How does a major content release affect sustainability?

Hey before we get into this week's post – remember the game industry Net Zero Snapshot I last did way back in 2023? Well, members of the Sustainable Games Alliance woke up this week to an early Christmas present! Dropping right into their inboxes is the new and improved SGA 2025 Game Industry Snapshot – with an abundance of new features, insights, analysis, and many old favourite benchmark metrics.

I’m particularly excited about the brand new game industry-specific Scope 3 category intensity metrics, which let companies see how they perform against the disclosures of the competition on things like corporate business travel, data centres, and even use of sold products (Scope 3.11 – actual gameplay). For now, it’s SGA member exclusive, so you know what to do if you want it. Join the Sustainable Games Alliance on our mission to make games as sustainable as can be.

Here’s a few highlights to whet your appetite.

I’ll be back in January with a couple more details, and to discuss the high-level takeaways, plus what I think it all means for the sustainability of the games industry going forward. The challenge is still ahead of us.

This week, I started thinking about what it means for game infrastructure when it needs to handle new content releases. I read a refreshingly candid interview at Aftermath, in which Warframe creative director Rebb Ford, was asked broadly about why game servers often go down when a big update happens. It’s the sort of background question that you’ve probably had yourself, and maybe, like me, you’ve unconsciously built a bit of a mental model to explain why it happens. Something like “the best online games with intricate online infrastructure are often the victims of their own success.” Launch days are rarely flawless. So I really appreciated this description of the team’s approach to prioritisation and just how many different systems and processes are involved in a game like Warframe – and the sheer amount of digital infrastructure:

In Warframe’s case, elements can function independently, but if they’re not all working in conjunction, players quickly begin to see the seams.

“A lot of people can be logged into the game, and that's cool, but if you can't play, then there's a problem,” said Ford. “It's like Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Can you chat? You don't need chat to play the game, but chat servers run independently. Those were hit the hardest on Old Peace launch day, and we fixed it fairly fast by spinning up more capacity."

I’ve experienced something like it many times over the years, with expansions and new context drops generating long wait times and shaky performance as servers creak and groan. It often exposes the seams in game worlds: I remember entire zones would go offline in some World of Warcraft expansions, kicking you to the login screen. New Destiny 2 seasons often meant errors kicking you back up to space in the same sort of way. Breakout hits often find themselves with server issues (a good problem to have), and a big burst of hype can brings players to check out new content in numbers that stretch servers, sometimes to breaking, before stability is achieved, players consume the main content, and then move on. Dealing with peak player numbers before they settle back into a more regular groove has become a familiar experience – and initially I thought this post was going to be about strategies to spinning up and down different server capacities. But before we even get to that, there’s something more fundamental that happens when new content drops.

Here’s the Steamdb player count chart for Destiny 2 over 2025, with the little two-letter markers corresponding with both peak player counts and new seasonal content drops. The peaks are a physical representation of player enthusiasm for the game and the exciting new opportunities that come with them.

But before anyone even plays the game, the first sustainability impact that a content update triggers is a download. Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of data tracking this, and as I’ve suggested before, I think this is an area that the industry has neglected a little bit. Digital downloads are low emissions, since internet infrastructure is getting very efficient at sending a lot of data around these days, but it’s still not yet zero emissions. So we should be tracking and optimising for this.

Earlier this year, we introduced the SGA Standard component for calculating downloads – or in the parlance of the Greenhouse Gas Protocol Scope 3.9 ‘Downstream transport and distribution’ emissions. I wrote about it back in July, and explained that the method and associated data input sheet (which I used to calculate most of the figures in the rest of this post) allow us to measure a pretty good estimate for the energy and emissions from game downloads.

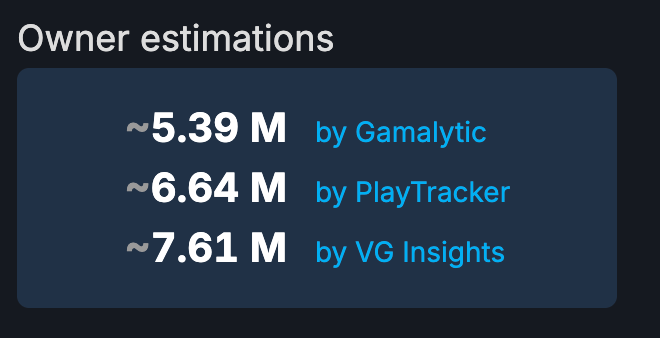

We can see what the method produces by looking at the most recent update to my current game obsession – Arc Raiders. This week, via a modest 13.3 GB update file, the game was updated to V1.7.0 (it may be a slightly different size for other languages, but let’s assume the difference is negligible for simplicity’s sake). The update brought a big new seasonal event, quests and more. The lowest estimate of the number of owners of copies of Arc Raiders on Steamdb is 5.39 million, and since the game is fairly new, let’s assume that at least 80% of players still have the game installed, which, if true, would mean about 4.24 million players received the update.

A digital download activates two physical systems we can estimate – the server that retrieves and sends the initial data from storage to the client, and the internet infrastructure that sits between the server and the end user. Let’s tackle the infrastructure first, because we have the most data about it. The most recently published research (from a few years ago now) put the typical figure for internet infrastructure energy consumption at 0.023 kWh of power consumed for every GB transferred. That’s research from Aslan et al (2018), and at the time they found that internet infrastructure energy consumption was (quite impressively) halving every year. But there’s also a lot of variability depending on where in the world the internet network actually is, with older hardware using more power to send the same amount of bits, and legacy infrastructure lagging the cutting edge in various places – so it’s all a bit complicated, well above my pay grade.

But, as I wrote about for the newsletter in July, if the internet intensity was still halving now, the amounts of energy involved would be infinitesimally small (by my calculations, just 0.000044921875 kWh/GB!), meanwhile the public disclosures of Australian and NZ internet data providers (and French ADEME databases) have not been keeping up with that same trajectory. Australia’s internet in 2024 had an average intensity of 0.00776 kWh/GB, and the French figure (which I suspect is ultra conservative) is around 0.208 kWh/GB if you calculate it (they disclose CO2 per GB figures, but you can get an approx figure by using the French grid emissions factor to work backwards). In any case, the real internet is not keeping up with previously observed trends.

So let’s use the Australian intensity figure since it’s the most recent real world observation. For 13.3 GB of data transferred, the Australian internet between my computer and the server is estimated to have used 0.103208 kWh, or 103.2 watt-hours. Doesn’t seem like that much, but now let’s multiply that by 4.24m players. If the rest of the world’s internet uses power at the same rate as Australia’s, that comes out to 454,115.2 kWh, which (applying a global average emissions factor of 473.13 gCO2e/kWh) gives us 214.86 tonnes of CO2 emissions just from one update. That’s the equivalent of just over 50 petrol-powered cars on the road for a year, or 497 barrels of oil consumed. The world’s internet might not be as efficient (or inefficient!) as Australia’s, so that number in reality will vary, but it’s a ballpark.

The other physical system that a download activates is the Steam servers themselves, which have to serve up that data to players. Here we are on sketchier ground, as Steam does not publish any information about its server energy consumption, or even its corporate footprint (nor do a lot of other platforms or services – though GOG.com does, appearing in CDProjektRED’s annual GHG disclosures. Thanks GOG!). Because we have no real data about servers, we have to estimate them, and whenever we estimate, we need to be conservative because it’s better to over-estimate than underestimate. (This is another reason to try and actually measure things directly; the numbers just come out lower.)

Steam pushes content to users via “edge networks” which cache a lot (though perhaps not all?) of Steam’s data and sit very close to players, often inside individual ISPs’ networks, so they are super-fast to download for players. But this might put them (to some degree) outside Steam’s immediate control. It’s not clear whether Steam has (or can get) this data about the intensity of its CDNs (content delivery networks), though, as a powerful player, I am certain they could make providers bend over backwards to provide it if they tried.

The most cutting-edge figure I have been able to find for a super-efficient CDN is this one from Varnish software , which announced in March 2024 having achieved 1.18 Gbps/Watt, which, when converted, gives 0.008 kWh/GB (you’ll just have to trust me on that one or figure out the maths yourself). The real-world CDNs in use by Steam today are probably not quite that efficient. But at least it’s a bottom-up figure measured from an actual server. The alternative approach, which I took for the SGA Standard, was a top-down one, where I used the total amount of data processed in all data centres as reported by Knight Frank and divided it by the total energy consumption in all data centres. This is clearly a crude method, but it might be closer to an average or worst-case scenario figure. This gives a much higher number – 0.277 kWh/GB, two orders of magnitude more energy than the cutting-edge Varnish measurement. So the reality is probably somewhere between these two.

If we estimate the possible ranges of CDN energy consumption using these high and low cases, we get energy consumption figures of as low as 451,136 kWh, or as high as 15,639,381 kWh. In terms of the emissions associated with those figures, that’s 213.4 tonnes of CO2e and 7,399 tCO2e, respectively (using the same global EF – so regional differences will matter in the real world).

Put it all together, and a single 13.3 GB update to 4.3 million players is potentially responsible for 428 tonnes of CO2e at the low end, or as much as 7,600 tonnes of CO2e at the high end. The larger figure is equivalent to 1,773 cars on the road for a year, or 0.02 natural gas power plants. (Though it’s almost certainly higher than reality, which I suspect will be closer to the smaller end – but we just don’t know until we actually start to measure it).

I promise I’m not trying to pick on Arc Raiders. In fact, this is a relatively small update, all things considered. There are so many even bigger games that do larger, or more frequent patches, for even larger player numbers. I remember quite clearly a Destiny 2 release that was a 100+ GB download – essentially redownloading the entire game. If we repeated the process and kept all things equal, we would see one or even two orders of magnitude higher emissions from downloads from that game, because the game files are that much bigger, player counts are higher, and so on.

So let’s talk about something positive about Arc Raiders. Last month, I wrote about the total emissions footprint of playing PC games as estimated via Steam data, and at the end of that post, I cheered at the appearance of an Eco Mode in the Arc Raiders menu screen. At the time I wrote that:

Unfortunately, at present, I think it’s either implemented its settings at too high a level to make a difference for all but a very small portion of players with super high-end PCs, or it's not working as expected. In my testing and over about 60 hours of play, I have not once come back to a menu screen in a visible eco mode state.

I was able to get in touch with a team member (Gabor S.) at Embark this week, who also happened to be the one who introduced the idea of implementing menu eco modes in both The Finals and Arc Raiders. Gabor told me that yes, it wasn’t quite working as intended, but thankfully, this was detected recently and should be working properly in the live game now. The story goes that, very late in production, it was identified that the eco mode timer was kicking in during cut scenes and reducing the frame rate at a time when you obviously don’t want it to. So that was prevented, but as an unintended consequence, it meant that sometimes the eco mode timer wasn’t kicking in again once the cutscenes were over. Which explained why I wasn’t seeing an FPS drop in menus last time. I’ve checked it now and can confirm that yes indeed, it is now working as intended, and saving players who walk away from their games from wasting unnecessary energy, heat, and money on their power bills. The low FPS mode now kicks in after a mere 30 seconds of inactivity (great!), and as soon as the player gets back, it returns to full 60FPS.

So how much could this option save? I decided to break out the power meter to test how much of an impact it actually has (and that it was working) – and the results were surprising.

Based on some past testing, I expected that my PC was on the low-end of the hardware spectrum – it’s only a RTX 4060 and a Ryzen 5 3600, and I was expecting about 200-250 watts (equivalent to a PS5). But as soon as I got to the menu screen for Arc Raiders, for the first 30 seconds at least, it sat around 470-480 watts. That’s a lot of power. But then, something magical happened.

After 30 seconds, the FPS limiter kicked in, and the game dropped to 30 FPS. The power reading dropped too, to 320-330 watts, shaving around 150 watts off the total. That is a saving of about 32% – the same amount identified from the original Epic eco mode white paper. Based on Fortnite player behaviour, that translated into a 9% overall energy consumption drop across the entire player base. Compelling stuff! What a saving!

With a wiggle of the mouse, we’re back to 60 FPS and the 470-480 watt range, verifying that, yes, it is indeed the eco mode kicking in that is saving the power, and not some other background process coincidentally ending at the same time.

Since its release at the end of October, I’ve played 96 hours of Arc Raiders, and I imagine I could quite easily sink another 100 hours into it in the future. Many will play even more, I’m sure. If I spend 5% of my time AFK between matches, that’s 5 hours of wasted power. At full power, that’s 470 watts x 5 hours = 2.35 kWh of wasted power. If the idle state kicks in and reduces that waste by 150 watts, that’s saving me (and the same for everyone else who plays for another 100 hours) 0.75 kilowatt hours. 0.750 kWh x 4.3 million potential players is 3.18 million kWh, or avoided emissions of as much as 1,500 tonnes! That is more emissions avoided than the total from the game update we calculated earlier. And if players play for longer, or spend more than 5% of their time AFK, then crank that number even more.

This is the stuff that gets me out of bed in the morning. And in a way, it’s another lens on the same question of ‘how does a game release affect sustainability?’ In this case, it means the unintended consequences of the mad dash to release, as well as the potential to find and fix them afterwards. It’s the dual nature of the challenges of the frantic pace of modern game development and the opportunities presented by the constantly evolving modern video game.

On PC, especially, it means the ability to avoid a massive chunk of emissions with a tiny bit of effort. It’s a question that interfaces with the sheer complexity of modern videogame making – an endeavour which operates at or near the pinnacle of modern software engineering, efficient hardware deployment, and that spans the awesome length of globally connected internet infrastructure (submarine cables! light speed communication!) as well as international business partnerships – all elements tested by the enthusiasm of millions of simultaneous players.

Which brings us back to the Aftermath/Warframe piece where we started. Matching the demand to the enthusiasm of players is not free – it comes with costs:

”We still feel very young and scrappy, and we're like 'Can we even afford $600 more per month in capacity?'” she said. “That's the kind of question we ask ourselves on launch day. And then we're like 'Just do it! Just do it!'"

Warframe’s servers weren’t quite able to withstand the sheer weight of years’ worth of anticipation on launch day, but Ford was relieved that they didn’t go down for “hours and hours,” which would’ve necessitated a suitably less jubilant speech at the launch event in LA.“

We understand the financial costs a bit better these days – are even keenly aware of it, in the current budget-constrained environment – but we are still just getting started understanding the environmental costs. We will probably never pose the question in exactly the same way as the above quote – I doubt it will ever look like asking ourselves whether we can afford “600 kg of extra emissions” in the same way as we do with asking about extra financial cost, but whatever form it does take, I think we are not far from seeing it.

Thanks for reading Greening the Games Industry, and I hope you have a very restful and rejuvenating holiday and end to the year. I suspect this is my last (long) post for the year – thanks for coming along for the ride.