🌿 Green New Deal Simulator brings the 🔋✨vibes✨♻️ we need 🐸

Green New Deal Simulator is a free new game by Molleindustria – the art/games project by designer Paolo Pedercini (who also made Phone Story, Every Day the Same Dream, among other classics). It’s a lite deck-builder, in which the player takes on the role of a powerful government agency, tasked with choosing GND style initiatives from a deck, and playing them to specific regions of the US in order to bring CO2 emissions to zero, while also keeping unemployment in each region below a cap. If unemployment gets too high, no one necessarily riots, but you simply cannot play your policies anymore, and emissions remain as they are. Policies also have to fit within an available budget, and you can ‘skip’ a policy to advance time and partially refill this budget – but it means you miss out on the upside of playing the policy this time through the deck, and as you play (or skip) policies time advances towards the critical end of the game (which might be mentioned as being 2050, or maybe not). One policy (represented by one card) can also be placed in a ‘hold’ slot that lets you save it to play later if you don’t want to skip it or play it yet.

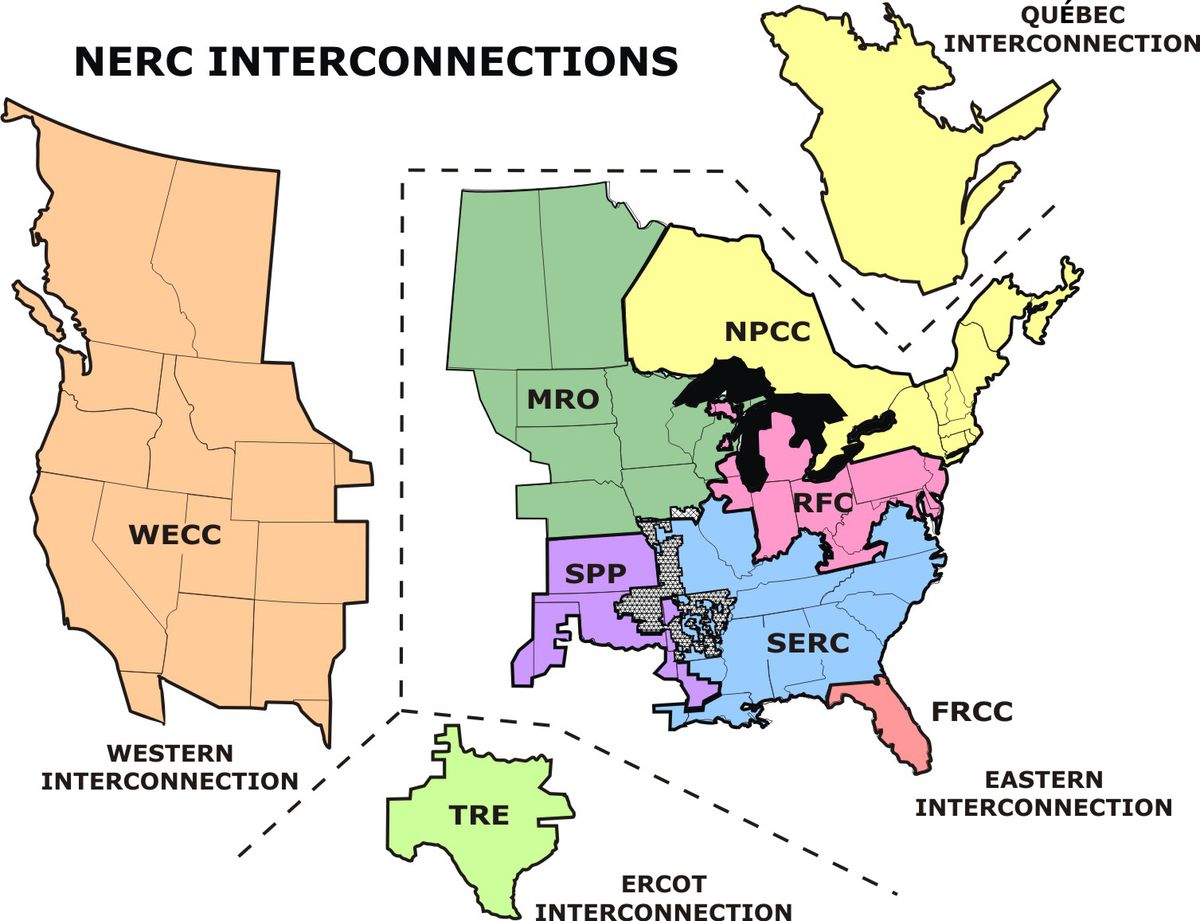

The other important aspect of it is the geographical map of the US, which is the playing field. On each region, roughly correlated to the major state in each region like ‘Texas’ or ‘California’, there is a pie chart that represents the current split of three critical measures: fossil fuel demand, fossil fuel power demand, and renewable power. Policies affect the balance of these three elements, and they behave in a pretty idiosyncratic way – while fossil power can be replaced with new-build renewables, fossil fuel demand has to be reduced before it can be displaced. Mastering this dynamic involves understanding how each of the policies affects the balance of these three elements and unemployment levels. Policies can affect not just the region they’re played in but also so called ‘fossil fuel producing regions’ as well, and the hard cap that is unemployment can prevent you from playing a good policy in one region if it threatens to surpass the unemployment cap in, say, the Appalachians or Texas.

In this way, GND simulator sets up a hugely fascinating possibility space that focusses our attention on aspects of the climate transition that are often rarely covered: public assent for policy, and macroeconomic indicators like unemployment. In an interview with Game Developer, Pedercini explains why he arrived at the particular balance of detail and abstraction he did:

The subject is complex, but you don’t have to tackle every aspect of it. The game focuses on a specific scenario/location (the USA), a specific timeframe (the next two decades or so), and a specific set of issues (like the tension between decarbonization and employment). It also puts the player in a very specific role (the secretary of a new, powerful department), so you only have a big picture view. You don’t even fix the environment, really, because ecosystem restoration and disaster mitigation are not part of the game.

I call this process of reduction “rhetorical scoping” or “ideological scoping”; it’s like defining the scope of a game but taking into account expressive and political concerns along with technical ones.

GND Simulator succeeds in ways that most climate games I’ve played rarely do. Even though I am on the record as saying I don’t believe content is enough to make make somethign a “green game” (as I stressed in both a journal article, then a chapter of my book, and in my GDC talk from 2022) I really appreciate this approach. As Pedercini notes in the same interview:

…it may be tempting to think that the more complex a game is, the closer it gets to the slice of reality it claims to portray. But to me, there is simply no way to approximate big socio-economic systems. All claims of realism are misguided or delusional. Realism is an aesthetic—complexity an aesthetic. Together they convey a sense of accuracy and objectivity, but it’s a vibe really, a preference in the great spectrum of gaming experiences. I’m making art (or propaganda if you prefer), and throughout my 20 years of game development, I always adopted cartoony graphics, meta humor, and satire to underscore how games are fundamentally opinionated, biased, and subjective. The term “simulator” in the title is ironic, as in Goat Simulator.

✨Vibes✨-based engagement with climate change is hugely underappreicated, and basically essential to getting people on board. In games, it's basically what I argue for in a different journal article (PDF here) and there are so many smart decisions in GND Simulator. The orientation to the subject through playful art and humour does take the edge off.

So I think it’s a triumph of a climate game – but I also think it’s maybe worthwhile to unpack some of the assumptions built into it. Because even though I think as a whole it works really well, for very good reasons there are some systemically important aspects left out. And some of those exclusions are pretty important.

The main thing that gets abstracted is anything like a detailed conception of the economic issues involved with the energy transition. The only two real econometrics we get are the GND budget itself (which has an inexorable logic of spending and replenishment) and a regional level of unemployment. These work fantastically well as puzzle elements, but they do preclude any real engagement with the politics of austerity, whether there is an assumed need for growth in the GND model of transition, or whether degrowth is possible (or necessary?) within GND and net zero frameworks. It also, I think implicitly, doesn't have room for thinking about alternative financing models, such as MMT, or even really the kind of Big Green Keynsianism that Adam Tooze writes about regularly. Keyne's famous phrase that "anything we can actually do we can actually afford" doesn't really come into the picture, perhaps for reasons of good game design, even though it's quite explititly Green New Deal proponents who argue for these sorts of massive, nearly unlimited spending programs. Of course, these are all issues a bit beyond the remit of the simple and effective “propaganda game” that GND Simulator is, but there’s still a need for these conversations! We should absolutely be involving the general public in them.

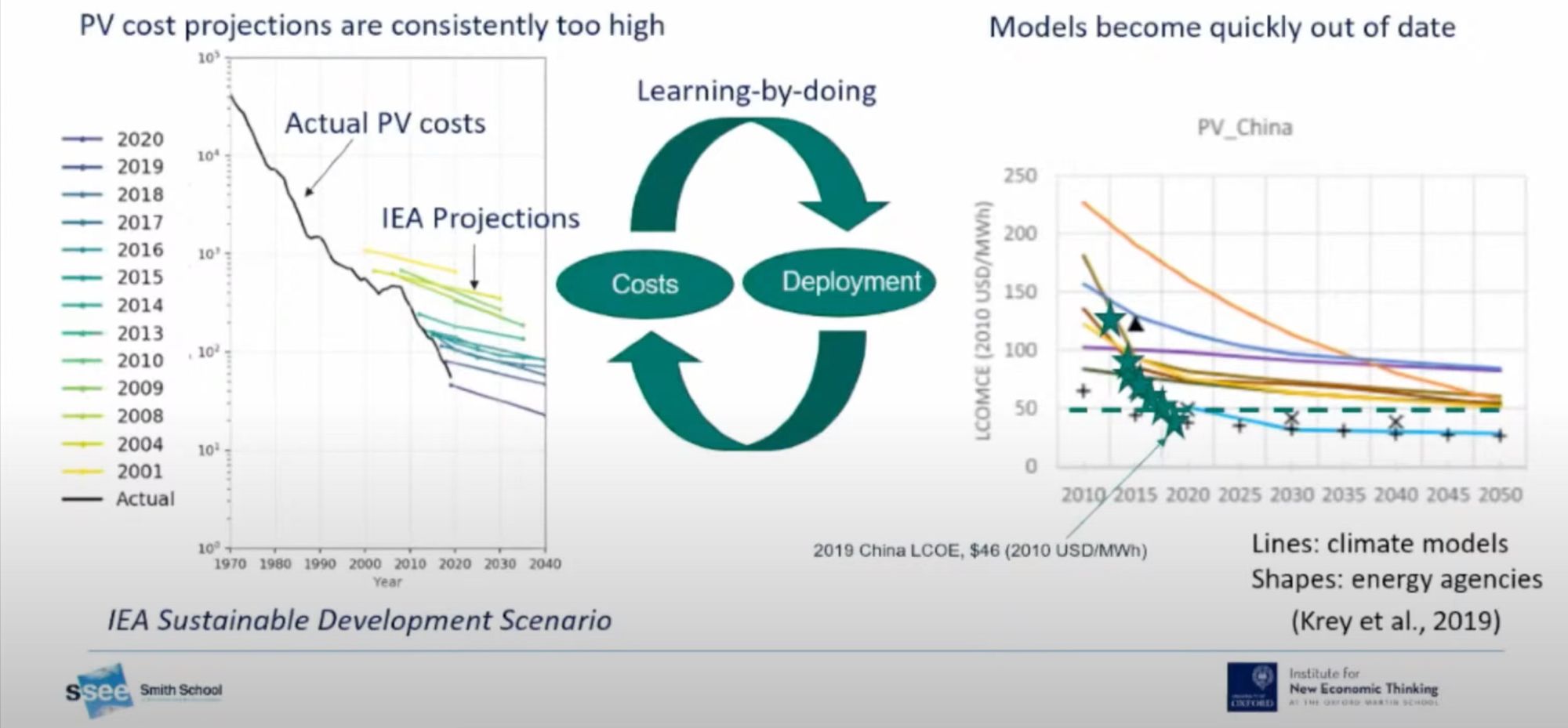

Other important economic dimensions to the energy transition that are excluded are the long downward trajectory of prices for new renewables. See this fantastic talk from a couple of years ago now that outlines a very persuasive set of reasons for why they keep falling in price, and why that trend is likely to persist for some time yet.

Here’s their slide with a series of frankly embarrasing graphs showing how far off every major price projection for renewables has been – they always underestimate and by huge margins. It’s one of the most hopeful rays of light in these often very taxing times.

Renewables are qualitatively different to other energy generation technologies – and the amount of research, development, and practical refinement from on-the-ground deployment means they are undergoing something like a revolution. In GND Simulator, you have to drop some serious cash from the budget to bring down the price of new solar and wind – even though with every new construction, knowledge and experience improves, the industry matures, and prices for the next one fall. That cycle is well and truly happening regardless of government spending on it, being primarily driven by the private sector and incredibly competitive Chinese solar manufacturers.

Similarly, the commitments of countries like the G7 and the goal of 100% renewable electricity by 2035 don’t really factor into the game either. These are real world political commitments that business and governments have committed to, and are expecting to be delivered. Markets and investors are pricing these in already, and publics are increasingly demanding action. The combination of multiple forces make these hard to back away from, even by reactionary governments. Of course, implementing any of these “trends” in a way that doesn’t undermine the game/puzzle would be a huge challenge, so it’s quite understandably absent. But to my mind it does leave the game with a certain feeling of ‘stasis’ or of being stuck in the present – like its perpetually the year 2023.

This also crops up in other ways. The set deck of policy cards are drawn entirely from the imaginary of the present, which I think is more of an actual missed opportunity than some of the others I've mentioned. It’s entirely possible to include some of the more way-out-there policy choices and ideas – especially as the climate chaos ramps up towards the deadline. I wanted to see some of the ones that Kim Stanley Robinson outlined in Ministry for the Future for instance. Re-wilding half of the land on earth, social movements that drive demand down though energy sobriety (aiming to use <11kwh a day!), and other currently speculative bets on what alternative, slower modes of travel will become necessary (airships and boats!). There just isn’t really room for these in the GND simulator, and maybe that's fair enough for a project of this scale.

Similarly, any sense of the consequences of real social unrest, or the impact of the revocation of the social licence to operate for fossil fuel producing companies and regions leaves it feeling a bit weird. Sure there will be holdouts and deniers right up to 2050 – especially if we succeed – but the mainstream legitimacy of fossil fuels is already waning. It never seems to here.

These are all key dynamics and drivers that I believe will be major drivers of our climate future for the next twenty to thirty years, and perhaps regrettably they can't be found in the GND simulator. Imagination can only carry us so far, because some of these systems simply can't be entirely abstracted from those facts-on-the-ground developments.

Those quibbles aside, there are some things the game does really well and its on these I want to concentrate, as they are what really make the game an artistic triumph. Firstly, it highlights the importance of geography and the real distinctions between places – Texas does not decarbonise in the same way as Washington state! Figuring out which policies work best for a place is actually both a compelling puzzle aspect, and I felt like the mental models I already had in place actually helped here. Case in point – when I won, I realised that I had reproduced the existing US energy grid, with the exception being that I had actually integrated Texas into the network. It just worked out better that way!

In any case GND Simulator concretises these vague notions in ways that I suspect are extremely helpful and productive. Probably it can only do that because of the level of abstraction, so you win some, you lose some.

The game also makes it makes it really painfully clear how difficult eliminating the last residual fossil fuel use is (or could be). On my first two tries I got to 90% renewables just about everywhere, with an integrated national energy grid with transmission lines across the entire continent, but I had neglected to make sure I eliminated the last bits of gas demand from every region, ran short of the right policies by the end. Is this a real world dynamic we can expect? I have no idea.

Certain solutions – like investment in public transport and subsidised electrification programs – both seemed to have diminishing returns. I think this is because there are policies that work by cutting a certain percentage of FF demand rather than absolute amounts. These start out as awesome policies initially when FF demand is high, but become less useful as it drops. Again, I'm unsure whether this reflects any real world dynamic, or if its just part of the puzzle aspect of the game. But it’s plausible, and made me think about the problem in a new light.

What it does replicate, by forcing the player into it, is the extremely important strategic approach of looking for the biggest reductions possible at any given time. Taken together with the stubbornness of residual FF demand, it points to a useful paradox: the necessity of big, fast cuts (like energy efficiency), and the likelihood that we will need to find absolute emissions reductions as well. These involve hard choices, like ending FF consumption somehow. Above it all floats the spectre of the far-fling soon-to-be unemployed Appalachian coal worker, who deserves our empathy and support.

In the end, I found Green New Deal Simultor incredibly encouraging and hopeful – and it does wonders to play around with how achievable much of the transition seems to be, with just a bit of planning. Maybe it’s a bit arbitrary in how it deploys solutions – like how much a new solar/wind farm displaces fossil power demand etc – but in terms of the sheer vibes? Unbeatable.

I give it 4 out of 5 IPCC reports.

Green New Deal Simulator rules. It’s free, it's on Steam as well as Itch, even playable in your browser.

It takes like 30mins – give it a go and show me your electricity maps.