Who still needs to know climate change is happening?

One of the main paradigms I still see many people framing climate action through is the lens of “awareness”. On one level, this is perfectly fine. Keeping attention focused on the issue so it remains at the front of people’s minds is clearly valuable. But I often see ‘awareness’ treated like something that some people are deficient in, and there are two assumptions that come with that.

The first assumption is that there is a cohort of people out there somewhere who still have never heard of climate change. I’m not convinced that this is true – but it needs to be for the second assumption which often sneaks in with this same discourse. The second assumption is that if people were aware, they would do something differently about climate change – presumably, either in their sphere of action (or lifestyle choices) or more generously, perhaps with their voting intention. That’s why we haven’t arrested dangerous climate change yet, right?

You can see how appealing “awareness” raising is as an answer – if only people knew then we wouldn’t be in this mess! Alas, things are rarely as simple as that, and I think we’re being led astray whenever we accept this framing. To challenge these assumptions, let’s look at what the research says about levels of the most elementary form of climate change awareness.

The first attempt at quantifying global awareness of climate change was published in 2015 (by Lee et al. 2015). However, it was based on Gallup survey data collected between 2007 and 2008, reflecting a much earlier state of affairs. In the study, the authors did a bunch of sophisticated statistical modelling that produced an incredibly rich data set and some hugely compelling findings.

Two of the authors, Yale climate communications researchers Anthony Leiserowitz and Peter Howe, summarised the top-line finding about global climate change awareness levels as follows: “About 40 percent of adults worldwide have never heard of climate change.” This would have been a bit of a shocking indictment of the success of climate communication, to be frank. But keep in mind – this is where the world was at almost 8 years prior to publication.

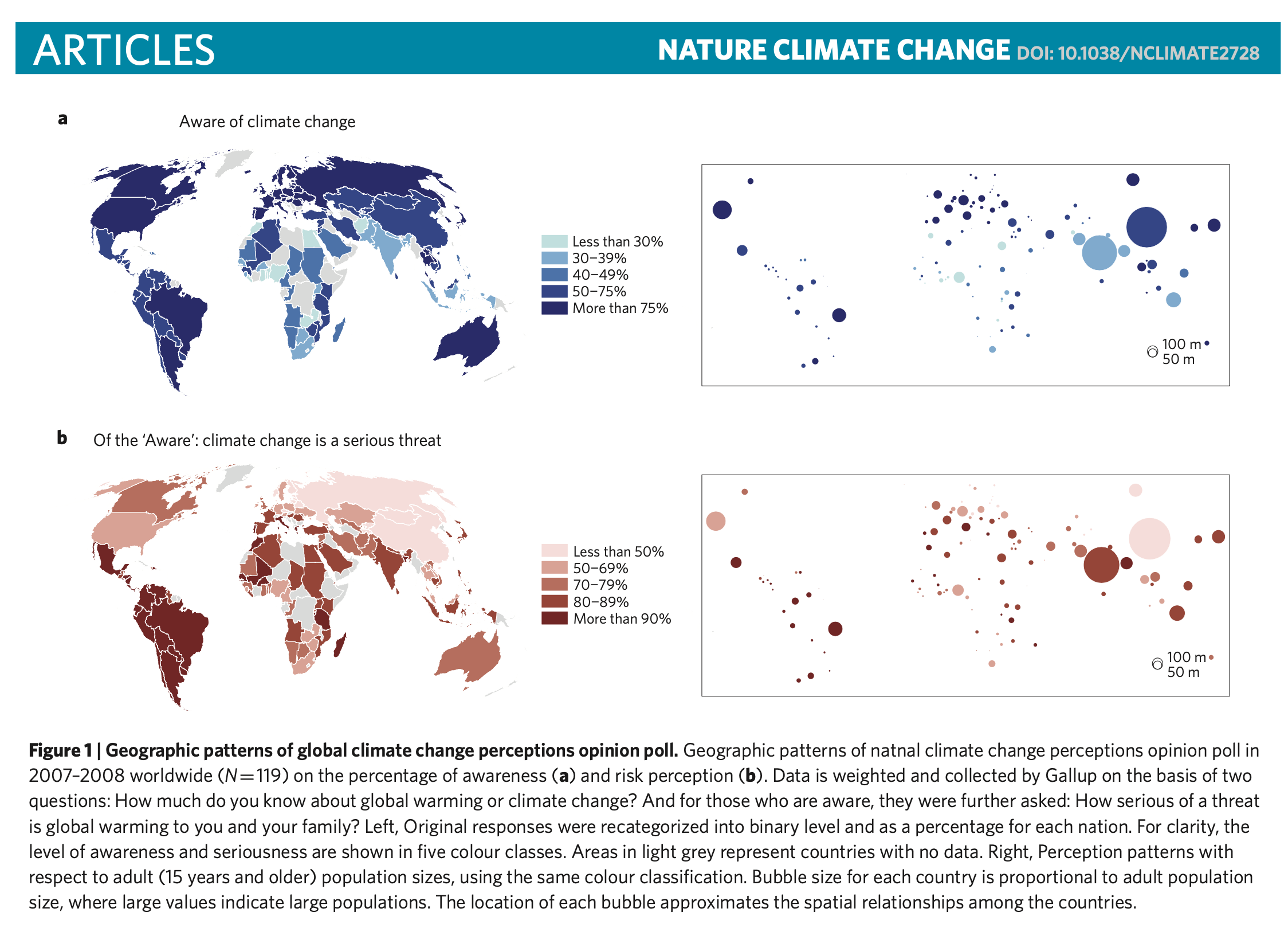

Here’s the global distribution of that awareness, as well as the distribution of levels of hazard perception, i.e. of those aware of climate change, who consider it “a serious threat”:

This visualisation shows that there were some parts of the world with deficiencies in awareness in 2007-2008. Awareness was low in parts of Africa, and South-West Asia. If you look at the right-hand side chart, however, which shows population size bubbles for each country – India and Indonesia are the only two major population centres with low awareness. So basically, across huge swaths of the planet awareness was already pretty high – above 50%, and sometimes above 75% in most of Europe, North and South America, and East Asia. From this perspective, awareness deficiency suddenly doesn’t look nearly as widespread or as serious of an issue. If anything, we could say that in 2007/8 awareness deficiency was a very specific problem for a few specific countries.

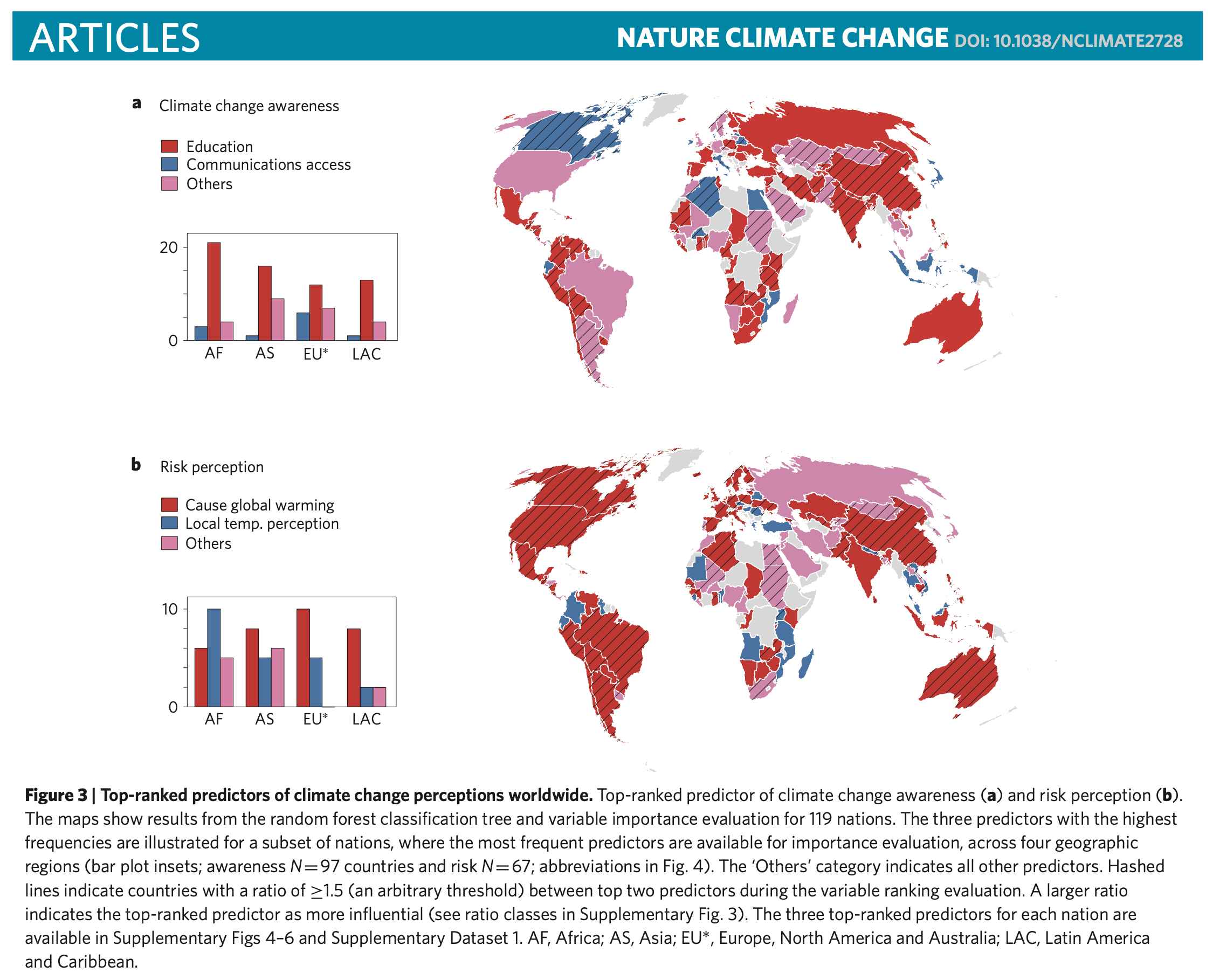

In the paper, the authors also cross-referenced other attributes of survey respondents to find out what the main predictors were for climate change awareness. Two issues stood out: level of education, and level of access to communication media. The greater your educational attainment the more certain it is that you’ve heard of climate change (which makes sense), and the same for greater access to media and communications, as it's here where we might expect most people to encounter climate communication.

So there were real inequalities in the distribution of awareness, but for much of the world, these come down to issues of educational attainment and access to media and communication. This is why the researchers emphasised in the 2015 paper that “national and regional programmes aiming to increase citizen engagement with climate change must be tailored to the unique context of each country, especially in the developing world.” There is no basis for blanket, one-size-fits-all approaches.

The researchers also looked at what factors predicted whether someone perceived climate risk as significant – that’s the bottom half of the chart above. The two main predictions for risk perception of climate change were a) a belief in humans as the primary cause of climate change, and b) local perception of temperature increase. That too is fascinating, because in the years since 2007/08 we have seen a steady stream of temperature records broken across the world. I am willing to bet that has had a substantial impact in the years since.

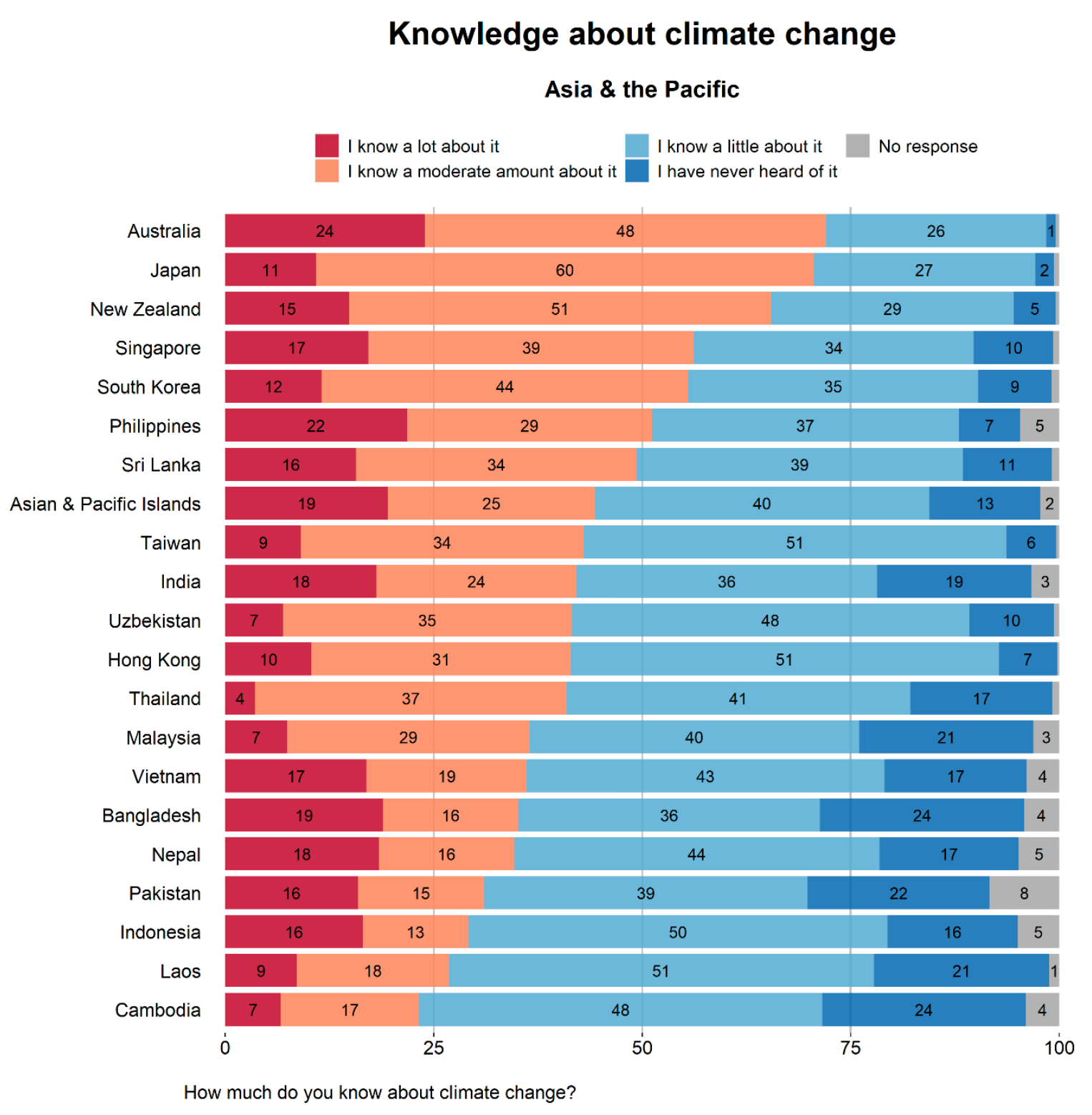

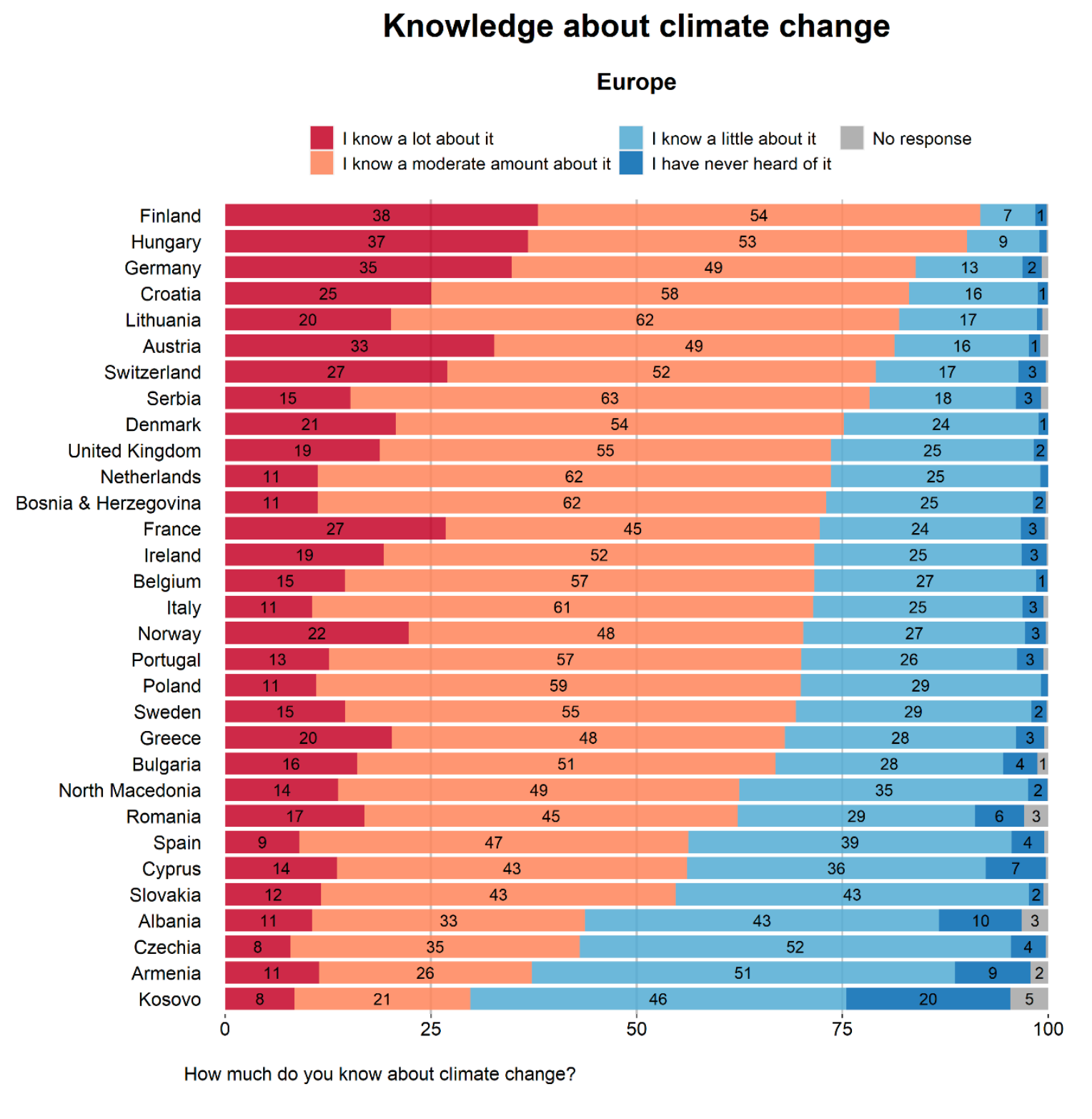

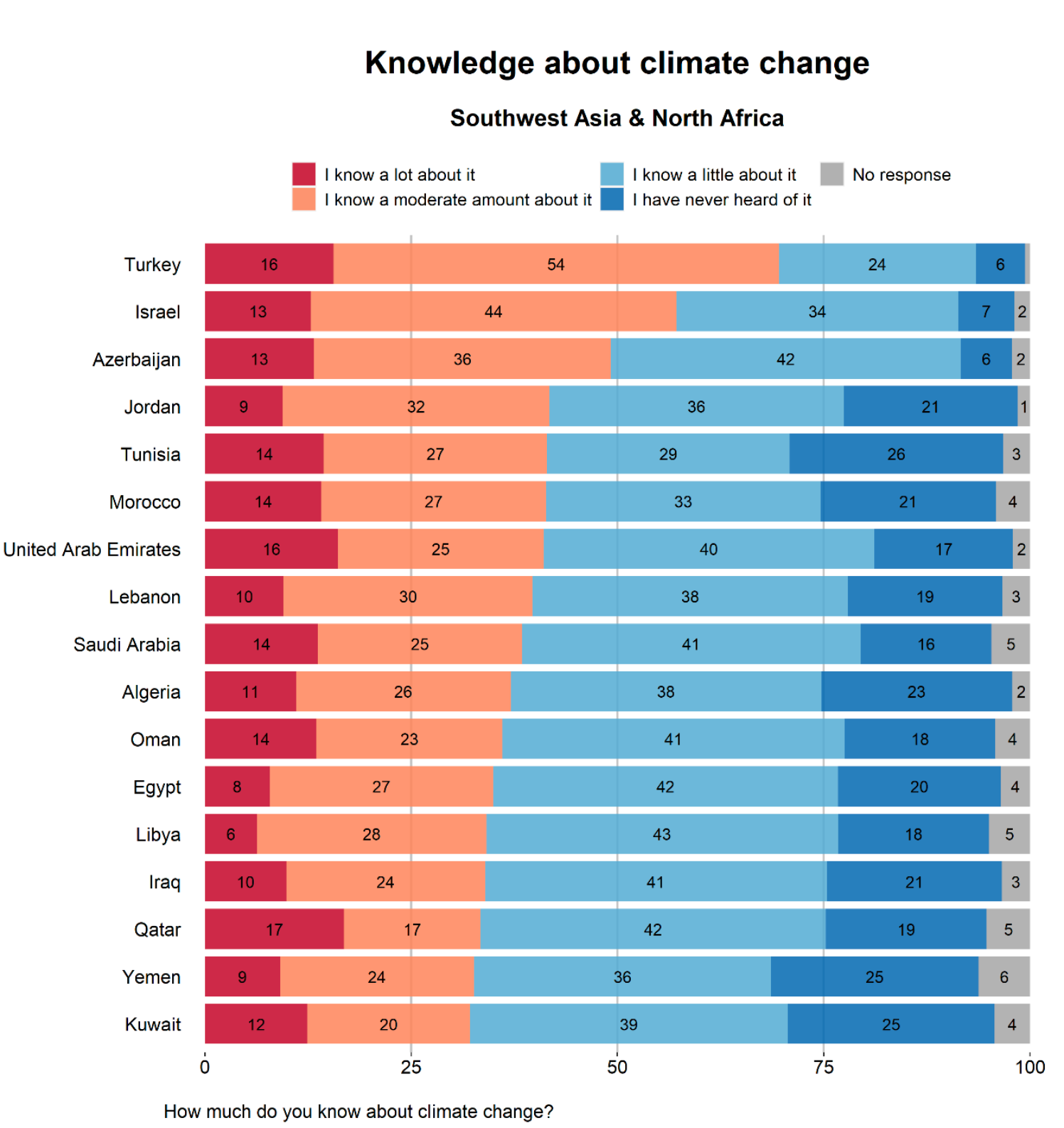

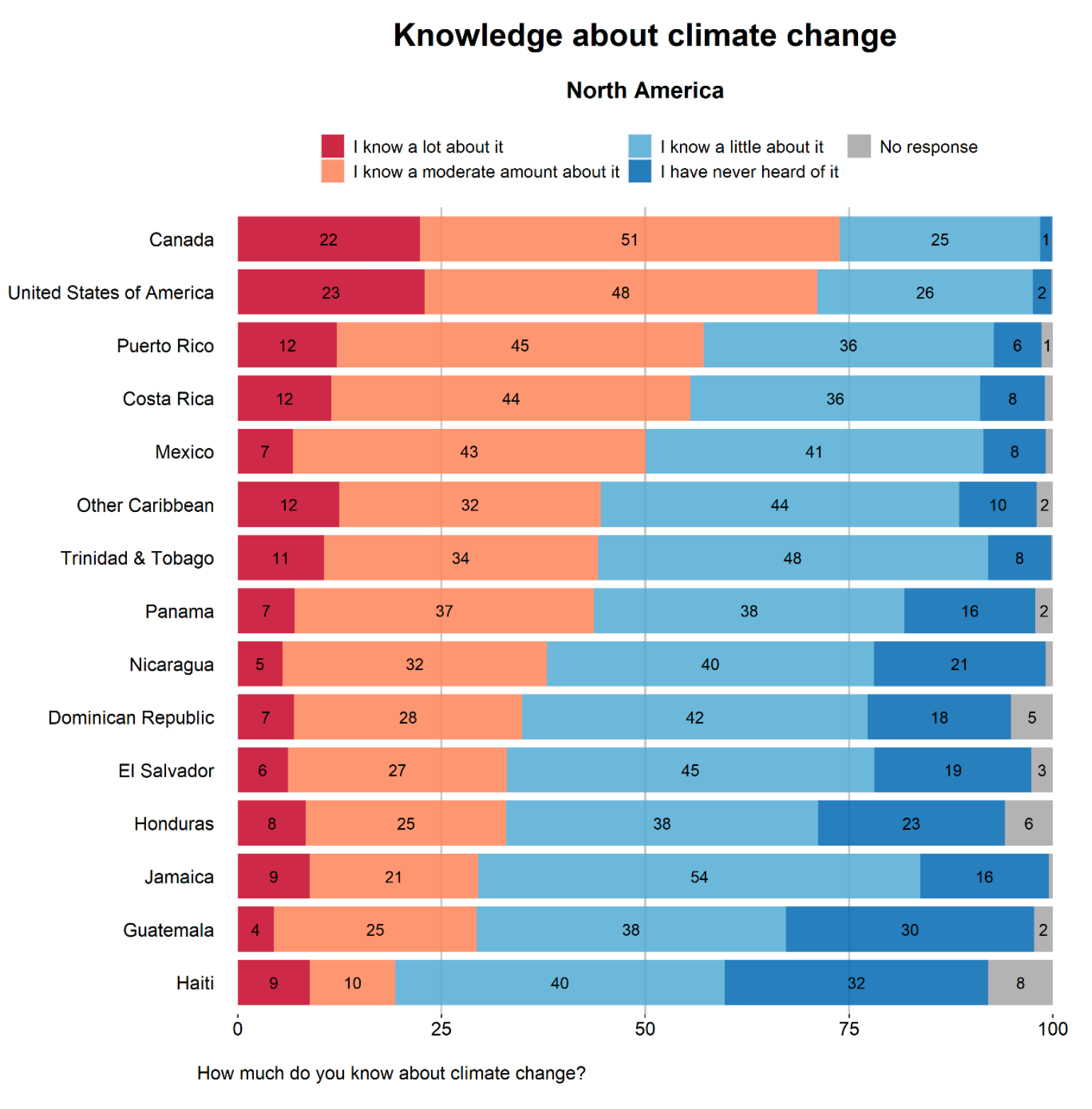

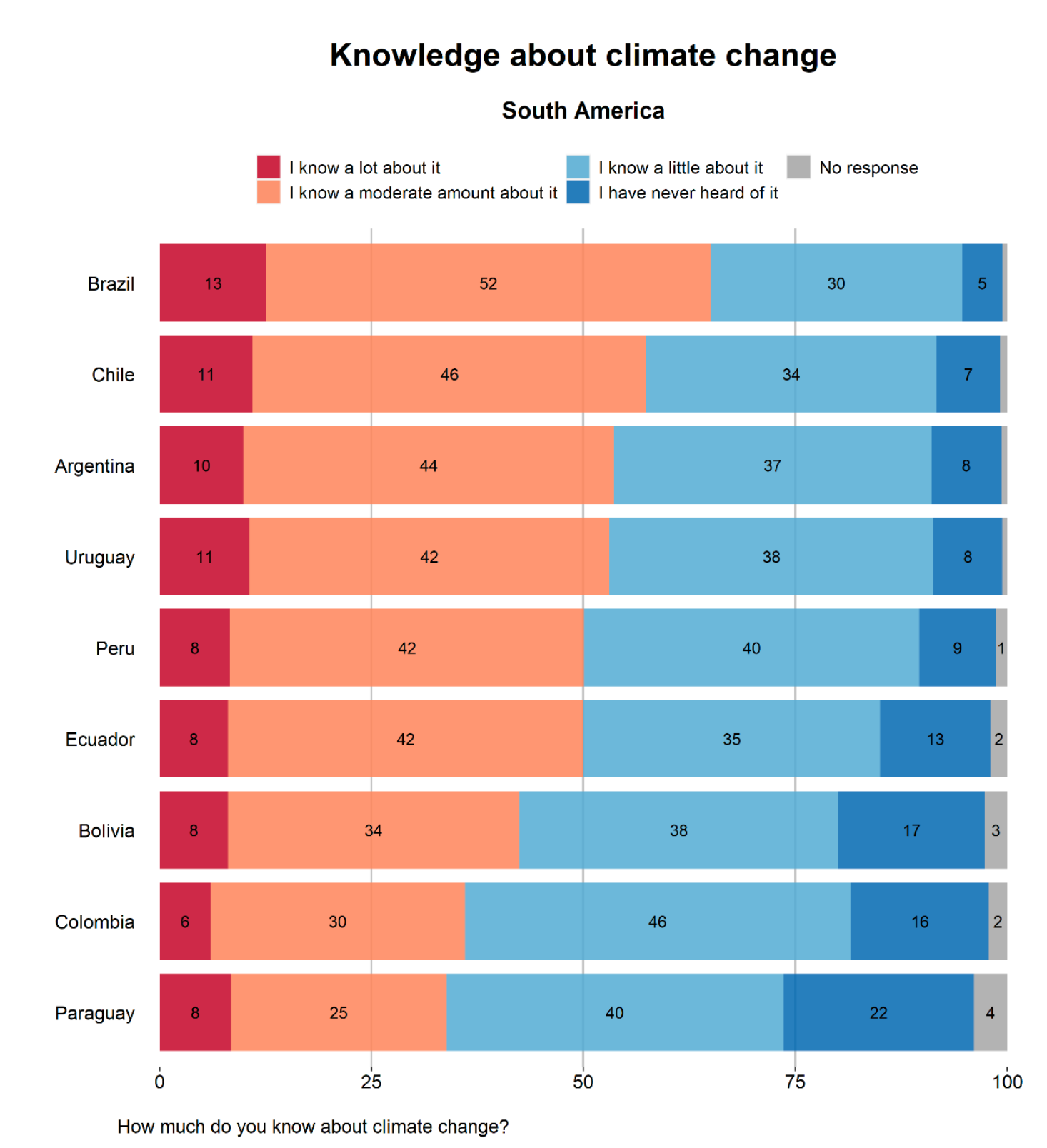

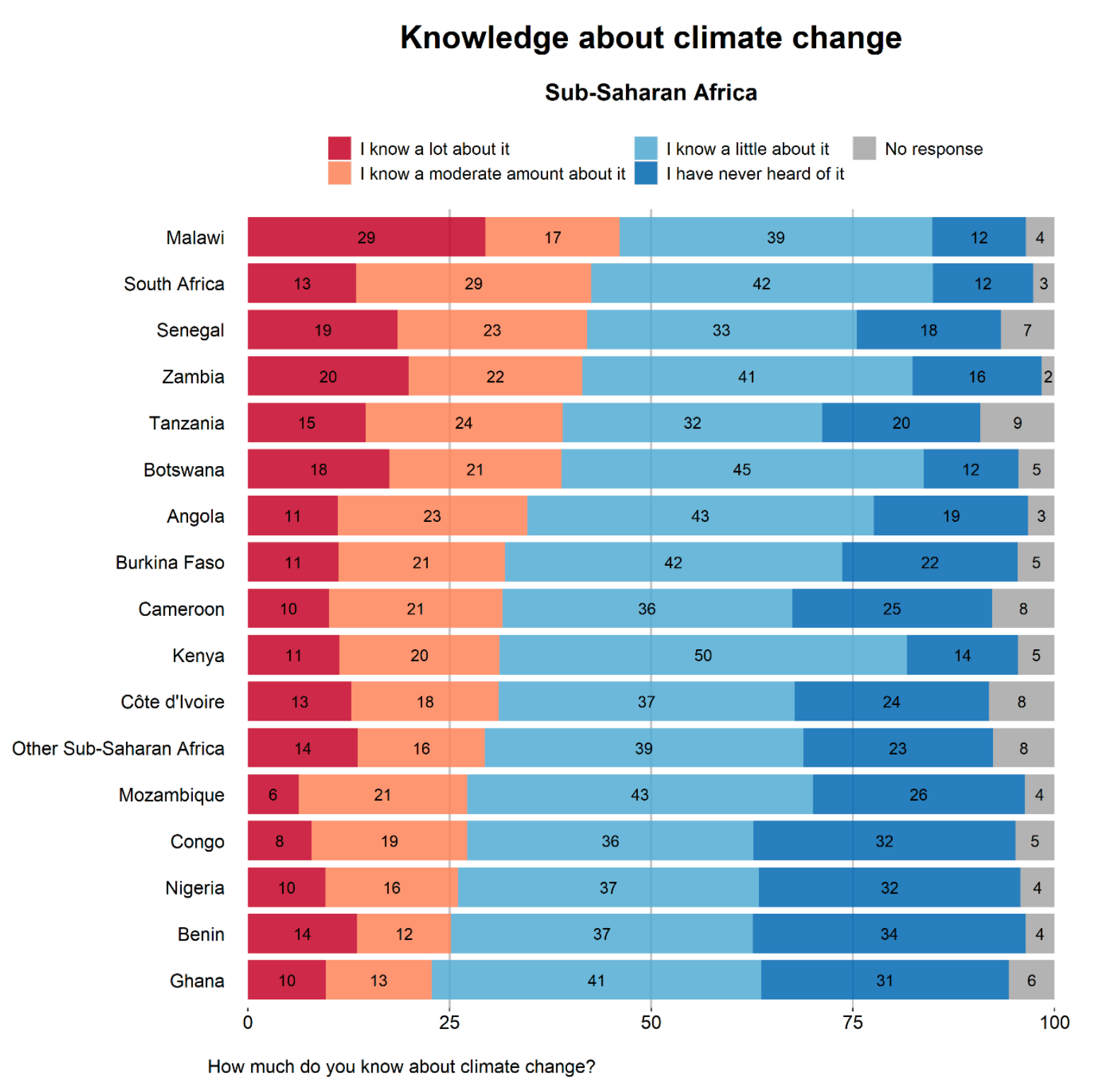

Which is what we see borne out in the most recent version of the study, undertaken in 2022 by some of the same research team, asking similar questions (though this time, conducted on the Facebook platform with the assistance of Meta) about climate change awareness and risk perceptions. What’s happened to the level of awareness of climate change in the fifteen years between surveys? You can see for yourself below, broken down by country and grouped by region. If we are looking to validate a ‘deficiency’ model of climate awareness – i.e. those who have never heard of it before – we are looking for thick sections of dark blue on the chart.

In almost all regions, a massive majority of people have at least “a little” knowledge about climate change – and at least in Europe and South America, majorities consider themselves to know a moderate amount about it. This is stunning progress. There is still a stubborn minority in parts of the world who have “never heard of” climate change, particularly in Africa, but even these are now commonly a minority and Indian and Indonesian awareness are supermajorities of 75%+ knowing at least a little about it.

Climate change awareness, at least in its most elementary form, is as ubiquitous as anything. Now there are a lot of people who only know “a little” about climate change – but that’s a greatly different proposition than the initial one which spelled out a lack of climate awareness as the thing stopping climate action. The latest awareness research findings represent what I consider a death blow to the simple form of the knowledge deficiency paradigm. If a super majority of people globally know even a little about climate change, and yet we are still struggling to enact the kind of coordinated global climate strategy and action that we know is so desperately needed then the awareness deficiency approach can't explain that. People do know about climate change now, even if only a little, yet that knowing has not translated (at least automatically) into the necessary actions.

So if awareness is not the problem anymore (if it ever was) then what is? I don’t have a nice simple answer I’m afraid. I strongly suspect that it will involve analyses of power and perhaps distributional conflicts (at the level of policy). But to bring it back down to earth, what does this mean for the games industry? A few conclusions I think follow.

Firstly, simple awareness raising needs to go as it’s not targeting the right problem. What do we replace it with? Is it a weaker, more contingent, or more targeted form of awareness? Perhaps. It’s almost impossible to be categorical. We need a more complex model of awareness and its relationship to action that understands the challenges individuals face in translating knowing into acting.

We also need to know what kind of actions we are trying to achieve – policy change? lifestyle change? among which audience? in which country? with what sort of game-related climate communication? The observation I made in chapters 2 and 3 of Digital Games After Climate Change was that we need to know precisely who we are communicating with, and that's hard to do in a way that flattens the potential of the 1 billion players in the gaming audience into a homogenous mass needing more "awareness".

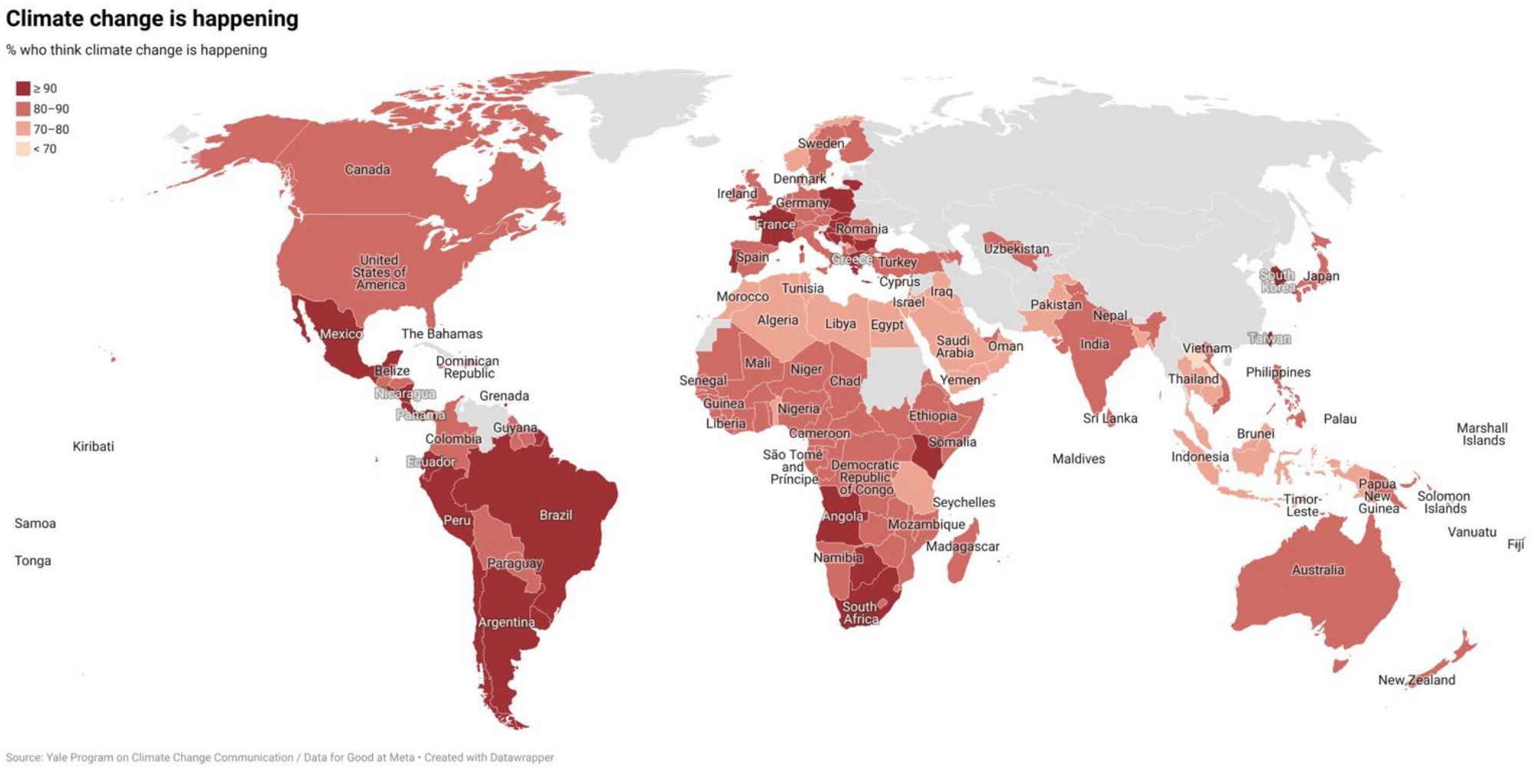

Secondly, the research exists now to guide targeted efforts at intervening in the perceptions of risk, climate prevalence, etc – the 2022 study has this fascinating map of the global distribution of the perception that climate change is happening:

Finally – if our problems are not “awareness” at all, if they are problems of power and distribution instead, then perhaps the most important conclusion is that we need to rethink the role that games play in modern power relations and, in particular, in relations to the distribution of resources. What sorts of material relations are our games enmeshing players in? Do we have the ability to suspend, or even lessen the material demands that game playing locks players into? Can we build climate justice into our software, not just representationally but materially as well?

At the very least, we know that a huge majority of people were aware of climate change in 2022 (and probably even more in 2024). As educational access expands, and as local temperatures increase around the world – that trend is likely to only continue.