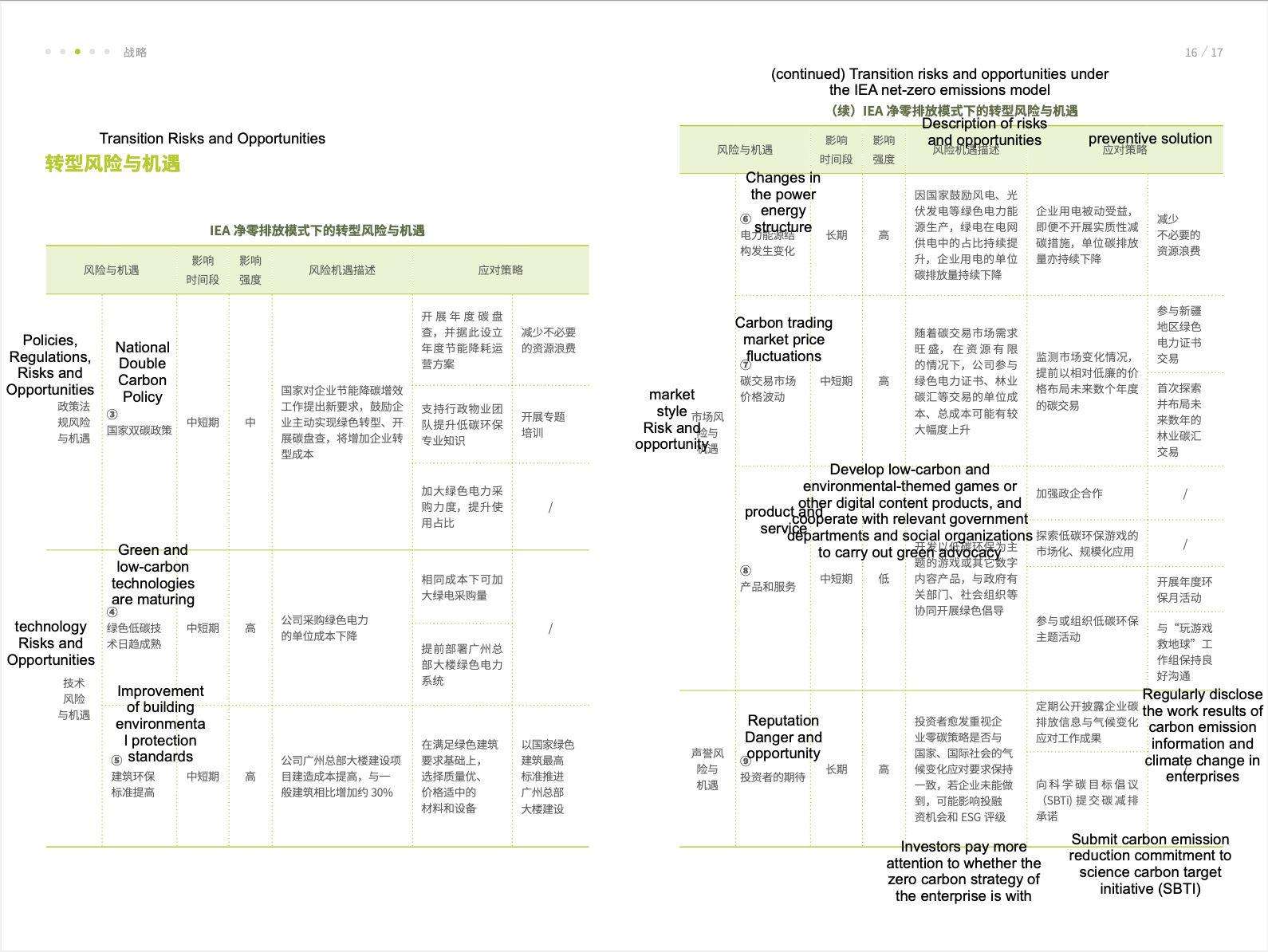

The disclosures under the TCFD come in three forms: physical risks which are things like fires, floods, extreme weather, and so on; transition risks which are the political and practical changes that may happen as the world undergoes this great experiment in living on a hotter planet (think, new carbon taxes, higher energy prices, changing consumer attitudes, and so on); and lastly opportunities like the ability to reduce long-term electricity spend by installing solar panels on offices, or the opportunity to appeal to sustainability-minded customers and employees by being proactive, and so on.

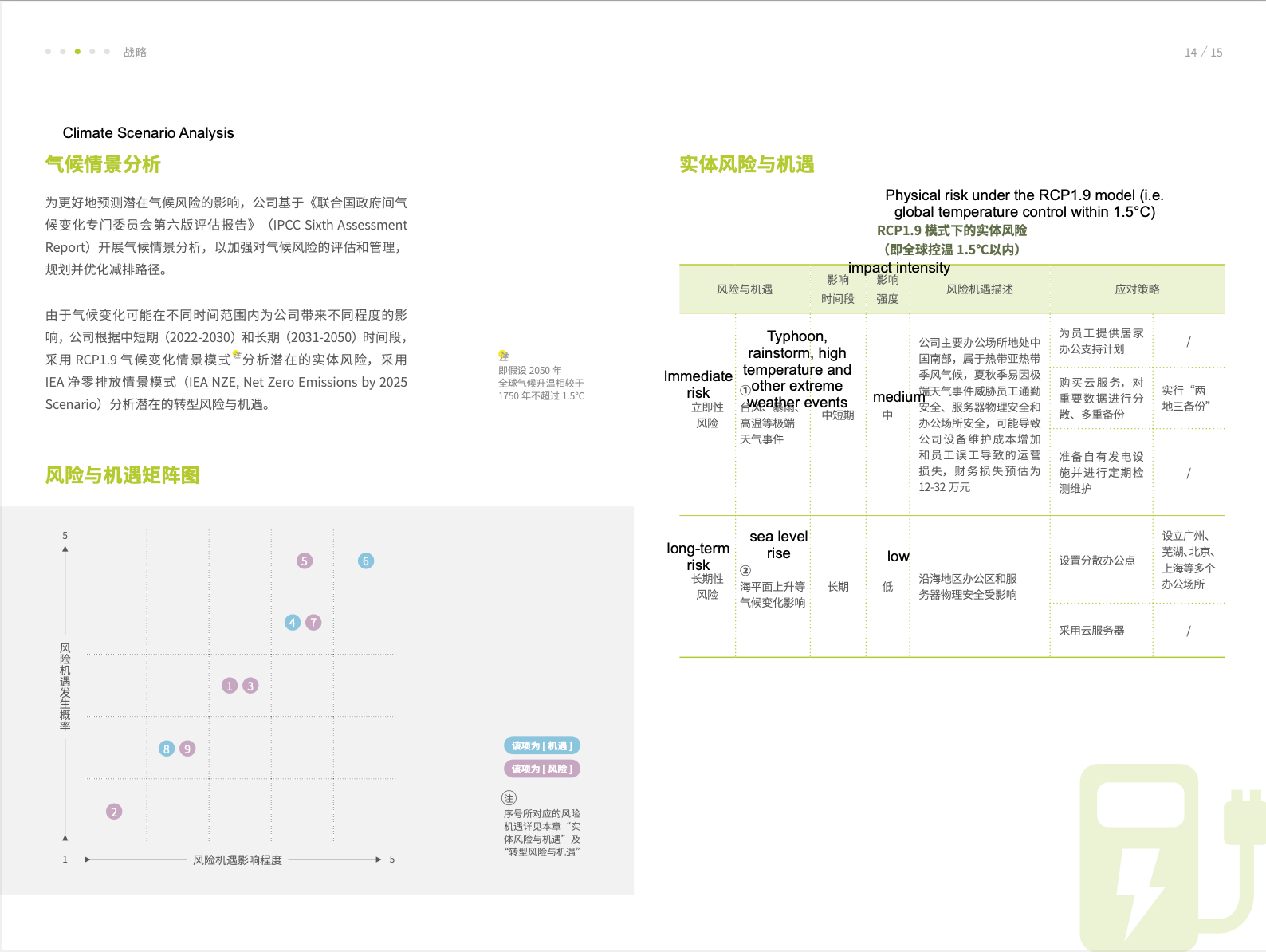

These risks can also be classified as “acute”, like say one-off storms that damage assets, or “chronic” in that the risks and impacts persist – such as the increasing frequency, number and duration of heat waves or the impact of ongoing carbon taxes. We can also place these kinds of risks (and opportunities) on a time horizon as well, specifying whether they’re likely in the short, medium or long-term, and we should also probably look at the scale of their realised impacts on different climate trajectories or “Representative Climate Pathways” (RCPs).

Here’s the risks and opportunities pages from the Take-Two TCFD disclosure back in 2023.

And here’s 37interative’s 2023 TCFD disclosure – with my English annotations.

So there are a lot of different dimensions to this exercise and lots of different physical risks to consider each with varying intensity and scale of impact.

But let’s get down to brass tacks - even the above disclosures, as good as they are, mostly tell us the big picture. What are the details of how these impacts might play out? Here it’s important to acknowledge that, because we are dealing with the future, we will have to be at least a little bit speculative. We simply can’t know with total clarity, but we can use our imagination and combine it with the latest and best climate modelling tools.

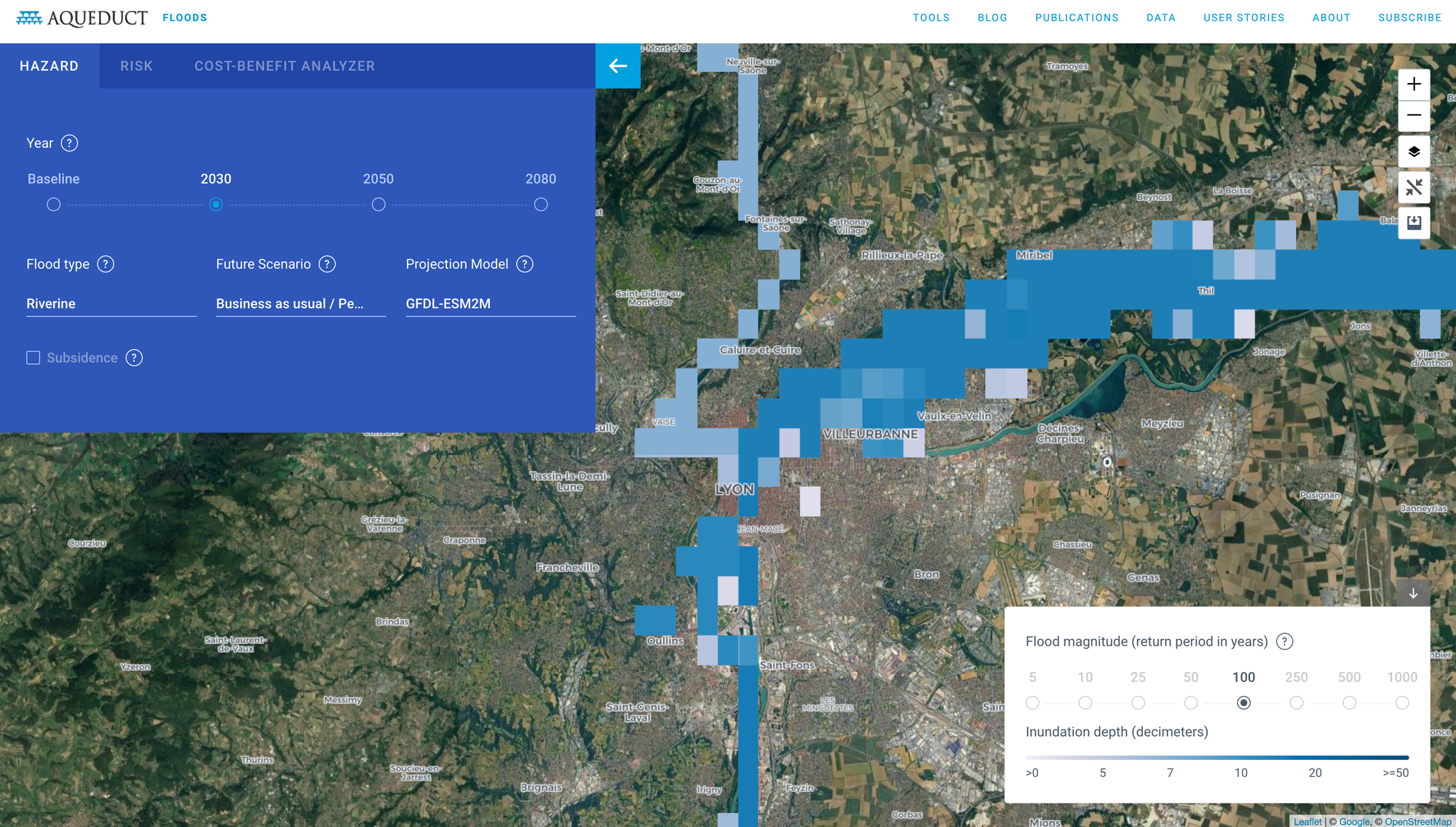

Let’s imagine we’re a game developer in Lyon, France. Maybe we have an office in the centre of the city, with a lovely view of the river. Well, what happens to our physical premises if a 1-in-100-year flood happens? (Which, as things are headed, is likely to become more like a 1-in-50-year occurrence, or even a 1-in-20: remember we’re loading the atmospheric dice towards way more water in the atmosphere and way heavier rainfalls.)

Here’s a (rather coarse, sadly) map of the depth of the floodwater in a 1-in-100-year flood scenario in the centre of Lyon. If our office is right on the Rhône riverbank in the northern part of the city, it looks like we might have trouble getting to or from the office when it’s under 1-2 meters of water. If we’re on the ground floor, there’s a chance that that flood might even get inside the building. This is an acute impact – a (hopefully) rare, and by definition uncertain outcome, but if the risk eventuates it could be potentially quite damaging, and cost serious money. Are our servers waterproof? I hope our off-site backups work! Does our insurance cover flooding? How much work time will be lost if employees can’t work from home? What about if their houses flood?

The EU’s double materiality approach requires companies to consider not just the direct climate risks, but also the indirect ones all along the value chain. So we might want to think about our business partners and players too.

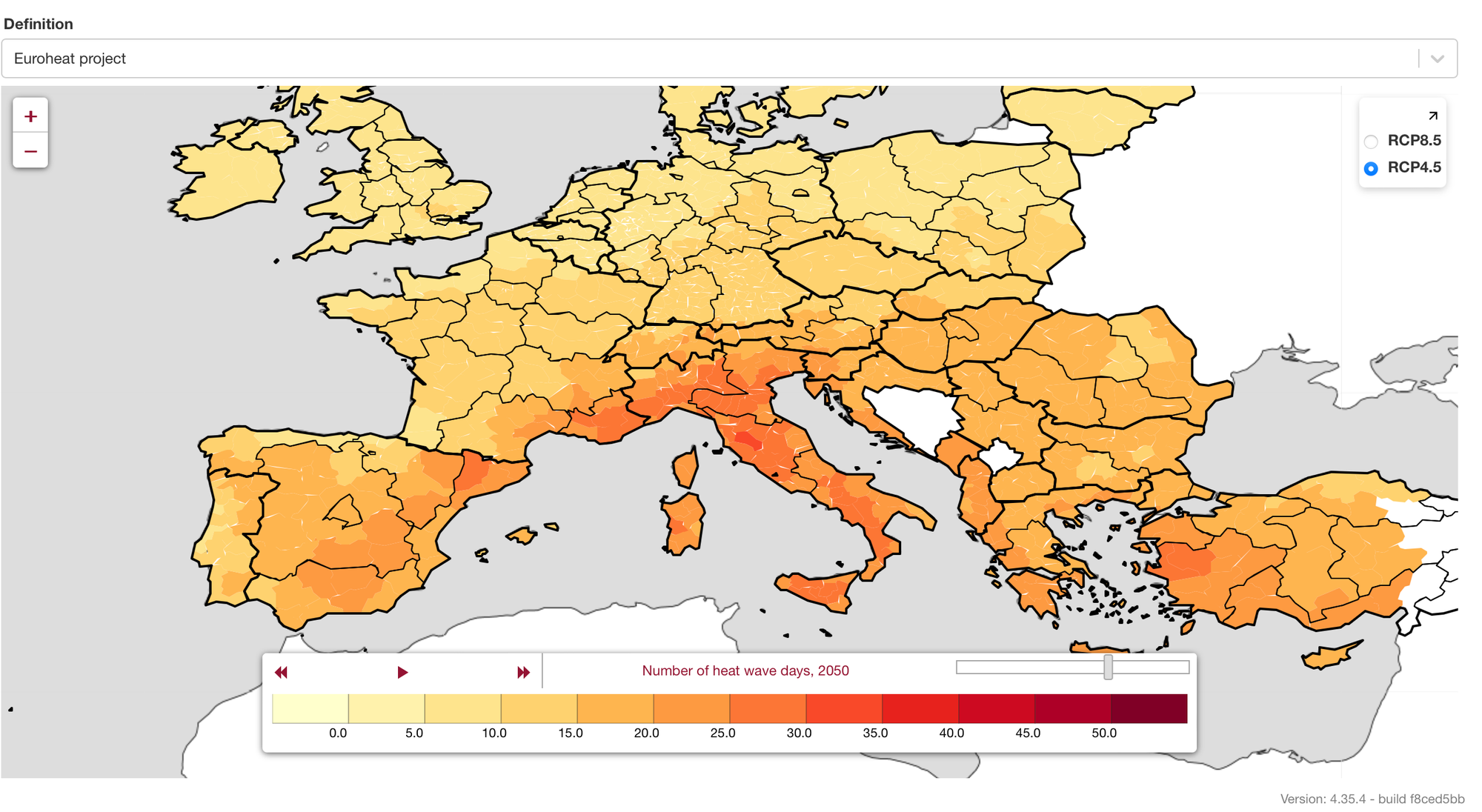

What happens if lots of our players are in Southern Europe – Spain, Italy, Greece? What changes can we expect to how they play, as things heat up? Can we make any informed judgments about how their inclinations to play games might change as heat waves become more severe and longer lasting? Here’s a map of the number of heat wave days expected across Europe in 2050, showing this still far-off hazard.

Getting up to nearly a month of heat waves is a bit much. Will that make players more likely to play games because they’ll stay home instead of going out, or less because they don’t want to add more heat to already hot houses? Or does power consumption become more of a concern? I grew up playing games in the sweltering Australian summer, and I often chose to do so, but not every time. Sometimes the extra heat just wasn’t worth it.

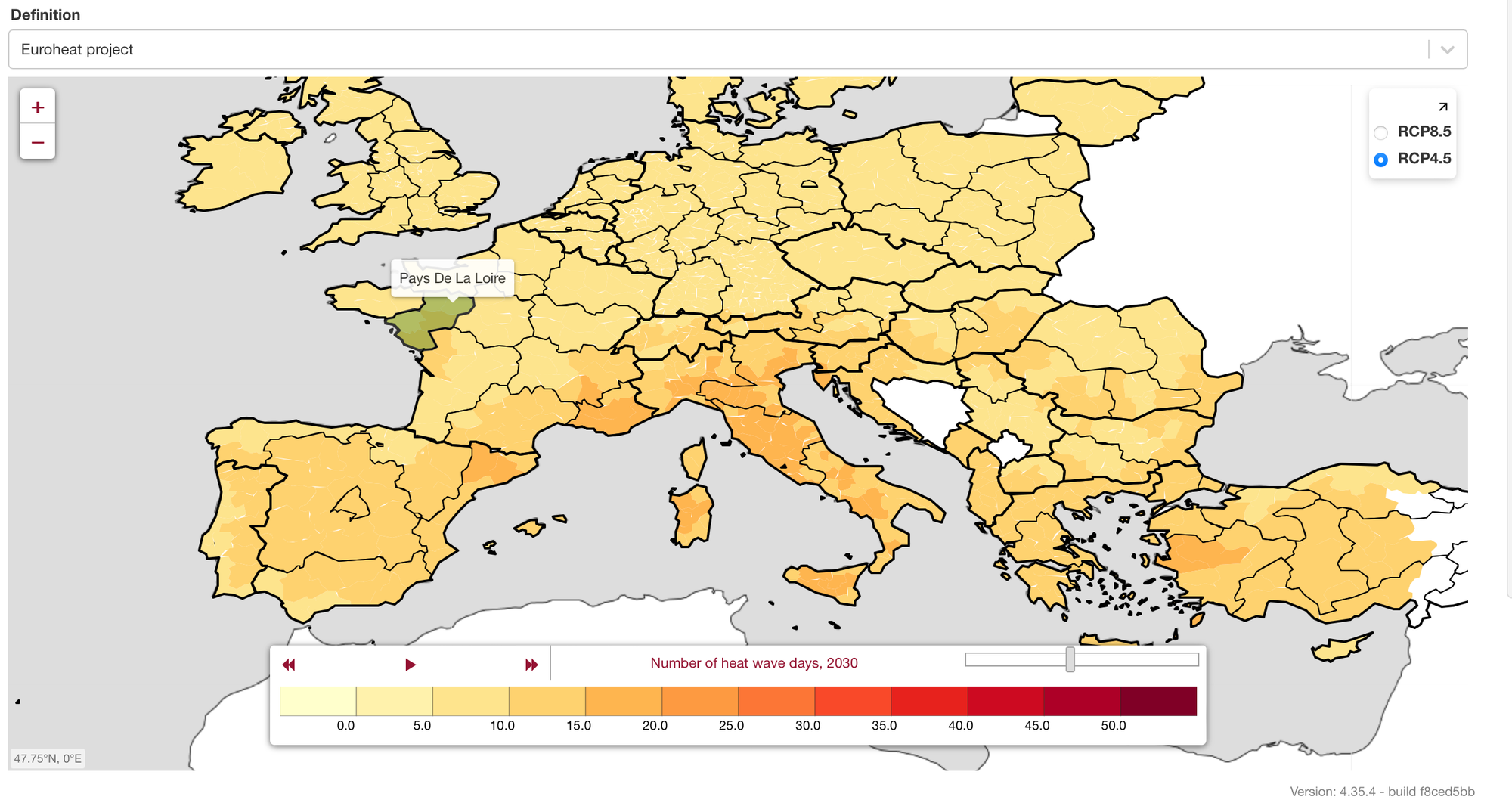

Okay, I hear you, 2050 is still a long way off – but even 2030 projections show we can expect half a month of heat waves in some parts of Southern Europe. This is going to be stressful, and it might have other impacts as well – maybe it increases energy costs from cooling offices or (if cooling isn’t adequate) it can sap employee’s productivity during summer.

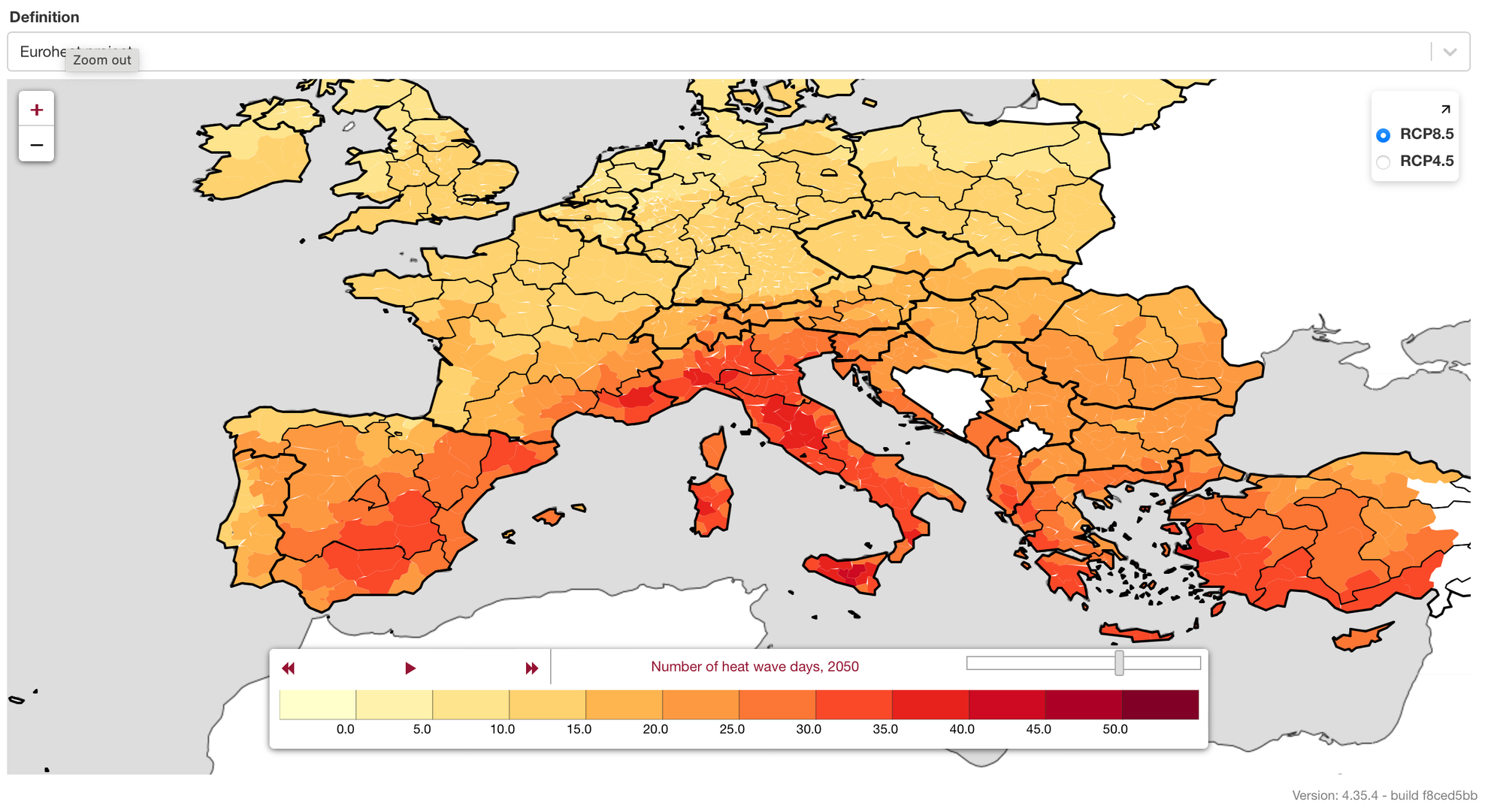

And these are both still assuming we achieve the RCP4.0 pathway – that’s only a temperature rise of between 2 and 3 degrees, which we are only just on track for. What happens if things get substantially worse? What if the anti-green backlash eventuates, decarbonisation slows down, the Trump wins in the US and pulls out of the Paris Agreement again? Drill baby drill means things get hot as hell.

Under the RCP8.5 “worst-case scenario” the Mediterranean can expect nearly fifty days of heatwaves a year by 2050. Can you imagine how utterly wretched that would be? Every summer stretches on and on in a waking nightmare of sweat and smoke from fires – and that’s before we get to things like crop failures, food prices, droughts, water availability… it’s almost unthinkable. Does that seem like business as usual? This scary climate outcome is still well and truly in the deck of cards – we can’t rule it out until we actually make global emissions peak. Nothing is set in stone.

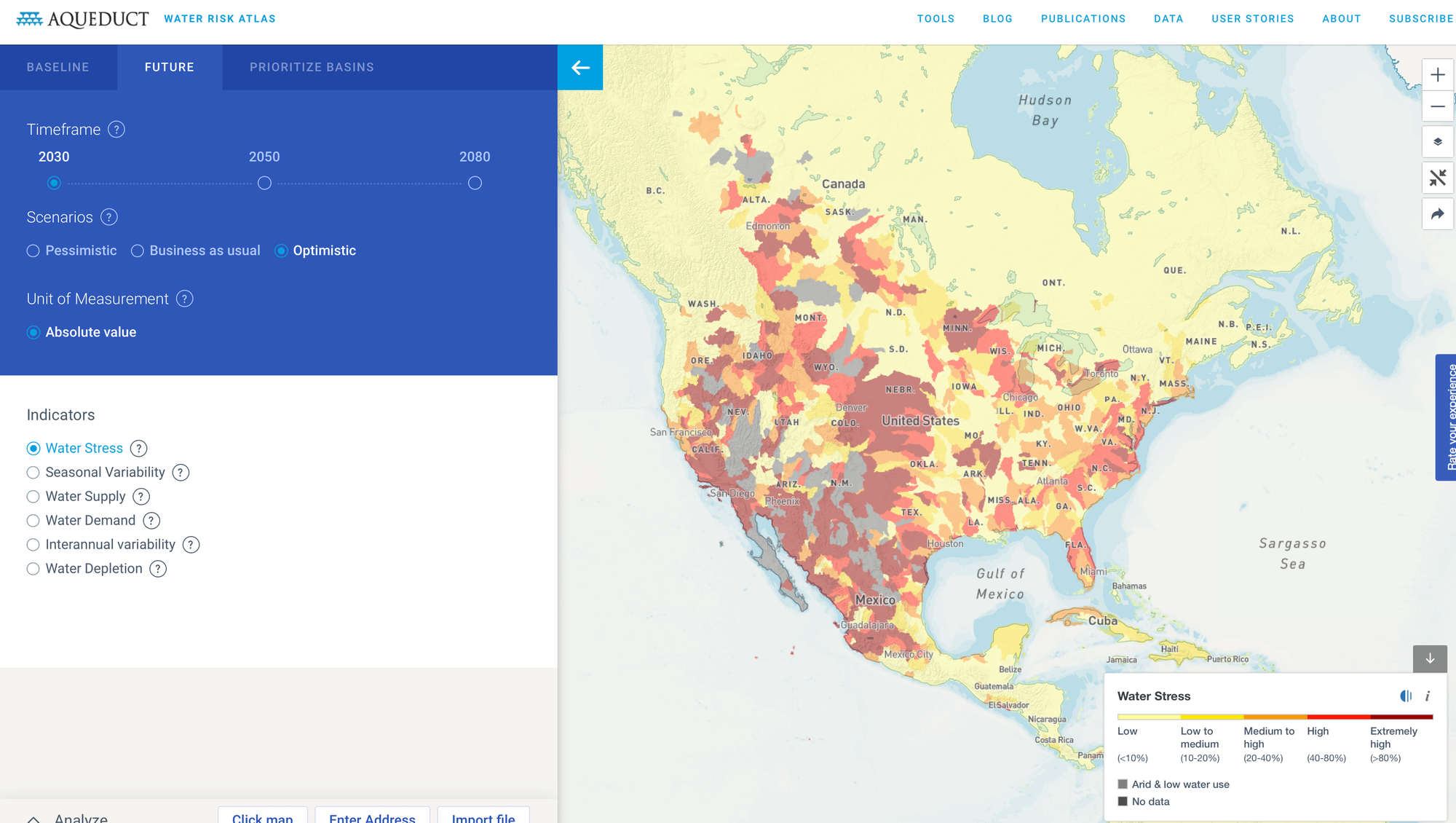

One last example – and this might be the most convincing one for game developers. In the world of live-service, always-online, and digital distribution of games a crucial dimension of many value chains is the resilience of data centres. Only the biggest developers in the world operate their own, so everyone else will be relying on third parties for compute, hosting, and other online services. Do you know where these data centres located? Do they have physical climate risks? On top of that, what is the source, the cost, and the emissions intensity of the power they use? Does the data centre use excessive amounts of water (often used for cooling the racks of hardware) or is the region it's located in one susceptible to “water stress”? Check out this "optimistic" water stress map for the United States in 2030. Water stress is a measure of the ability for a water system to adapt to changes in supply and demand, and there's a lot of deep red all across the continent.

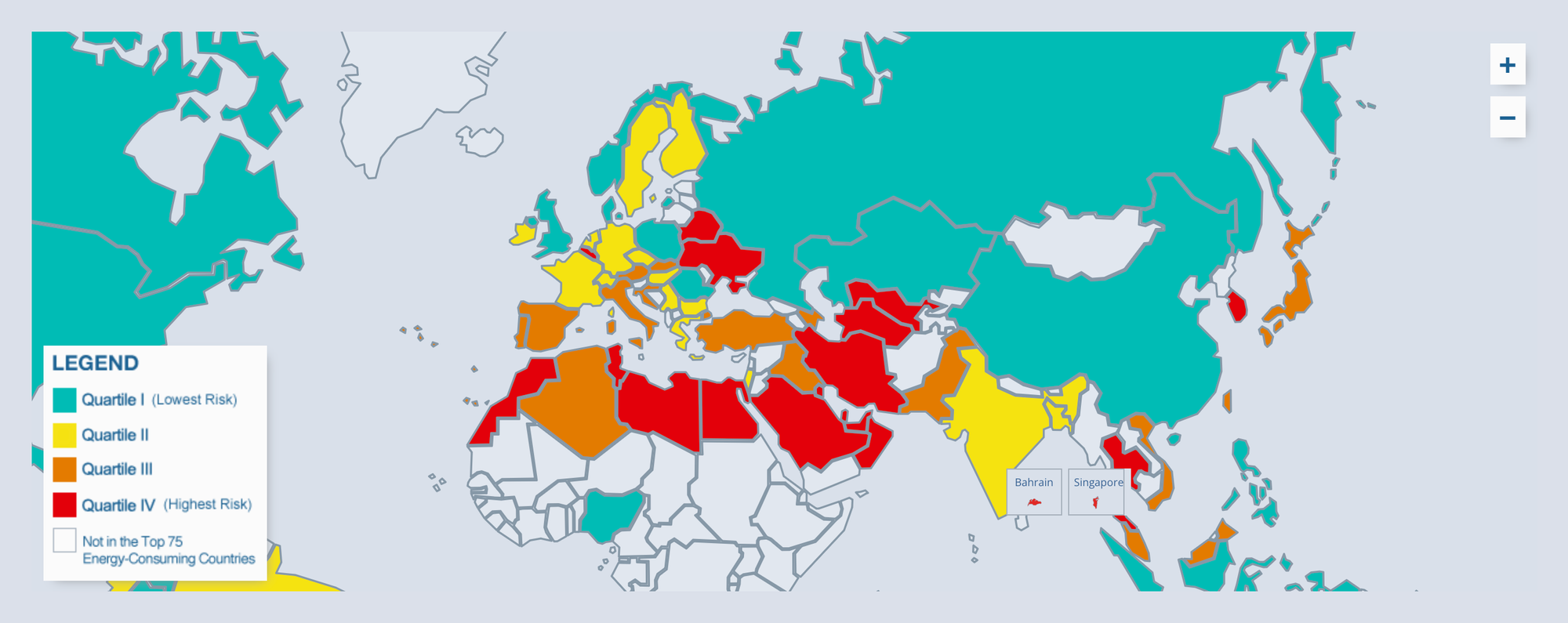

On each of these dimensions, we can look at different tools to evaluate the exposure to risk in this critical part of the game development value chain. Here’s another map (from 2018) ranking countries by the degree of energy security they have. What sort of uncertainty does this map speak to

Do you have infrastructure in any of these countries? Are reliability issues a significant risk? What happens when servers go down in your no.1 country, how quickly can they come back online, and what sort of losses might you face in different scenarios? Do you have large numbers of customers in South or South East Asia? We have seen how disruptive this can be, and precisely these kinds of climate impacts on power systems already – in 2022 droughts caused a shortage of hydropower in China which shut down factories. This is not the far-flung future, these are dynamic evolving risks that exist today, unevenly distributed as they may be.

Perhaps a country decides to get serious about climate in response to huge public demand and protest, and introduces a carbon tax – what does that do to power prices? Can your business model absorb a doubling of energy costs? Can your suppliers? Can your end users? Can we expect poorer gamers to shift to other, cheaper modes of gaming, mobile for instance, over console and PC? Maybe this presents an opportunity for existing mobile developers – I don't know for sure. But the dynamics of energy systems as the world moves to a greater and greater percentage of renewables are proving hard to predict.

Okay, so maybe you’ve got this far, you’ve looked at your business partners and your own infrastructure, and the exposure to fires, floods, and coastal storms (physical risk), and considered the political and economic ramifications of the green transition (transition risk) and you find yourself concluding “well, some of these are not great, but they are limited and don't directly impact me and my value chain”. In that case, great! Wouldn't you now feel better knowing that, rather than wondering, and living with the uncertainty? It’s probably never a waste to evaluate climate risk, even if it doesn’t directly hit you.

This is part of the process the EU wants to encourage with “double materiality” disclosures under the CSRD and ESRS – you can conclude that these risks are not material, so long as you have sound reasoning, and have done the analysis. Perhaps they’re only small hazards, easily remedied if they do occur, but it’s important to undertake the process, and who knows – maybe you turn up some unexpected risks on the way. Now that you know you can plan for it. Forewarned is forearmed.

So that’s the thinking behind Double Materiality – if you want to try out all these climate tools and get some guidance on how to apply them to your context, your game studio or your office, come along to the SGA workshop on Thursday this week. I can't wait to see you there.