What’s the biggest bang-for-your-buck GHG reduction in games – and how do we find out?

One of the perennial challenges for those of us working on decarbonisation in the games industry has been getting a clear and complete big-picture view of the impacts games have on the planet. Without that, we have had to rely on guesswork and the experience of other industries, which can be a good guide but is still no substitute for actually knowing. So for the past few years, I’ve been trying to flesh out the picture of the footprints associated with different parts of the games industry – and have only been partially successful.

There are lots of reasons for that, but one of them has simply been the complexity and opacity of the industry itself. How is it structured as a production process? Is it the same in each country, for each gaming platform or for each type of genre? What business relationships are mobilised to facilitate games in 2025? What essential dependencies are there for certain types of infrastructure? What logistics chains are enrolled in the process, and in which parts of the world? There have been attempts made before to study the production process of individual companies, even from inside those companies, as well as to account for the practices of noncommercial game production as well. We have also seen publications from sustainability researchers inside the games industry that have helped to shed light on bits of the picture, but things change over time, and quickly in the games industry.

A lot of these questions and studies are, in one way or another, about the nature of the video game industry’s value chain – the network of work teams, relationships, products, tools, markets and communications channels necessary for shipping a game in 2025 and getting it played by customers.

As part of its vision for a sustainable Europe, the EU has embedded within the CSRD/ESRS disclosure process the requirement to analyse or map a disclosing company's value chain. This will, in the long run, greatly aid our understanding of where to target sustainability interventions by increasing transparency and visibility, and by helping us answer these types of questions above. To help get game companies started on that mapping process, I’ve tried to draft as “generic” a game industry value chain as possible and wrote a little explanation for the mapping process for the SGA ESRS Roadmap.

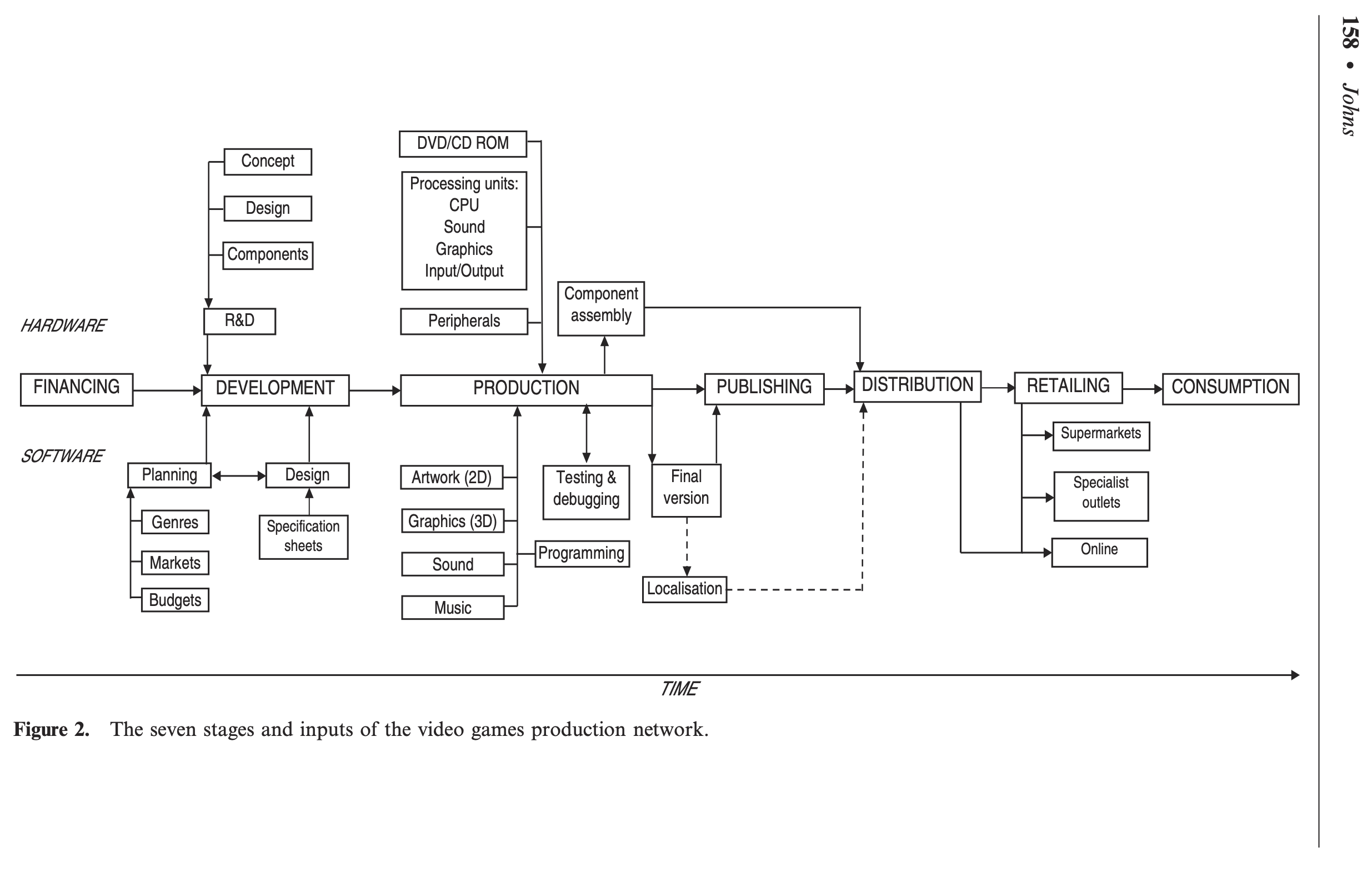

To do that, I returned to the game production process diagram that informed the research for my book. There, I drew on a foundational article by Jennifer Johns (2006) with the catchy title “Video games production networks: value capture, power relations and embeddedness”. Here’s the model Johns proposed almost twenty years ago (!!) – the result of more than a dozen interviews across seven countries.

Considering the year of the work and the relative immaturity of the industry compared to today, I still think it’s a remarkable attempt that captures a lot of important details we can easily overlook. But there are also anachronistic elements as well – can anyone imagine Supermarkets as a games retailing outlet anymore? Japanese Konbini’s might be the only ones? – and Johns could never have predicted the shape the industry would take.

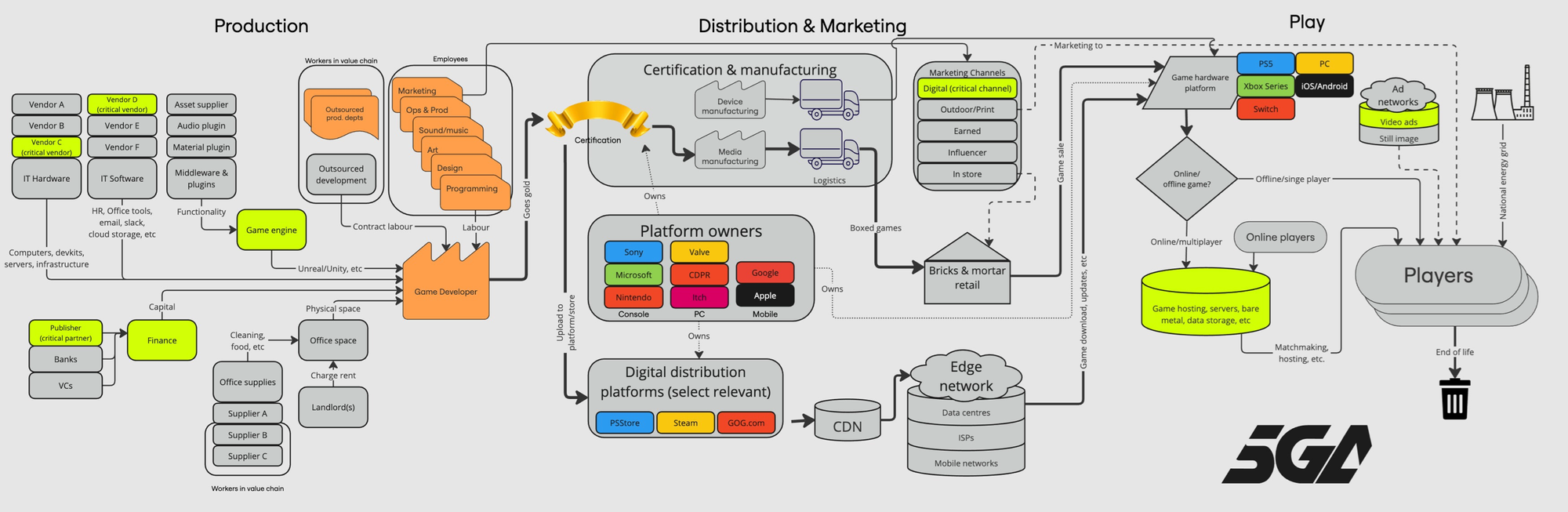

So I’ve tried to adapt it and revise the Johns (2006) model for 2025. It’s embedded here as a static image, or you can open it as an interactive Miro board and zoom around it to your heart’s content.

A couple of notes on it and its limitations. I removed the “hardware/software” division that Johns introduced. I think it made sense during the early 00s where hardware was still such a defining feature, but now that we are in the “everything is an Xbox” era I’m not sure that it makes as essential of a distinction. I’ve also simplified it down to just three stages – production, distribution & marketing, and play. There is still of course a hardware component to the modern-day videogame value chain, but my suspicion is that it is more about platforms and the (somewhat?) captive audiences on each that are the more essential features – not so much things like memory bandwidths, or clock speeds, etc. In any case, we could expand out the rhombus of the “Game Hardware Platform” with an equally complex value chain of design, raw materials, chip manufacturing, assembly, transportation… and whatever else!

Perhaps that’s something for future iterations. But that’s also something that you can help with. I would love to hear from you – dear reader – with your ideas for things the map above might be leaving out?

Does it reflect the picture within your organisation? What else could we add that is a source of value in game production that I’ve not though of yet? Try to keep in mind that, as a template, it needs to remain agnostic about specific companies, software, and suppliers. What categories of businesses, software, or relationships are absent here? What other key value producing elements of game production are there? Should there be a specific AI component, and the super long chains of data centre infrastructure, training materials, etc also belong on the map? Looking at it again now, I wonder whether live service games are adequately captured in this (certainly, there's no revenue flow back from players to the working capital for development which might be important for some types of game).

The goal for the tool (if you read the instructions on the Miro board version) is that individual disclosers at companies can take this as a basis to start from, add their own real suppliers, engines, plugins, work groups, departments, platforms, etc. and rename the components to their specific ones. This can then become part of their reporting, and eventually, inform our understanding of the key essential elements of the game industry value chain. This might finally start to give us some confidence to be able to say “Start here on your decarbonisation journey”. It certainly wouldn't hurt at any rate.

The modern game industry value chain has changed a fair bit since the early 2000s – it’s grown bigger, and more complex, with elements now totally essential to game production that would have been nearly unthinkable twenty years ago. Who could have predicted that a major part of the games market would become games that are free to play, and supported by ad revenue, or in-game transactions, for instance? The first iPhone itself wouldn’t even launch until the year after Johns’ (2006) paper.

Ultimately, production in 2025 is quite a similar process to 2006, in that it still involves the same times of inputs (labour, software, hardware) and still involves some kind of distribution to reach customers – even as those paths have drastically changed, and will likely change further. Hopefully, those changes can be made in ways that bring us closer to a sustainable games industry.

Thanks again for reading Greening the Games Industry. If you get some value out of the value chain map, please let me know. And if you’re still considering getting on board with the SGA , please reach out and we can have a chat about it.

We're now open to any games business or organisation that derives a substantial part of their revenue from games – so it's not just for developers anymore. Service providers too can join the Sustainable Games Alliance. We have got tons of work to do and we need everyone’s input.