Why do we care about sustainability?

Greetings, GTG readers – it’s Gamescom week, and everyone’s been busy looking at new game announcements, workshops and things like that. We (the SGA) ran a workshop at Devcom that road-tested some of our newest SGA Standard tools and got attendees hands-on with them to try and understand the impacts of their own travel decisions they took to get to Devcom/Gamescom, as well as the impact of digital downloads of games. My thanks to everyone who came out for it and helped test these tools, and hopefully left with a better sense of where to begin with sustainability in the games industry. This was just the first iteration, and we’ll run it again in other venues, guaranteed, so don’t stress if you missed it.

I wanted to write a quick, short reflection this week on the question in the title of this piece. It’s a topic I’ve written about before, approaching it through the lens of “climate advocacy”. In this piece, I want to think about why we care about sustainability at all. I think there’s an obvious surface answer, but there’s a deeper analysis I wanted to get to, which I started to grapple with while watching a very compelling video summarising some of the research around ideas like self-compassion, titled “how to take excellent care of yourself without being cringe.” It’s quite good.

I don't know if I answer the “why sustainability?” question in general; I think it needs answering individually. But maybe my reasons for caring about it will resonate with you and give you something to reflect on to help motivate your own efforts?

The first thing to note is that it’s not like sustainability is some eternal, immutable truth, some Kantian Good that floats freely in the realm of pure ideas. One of the most fundamental features of our human lives is that they are finite, whereas sustainability paradoxically gestures towards the infinite, the ongoing, and the perpetual. Perhaps the most appealing dimension to renewable energy is that it promises to be a virtually unlimited source – even if, in actuality, they too are limited, just in different ways. Renewables are limited in the same way as the sun is limited in the fuel it burns – from the perspective of a human life, it may as well be infinite. No human being will ever see the end of the sun with their own eyes.

Similarly, human life is not sustainable; we cannot eternally sustain ourselves. The body breaks down, wears out, and we die. Does this present a challenge to sustainability, particularly when so much of the worst of climate change will happen after our finite lives? Perhaps, though clearly, there is a lot to innately attach to in the renewability of human life by having children, passing on one’s ideas, leaving the world a better place for others, and other forms of expression of love for the world beyond us. But we also don’t have to have children to care about climate change, either.

The next thing I wanted to suggest is that (perhaps despite my outward appearance) I care about sustainability, not because of some intrinsic or dogmatic hatred of greenhouse gases in themselves. There's a disconnect between what has to be the objects of our effort and attention (GHGs) when we work towards sustainability, and the final object of care driving why we do this work. Carbon dioxide, despite its reputation, cannot meaningfully be described as “evil”, or even as “undesirable” on its own – we might as well direct our ire at the sun for coming up every day. In a very particular sense, these gases we are trying to control simply are. They are completely amoral in the strictest sense. They belong to the realm of real, existing objects, the universe of things that are not us. In a way, the human realm of moral judgment is something imposed on top, reflective as much of us as it is of any real state of affairs.

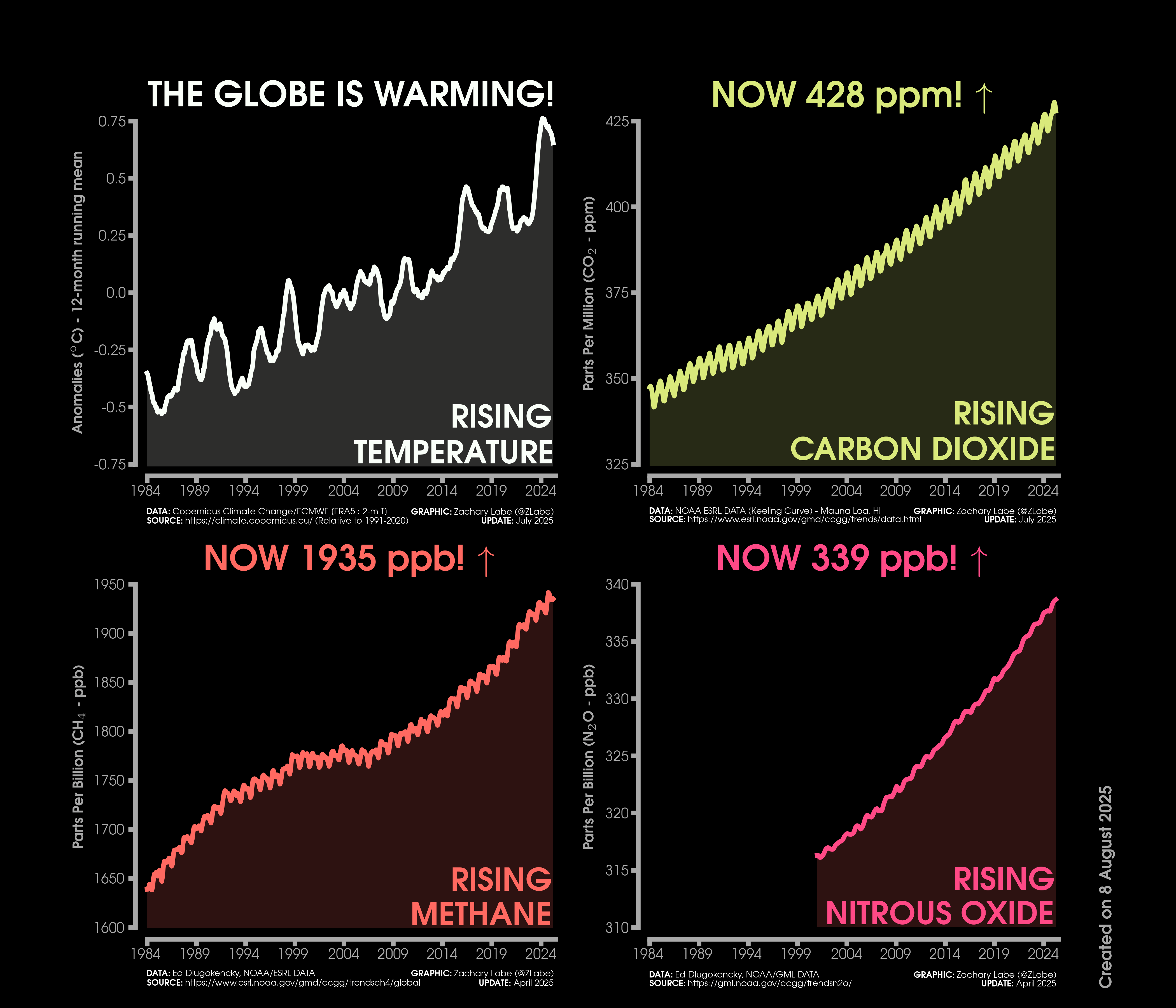

What I care about is not carbon dioxide – it’s what carbon dioxide does, what it’s going to do, and, crucially, what it is going to do to people. It’s the effects of this ubiquitous, naturally occurring gas, and what it means for us to have the parts-per-million concentration on an ever-increasing trajectory.

It’s because I know what these lines trending upwards will mean for people all over the world that I am so alarmed by the release of carbon dioxide, why I am dogmatic and absolutist about the necessity of phasing out the use of fossil fuels. Because it means the end of entire ways of living.

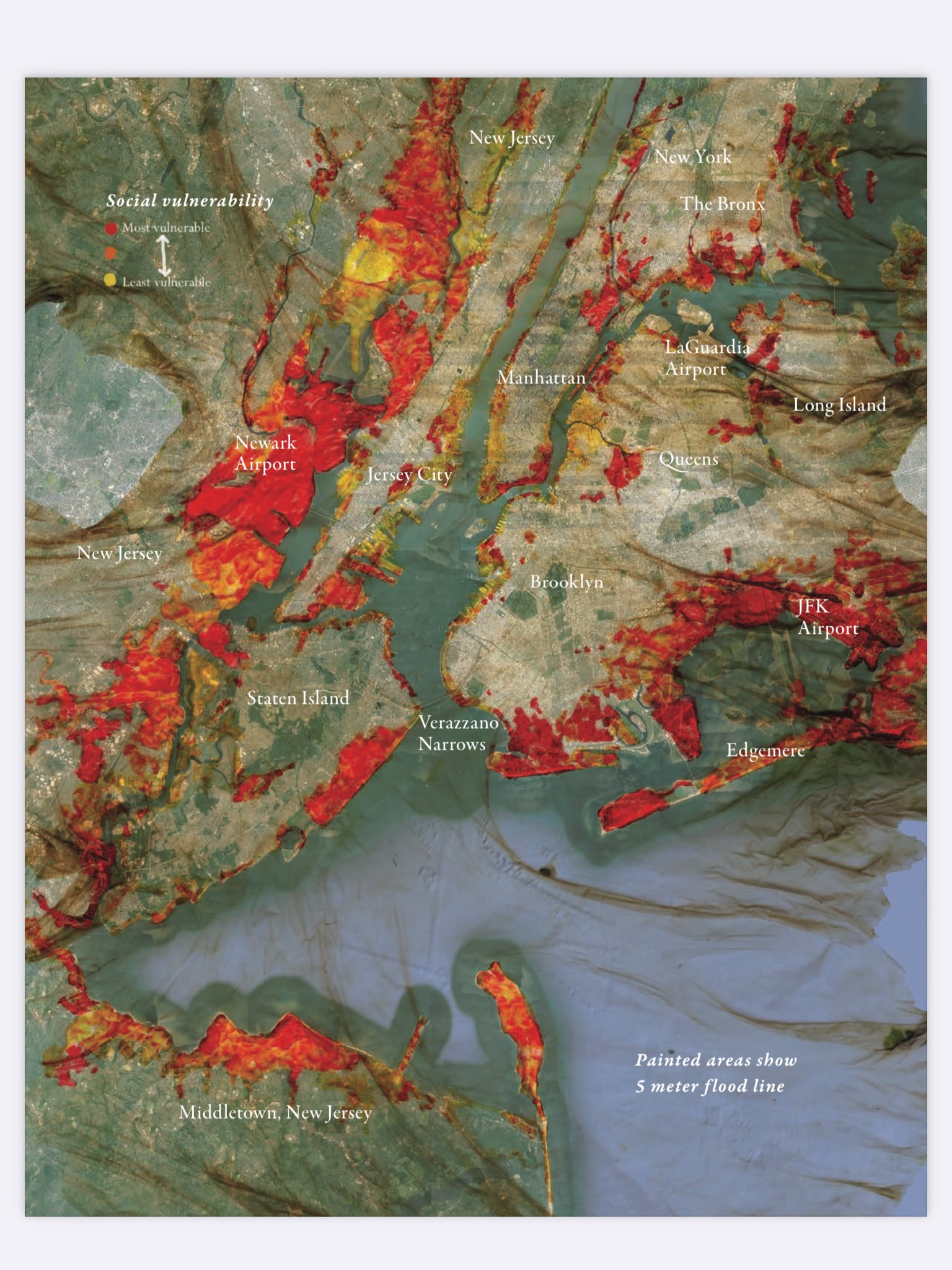

It means coastlines are going to be redrawn; it means large parts of cities in flood-prone areas will become virtually uninhabitable. It means some people dying premature deaths thanks to heat waves (175k in Europe annually already), or to being caught in fires. It means people catching tropical diseases that spread to areas they’ve never been seen before – like dengue fever coming to Britain.

I don’t think I need to labour this point, but I want to recenter the effects on people as a central, motivating and sustaining force in my (perhaps our) sustainability work and thinking. It’s worth returning to now and again.

And it’s not just people who are harmed by the effects of these quantitative changes in CO2 concentration. There are trillions of plants, animals, and other branches of the tree of life out there that are more or less exposed and vulnerable to climate change than humans are. Some of the largest forests in Australia are projected to lose 9% of their trees for every degree of warming that this increasing concentration of CO2 produces.

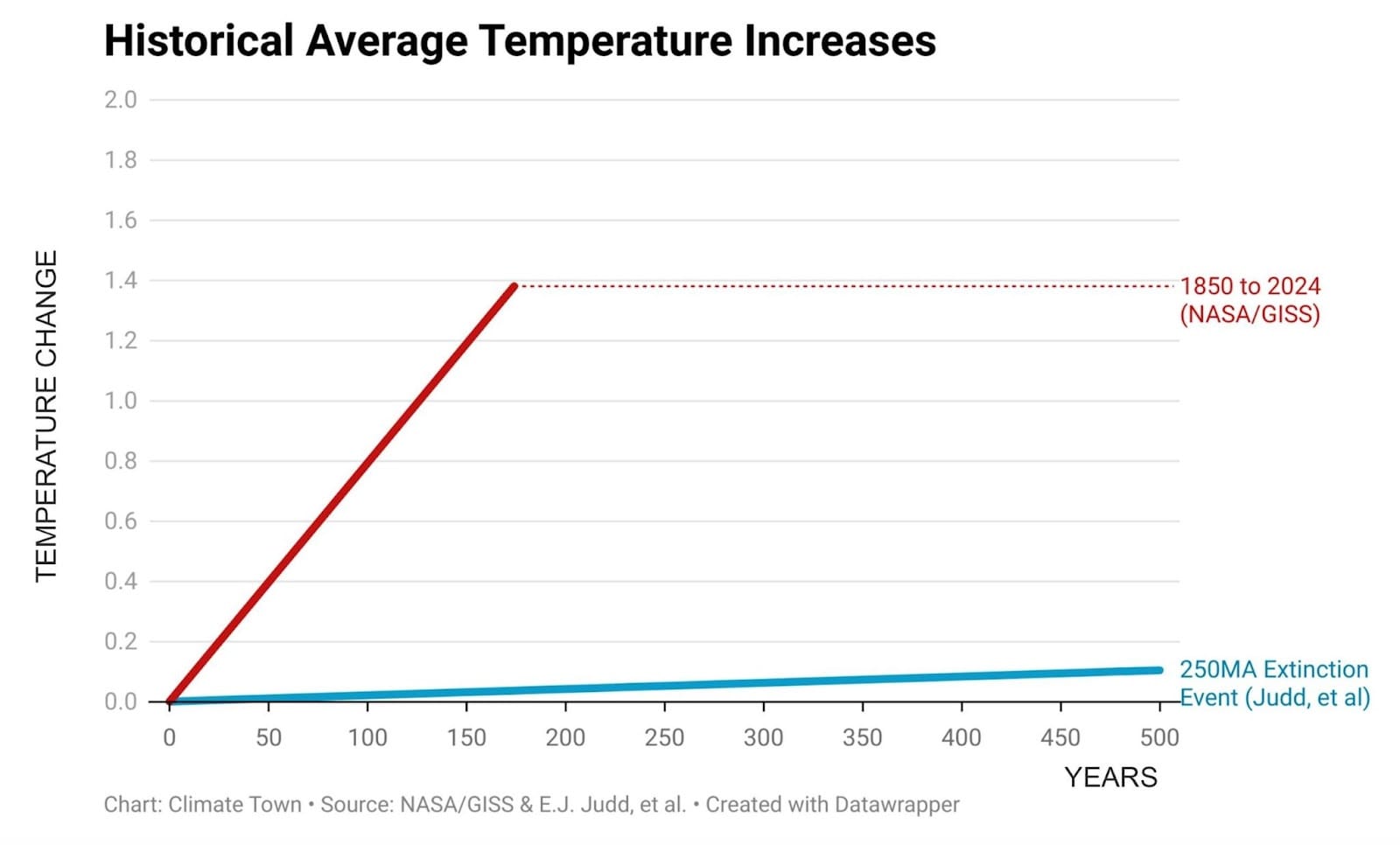

The Climate Town youtube channel recently made a dramatic graph comparing the pace of temperature change in our time compared to the change over time during the last great extinction event on Earth. It’s a dramatic and sobering illustration, if you allow it to be. We are compressing thousands of years of change into mere generations of human lifetimes. How can the rest of life on planet Earth cope as well as us, the most adaptable species the planet has ever seen? I fear for the orangutan's and all the big cats, and all the shiny beetles and even all annoying tiny midgey insects. It's heartbreaking to contemplate the rate of extinctions we are responsible for.

Even if you’re not a natural tree-hugger, and you don’t find yourself immediately drawn to care about trees and plants and animals, care for non-humans can arrive through values that are entirely people-centred. Human society is downstream from all of nature. It can't exist without it. We depend on it not just for food, but also for shelter, for the hospitable environment we enjoy, for the predictable water cycle and precipitation, even the cycle of photosynthesis that underpins human respiration. All the oxygen molecules we breathe today were at one point split from their carbon molecules by prehistoric and present-day blooms of plants and cyanobacteria.

For myself, I try to maintain an approach that also values nonhuman life, if not necessarily equally with human life, then at least on its own terms, and for its own sake – appreciating it in particular for its difference from human life. It’s not something I refer back to much in my day-to-day, but the reading I did for my PhD in human and non-human philosophy was extremely formative in this way. It motivates me to uphold sustainability for its centrality to the conditions that gave rise to all these amazing things around us. It’s what I love so much about Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t and his field trips to look at plants I'll never appreciate with even 1% of the ferocity and understanding he does. I love seeing plants through his eyes, and hearing him explain their irreplaceable relationship to place and time, their evolutionary history.

I imagine (and hope) that it’s also possible to care about sustainability purely out of love for the games industry as an extension of human culture, and quite realistically a pinnacle of human civilisation. Games are an incredible marriage of human artistry and the awesome powers of modern material science, but video games rest atop a fragile pillar. They depend upon the continuation of a certain standard of living, certain material realities that we are fast running up against the limits of. When I wrote Digital Games After Climate Change I thought that the most serious risk to the games industry would be an authoritarian climate regime that takes charge of energy systems and declares videogames ‘nonessential’, redirecting human labour and flows of energy to essentials. It may still be. But the more pressing challenge might be to the standard of living that supports the vibrant, innovative games industry we have – whether that’s the erosion of purchasing power of the mass of the world’s people via extreme inequality (disposable income is the engine of games industry) or via disruptions to power systems, or worse via massive flows of climate migration, or some other physical disruption. The coming decades are likely to be a hard test. I’m not entirely confident in the leadership of the games industry these days. Though, as always, faith in the ordinary worker, the rank-and-file members of our much neglected institutions for collective power and preserving our own interests is never truly misplaced.

Lastly, there’s always the appeal to self-interest – climate change is coming for you and me too. Even the billionaires and their bunkers in New Zealand are far more exposed to climate change than they imagine, as has been well documented. The resilience of economic and social systems is not a function of how much money is invested in them (though it can certainly help) but in how much ordinary people are behind them, and make them work. This much I learned from my relatively brief time in the NTEU, and there really is no such thing as “the union”, there’s really just us, together, for better and for worse. Hell may be “other people”, but they are also the only real salvation we have.

So sustainability is other people. It’s you and me, caring enough to put our shoulders to the cart and give it a push. It's the hope and expectation for better things, for renewal, its doing something because it needs doing, because we care about people.