Can we put a number on the game industry’s annual GHG impact? Part 1 – Game Development

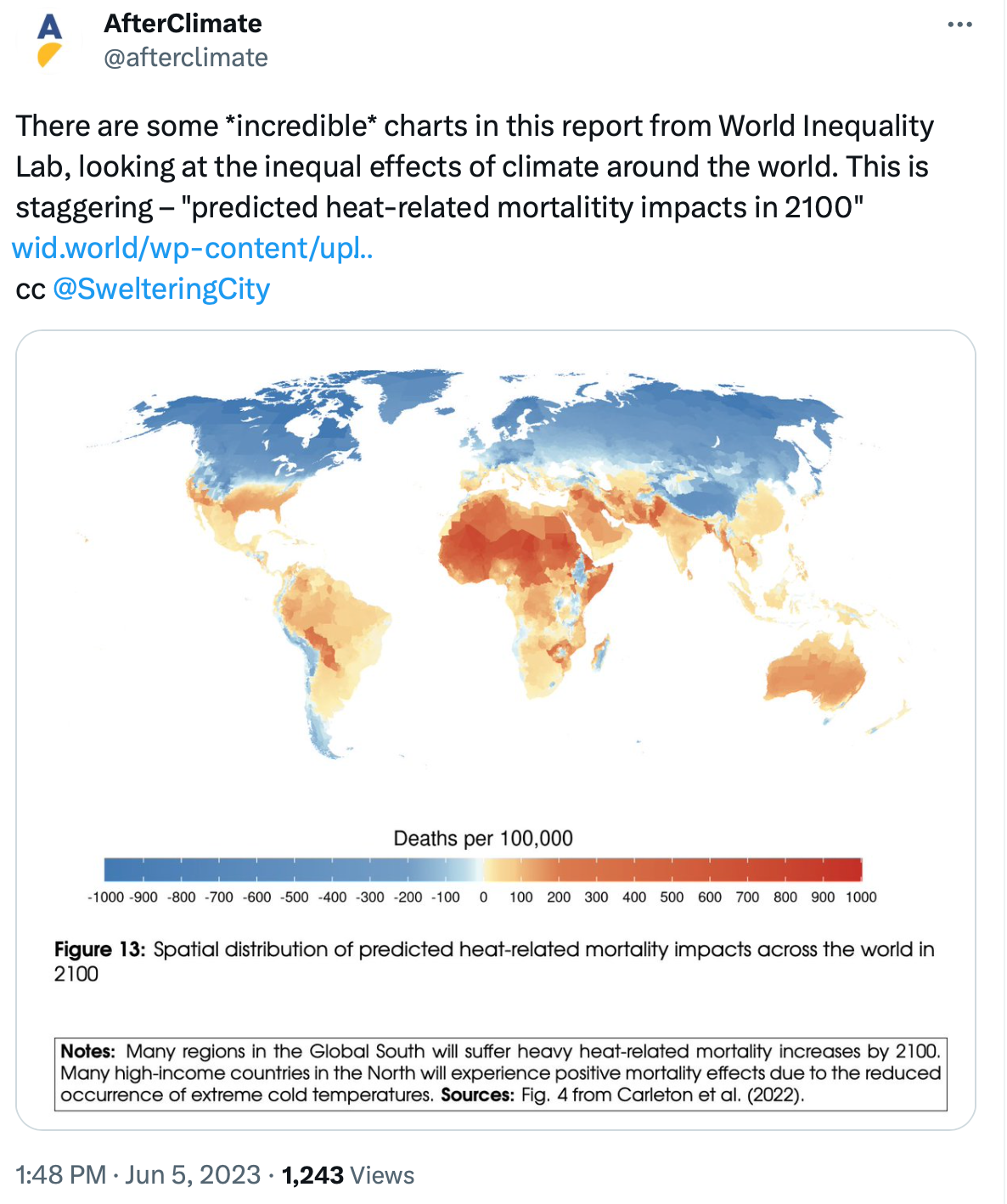

This week saw World Environment Day, and lots happening to mark the occasion, from the Green Game Jam voting to the State of Green Software report. I spent the day digging into another great report on the shortfall in climate funding for the most exposed (and least responsible) parts of the world.

It was a timely reminder that those of us who can act on emissions abatement and adaptation absolutely must. I haven’t even begun to think about what the games industry might do to support climate adaptation, but I think there’s probably some potential there.

But before we get to adapting to a climate-changed world I feel it’s strongly in our interest to prioritise mitigation first, or at least, ensure that adaptation efforts do not come at the expense of mitigation. This is why I am so obsessed with emissions numbers, methodologies for calculation and attribution. I don’t have any hard evidence for it on hand, but if it follows similar preventative dynamics (such as preventative health and other interventions) then $1 of mitigation will be far more effective than the same $1 spent on adaptation. Not getting the hole in your jeans in the first place is always cheaper than fixing it, or worse, replacing it. And there’s obviously no replacing the earth’s climate system. That said, ‘mitigation’ does not mean loading up on carbon offsets either – it means finding ways to prevent CO2 emissions in the first place.

Back when I first started giving talks about the emissions data and calculations I made in Digital Games After Climate Change, I was asked by a member of the audience at my GDC talk whether I could give a single number that is the global carbon footprint of the digital games industry. Having been so deep in the weeds at that point, grappling with so much detail around particular parts of the games industry, and wrangling the complexity of emissions calculations and uncertainty (I look back on that it now and think: I was just a tiny baby, there was so much more to learn, there still is!) that it hadn’t even occurred to me to add all the numbers up. In hindsight, it’s sort of the obvious thing to do: take a step back, add everything together, and go that’s it, that’s the number. But thinking about it immediately afterwards, it wasn’t even obvious that I could just do that, even after years of working on it.

At the same GDC, I heard about a project one of those climate NGOs was apparently doing to put a figure on the whole games industry and its footprint, so I figured I’d wait for the results, and see what comes out. Maybe we could compare notes! But that was over a year ago, and I haven’t heard anything about it in a long time. I can only assume it didn’t end up happening, which is a shame because having a sense of the scale of the problem is critical to appropriately calibrating our responses.

Recently though I was chatting with Lucas Joppa about this. If you don’t know Lucas, you absolutely should – check out this really interesting interview he did with GreenBiz, on his ambition to make net zero standard operating practice. It's good stuff. I did some back-of-the-envelope sums for him, just pulling together the data I had on hand that gave a sense of the scale of emissions. It’s close to approaching the full figure, but it’s not quite what I was asked about last year. Still, I wanted to share it here with GTG readers, talk about the current data gaps, and what we might need to get a clearer, more definitive picture. It’s the sort of thing I’d love to work on, so if anyone has (or knows of) some grant money to facilitate it, please do put me in touch.

In DGACC, I broke the game production process down into four stages. These stages don’t exactly correspond with the GHG protocol standard, which is designed to allow discreet businesses to account for and disclose the GHG emissions they are responsible for. But its focus is not on calculating sector wide emissions, and as far as I am aware there aren't any particular methods for something like this. So I did it this way for expediency, and because I think it’s necessary to achieve a comprehensive measurement of the whole industry – there are simply too many individual companies, and too many companies still not calculating and disclosing their CO2 emissions. See the 2022 Net Zero snapshot for an indication of who is still lagging on even the most basic accounting – though some have begun to this year (and we're not too far off the 2023 snapshot now).

The four ‘phases’ of game production I looked at, each receiving an entire chapter’s worth of discussion in the book, were:

- Game Development

- Game Distribution

- End users (players & play)

- Game hardware

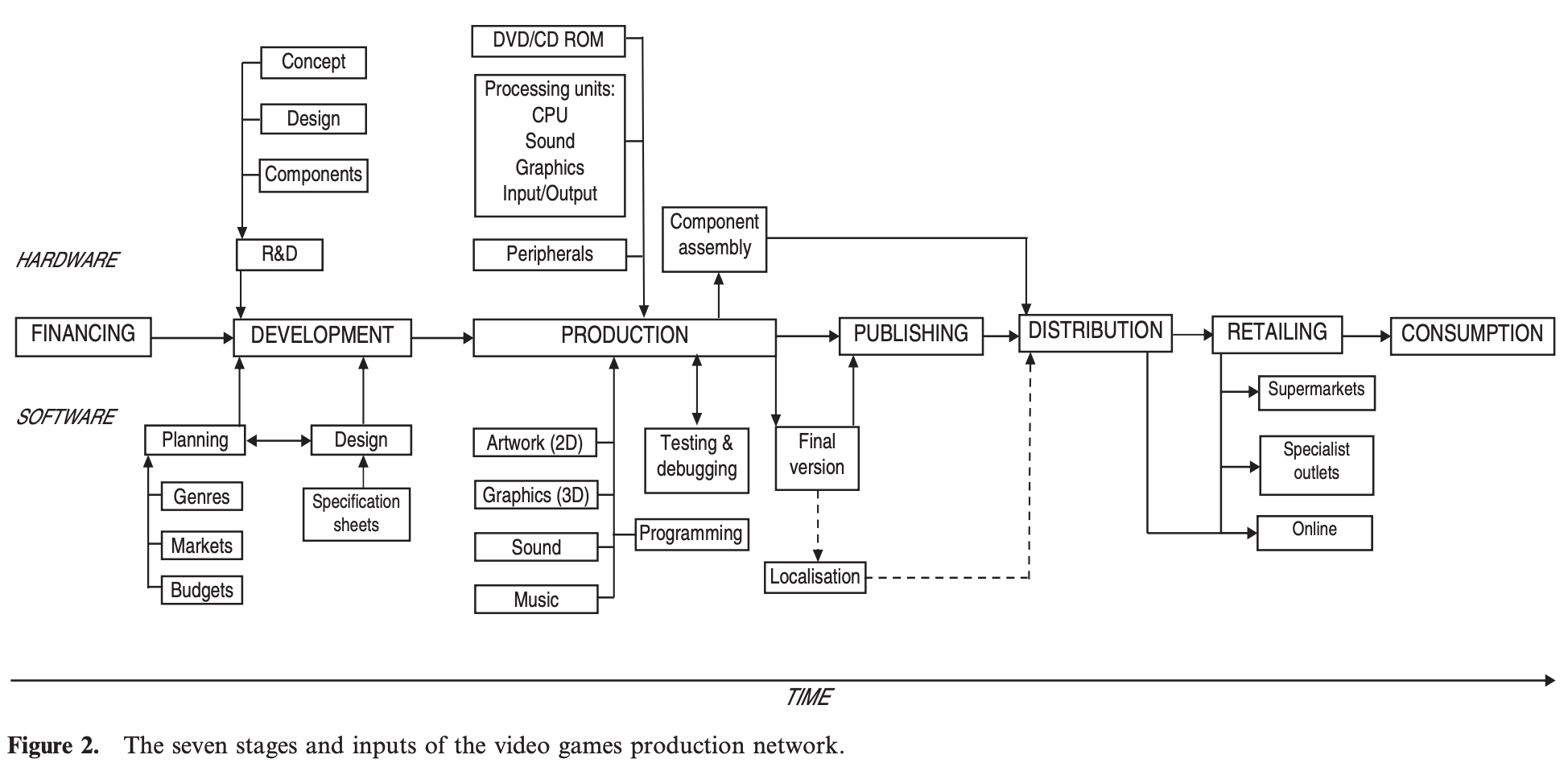

There are limitations to this approach – where, for example, do publishers belong in this? Who counts as a game developer? Do we even have accurate worldwide stats for how many game devs there are in the world? (Spoiler: not really!) Still, it’s a way to compartmentalise some of the sprawl via a simplified version of the model of the games production process, like the one shown by Johns et al. (2006):

In this post, I’ll go over the game development stage of the game production process, how I arrived at my numbers, and what data sources we have (and need better ones for).

Game Development

Back in 2020, it was hard to find good quality carbon disclosures – and when I did, they sometimes had mistakes in their early disclosures (we all do it!). It was also pretty exclusively large companies that were disclosing, and small to medium studios are an increasingly important part of the landscape.

So I surveyed game devs in early 2020 and got around 30 responses from around the world. I asked for data on the electricity and gas (if applicable) their studio/workplace used and combined that with the disclosures from CSR documents from the (few) game companies that were disclosing for that year. I compiled that into this table.

Again, some limitations: Sony’s figures are for the entire company, which includes the entire TV and appliance manufacturing parts of the business, and almost certainly is not directly applicable to game makers. Also, WFH solo game devs had higher (apparent) energy usage than workers in small studios, because on the same electricity bill as your “work” power use is also your fridge, your hot water, your TV, and all the rest of your home. So they’re not exactly indicative either.

But aside from those outliers, there’s a pretty manageable spread of energy intensity at game companies of different sizes. Most are somewhere between 0.4 and 3.8 tCO2e per employee – call it 0.5 and 4 for neatness’ sake, since we’re rounding for estimates anyway. Those figures also only consider the reported Scope 1 & 2 emissions these companies are measuring – for most, there’s no “end use of products” (scope 3, category 11) emissions in these figures, and only a couple (Ubisoft & Space Ape I think may be the only ones?) have regularly included the footprint of upstream Scope 3 (goods and services these companies purchased).

So it’s essential to keep in mind that we’re starting from an underestimate. It’s also a small sample (we have more data now that I didn’t have access to back in 2020) but the fact that there’s a reasonable cluster around those figures gave me some confidence that we have at least a ballpark to play in, other caveats aside. Subsequent years of ESG reporting have not radically departed from these figures, either.

So we can guess that each game dev is probably responsible for at least 1/2 a tonne up to as much as 4 tonnes of CO2 per annum through their work – and influenced quite a bit by where they are in the world and their local grid CO2 intensity. So we just need to figure out how many game devs there are in the world, which is not easy. In the book I compiled as many different national industry sources as I could find, including some from Aphra Kerr’s ‘Global Games’ book, which had some figures for pre-2017, and which I scaled up according to some growth rates for the industry. There’s also an unknown number of student and hobbyist developers – I was unsure whether to include them in the overall figure. I found one historical figure for the number of registered Unity accounts at around 4 million (!!) which is a lot, but would include quite a few of the aforementioned professional developers.

Here’s my conclusion from page 115 of Digital Games After Climate Change:

We’re left then with either a conservative figure of around half a million directly employed game developers worldwide (most likely an undercount) and perhaps as many as 3 or even 4+ million direct and indirect workers, such as those on contracts, freelance, self-employed and other workers peripheral to the industry (and which might risk stretching the applicability of our identified emissions profile).

As a result, and given our earlier CO2 range of the average game developer (p.116):

we might figure that a reasonable estimate of emissions is somewhere in the range of 1–5* tonnes of CO2 equivalent per employee per annum. To produce our estimated footprint we multiply this range with the number of employees in the global games industry. Starting with the conservative end of our estimate—this works out to be a range from 0.5 million to 2.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

If we tentatively, and at the risk of introducing inaccuracy, count the global games industry closer to the 3–4 million figure (or even more), that shifts our figures to a range of 3–15 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions per annum. We could also update the number of gamedevs to reflect the number in 2023 – I haven't even tried that, but I reckon there's probably more today than there was in 2019/20 (the year this data reflects).

And remember, this is only Scope 1 & 2 – parts of Scope 3 (downstream) appear later on when we look at end users. Upstream Scope 3 is not even really in this picture yet. That’s big-ticket CO2 intense items like flights and travel, and all purchased goods (like IT equipment) as well as services (like data centres). Because Scope 3 is an optional reporting category in the GHG Protocol, some companies are still not reporting even partial Scope 3 data, which is a real shame. Responsibility for these emissions really is shared, as it’s nearly impossible to neatly split up, for example, emissions in data centres. This is because “operational control” (one organising principle for the GHG protocol) is also shared. If you are a big company that rents a lot of computing in a data centre, you have some control over the emissions – you could use less compute for instance, or improve your software efficiency. But the sourcing of the energy for that centre? That’s not really up to you – and unless you are a really big customer you’re not likely to have much of a say over it even if you want to. Scope 3, up and downstream, is the hundred-pound gorilla in the room, and it’s not going away any time soon. Its anywhere from 80% of the disclosed emissions on a per-company basis, all the way up to 99% – a lot of that is gamers, however, and we will do some accounting for them elsewhere.

Interestingly enough, Ubisoft has taken a bit of a unique and incidentally helpful approach in its recent CSR documents where it includes upstream (and only upstream) Scope 3 – and while it would be more ideal to include the huge part of gaming emissions which is end use of sold product (Scope 3, Category 11) it’s incidentally beneficial here, as it gives us a rough sense of what we might expect if we added back in upstream Scope 3 to the above figures. Remember this is to avoid double counting end-users later on (since we will take a different approach there).

Ubisoft’s upstream Scope 3 was 87% of its total footprint in 2021, so that range of 0.5-15 million tonnes, we can multiply by 7.6 to get a (completely fanciful! entirely estimated! but not flagrantly impossible either) upstream value chain estimate for game development activity of 3.6m to 114m tonnes of CO2 per annum. (!!!)

Okay so through the power of multiplication and guesstimates, we’ve ended up with a plausible range that crosses three different orders of magnitude, which is... not as helpful as it could be. I’ve got some ideas for how to clean that up and arrive at a more reliable estimate – but it’s going to have to wait a few more months until the rest of the games industry wraps up its 2022 emissions reporting.

Keep in mind too that scope 3 figures involve a shared responsibility across the value chain. It does slightly stretch the definition of “the games industry” to encompassing within it parts of the footprint of airlines, data centres, IT hardware manufacturers, and so on. But the games industry probably can't do without these services either. Does it have full and sole responsibility for them? Probably not, but they are within the value chain – the industry's sphere of influence clearly extends acoss a lot of emissions. This could be a good or a bad thing, depending on how proactive, creative and determined to do something the games industry gets.

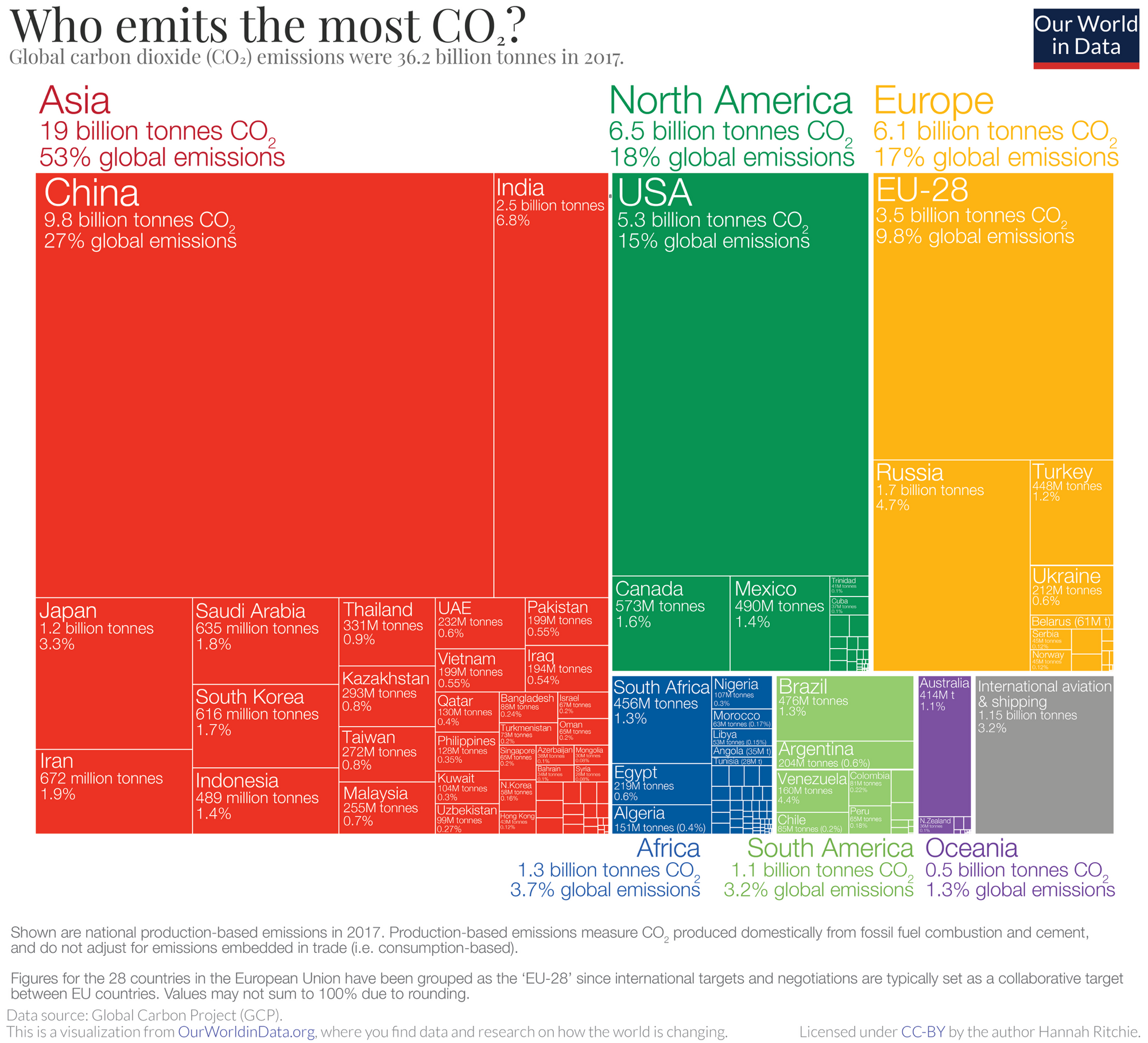

Regardless of where we draw the boundaries for responsibility, if it’s even close to that top-end figure of 114 million tonnes per annum that puts just game development and its value chain in the range of some entire countries annual emissions. Countries like the Philippines (128M tonnes), Kuwait (104M tonnes), Nigeria (107M tonnes), and above countries like Chile (85M tonnes), Columbia (81M tonnes) and Bangladesh (88M tonnes).

It’s probably not quite that bad as the worst case scenario either – I certainly hope it’s not. There might also be a temptation out there to dismiss an emissions figure as big as some countries as being improbable, even impossible, especially given that it’s just the upstream part of the global games industry. But I think it’s also worth reflecting on whether that reaction is justified. The games industry is more than happy to embrace its big footprint when the impacts are positive: from the billions of players that are “reachable” through games, to its billion-dollar economic scale and benefits. We shouldn’t shy away from this.

As I say, I hope it’s not as bad as this, and that at least seeing the process and steps I have taken to calculate the possible range of emissions for just this part of the games industry is illuminating. These figures will always be open to challenge and revision, with new and better evidence, and I hope we can get better direct data to start filling in the gaps. If there's someone out there tracking games employment figures globally, or a source with better insight on value change emissions, I'd welcome the input.

Later this year when I’ve compiled the data for the 2023 snapshot I should have a little better sense of how close these figures are to the disclosed emissions from many of the biggest game companies in the world. If they add up to much less than this top-line figure, then we will start to hone in on where in the range is more likely. Maybe it is as low as the bottom end figure. We'll have to wait and see.

There's also the potential to further clarify the intensity of different scales of game production. This would involve answering whether CO2 emissions per employee scales linearly or exponentially with the size of company, or if some other dynamic is at play. Perhapts its about the type of game being made. Maybe mobile game development is also much more carbon efficient than AAA console and PC development. We just don't know (or if anyone does, they're not telling!). There's also potential to look at the concentration of game developers in different countries and parts of the world to improve our estimates – the emissions factor of electricity used in Montreal is a fraction of what it is in Austin, Texas for instance. And Australian game devs really do have to fly a long way to get to anywhere central to the games business.

We could also try and peer back through time to make some estimates about the cumulative emissions for this part of the games industry. We would need to be willing to accept more guestimates, because unfortunately there's really not much data to go on prior to 2019, but it could be possible. We could apply some sort of curve from today back to its inception, which could tell us how much the games industry has contributed to global heating over time.

I suspect the more important question to ask is have game industry emissions peaked? With nothing more concrete than my intuition based on the way things are trending, I suspect that the overall emissions from making games globally is the highest it's ever been. But we just don't know, and I'm hopeful that if they haven't yet will soon – they definitely could – begin to decline as emissions disclosures and net zero targets move from an optional extra to essential business practice expected by a variety of stakeholders.

Before I finish this already quite long post, I want to come back around to the point I started on – which is the prioritisation of mitigation over adaptation. We have the answers for mitigating many parts of the games industry’s footprint already – real reductions are so, so possible for most of the game making business. Emissions from Scope 1 and 2, from direct use of fossil fuels and purchased electricity, are positively, verifiably possible to reduce, even quite quickly. They can be capital or budget intensive, so getting buy-in from leadership is so critical (check out this blistering indictment). But we have the answers: solar power generation on buildings, power purchase agreements for those that can't, heat pumps for heating instead of gas, electric vehicle fleets, and purchasing guarantees of origin or other mechanisms for purchasing renewable electricity (I am planning some more writing about market-based solutions as well, so this space).

We even have the beginnings of some pathways and processes for reductions in scope 3 emissions – from Green Software and energy efficiency techniques, end-user energy measuring and reduction tools like the one Xbox launched, and organisations and alliances to start helping the industry with its supply chain emissions.

As Hannah Ritchie wrote earlier this year (she compiled the chart above on country-level emissions) – there’s no such thing as an “insignificant emitter”:

the world won’t tackle climate change if countries with ‘negligible’ emissions do nothing. Nor will it do this if big players… do nothing either.

She was talking about countries, not companies, but the same logic applies. If the games industry is even remotely close to the emissions of an entire country, our conclusions remain the same. As Ritchie takes pains to emphasise, this argument is aimed at the richest parts of the world which have been most responsible for emissions. That’s, by and large, where most of the games industry is.

Go read her article after this one, you won't be dissapointed. It’s really top-notch, just a super clear explanation. The bottom line for us is that every studio, every game dev is adding their little rock or pebble to the avalanche of global emissions, no matter how big or small, and we can’t brush that away. All emissions have got to go to zero.

Next time: we’ll look at the footprint of the distribution of games, and a few of the studies that have been done on distributing discs and digital downloads.

* NB: I used 5 tonnes per as the per-developer upper limit in the book for... some reason? I think maybe I was thinking of adding some extra padding for undisclosed scope 3. Or possibly the 2020 figures were revised after I wrote the chapter? I dont remember! It was the pandemic.